Should Anyone Accused of a Crime Lose His Second Amendment Rights?

The New York Times complains that Robert Dear owned guns despite "run-ins with the law."

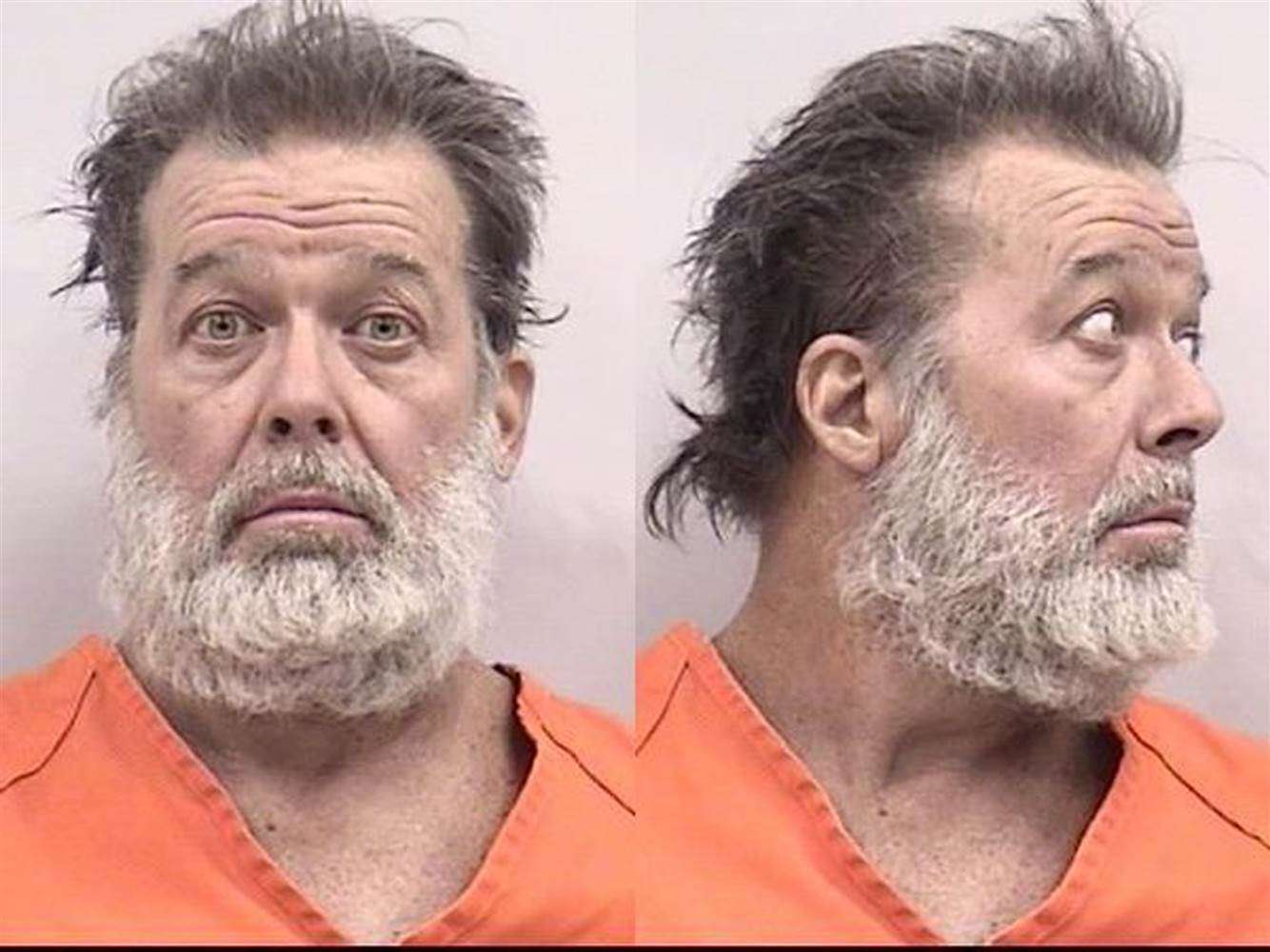

The New York Times reports that two ex-wives of Robert Dear, the man accused of killing three people and wounding nine others at a Colorado Springs shopping center last week, said he physically abused them, although no criminal charges were filed as a result. Dear was also once accused of raping a woman at knifepoint, although the charge was dropped after a witness declined to testify. (He claimed the sex was consensual.) The Times previously reported that another woman had accused Dear of hiding in the bushes outside her house so he could spy on her through a window, a charge that also was dropped. Since none of these allegations resulted in convictions, it still seems that Dear did not have the sort of criminal record that would have disqualified him from buying a gun: a current felony indictment, a felony conviction, or a domestic violence conviction, including misdemeanors.

Gun control supporters may argue that the reports of violence nevertheless should have marked Dear as one of those "people who have no business" owning guns, as President Obama put it on Saturday. That sounds plausible (especially in retrospect), but translating that view into law raises obvious due process problems. Does a mere accusation, whether in the form of a criminal charge, a police report, or a statement made during divorce proceedings, justify permanently depriving someone of his Second Amendment rights? Given the potential for false accusations, such a policy would inevitably affect many innocent people.

The problem is similar to the one raised by proposals to ban gun ownership by anyone on the FBI's so-called Terrorist Watchlist. Keeping guns away from terrorists sounds like a good idea, but merely appearing on the FBI's list, which may result from unjustified suspicions or guilt by association, does not make someone a terrorist. Likewise, being accused of rape or domestic abuse does not make someone a rapist or a wife beater, even if Dear's most recent arrest makes us inclined to believe those earlier charges.

A recent New York Times editorial complains that "Mr. Dear had several run-ins with the law and still had plenty of weapons at hand." The Times suggests "expanding the categories of people deemed too dangerous to have guns." But why should "run-ins with the law," including charges that are never proven, be enough to strip someone of the right to keep and bear arms? It is hard to imagine the Times endorsing that approach to any other constitutional right.

Show Comments (93)