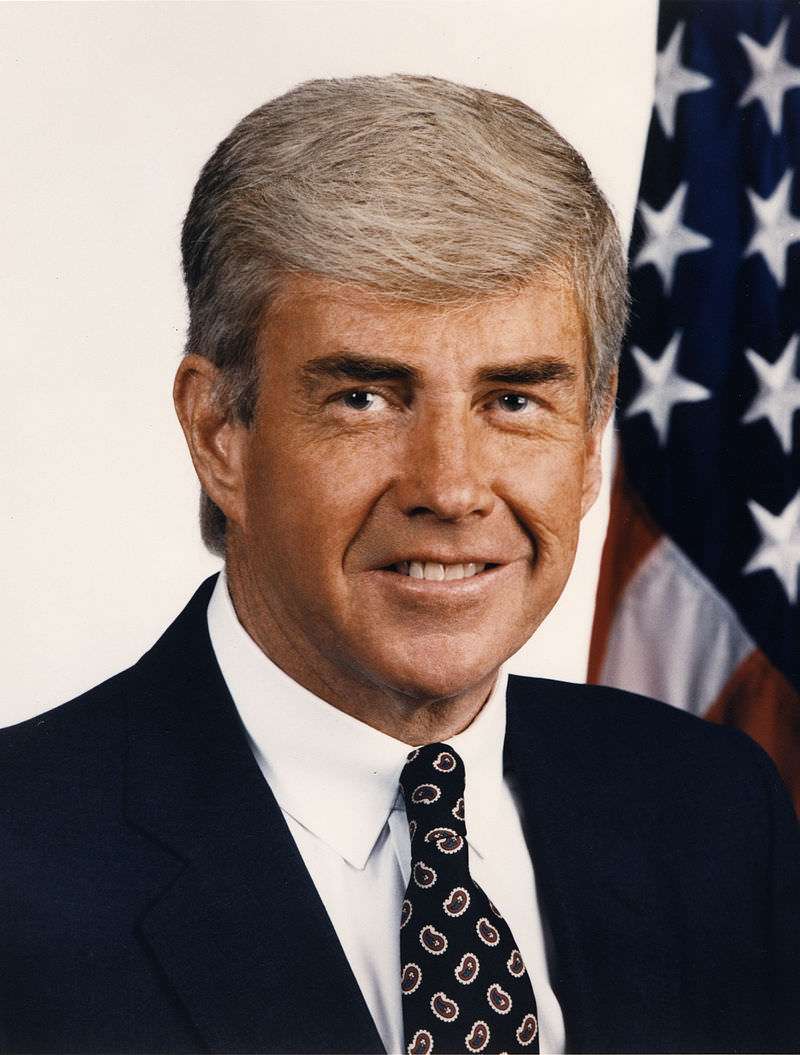

2016 GOP Candidates Could Learn Something From 'Bleeding Heart Conservative' Jack Kemp

They don't make Republicans like Jack Kemp anymore.

Just in time for the Republican presidential primary season—and for the free-for-all search for a new speaker of the House—comes a new biography of Jack Kemp. Jack Kemp: The Bleeding Heart Conservative Who Changed America, by Morton Kondracke and Fred Barnes, tells the story of a man the authors claim was the most important politician of the 20th century who was not president—a man, they say, whose sprit and policy ideas "could again help the country turn around."

It's an illuminating read. The authors quote Vin Weber, the congressman from Minnesota who is now a Washington lobbyist, describing Newt Gingrich's distinction between "magnet issues" and "wedge issues." Magnet issues attracted followers. Wedge issues divided Republicans from Democrats.

Said Weber: "There was no such thing as a wedge issue in Jack Kemp's vocabulary. Everything was a magnet issue."

One of Kemp's projects was to attract more blacks, Jews, and immigrants to the Republican camp. The authors trace his attitude on race to his time as a pro football quarterback in the early 1960s with a lot of black teammates. He told team management that it was unacceptable for black and white players to be housed in separate hotels, or to be assigned roommates based on race. Later, as a congressman, he supported voting rights for the District of Columbia and a federal holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.

Kemp attended Fairfax High School in Los Angeles at a time when it was heavily Jewish. As a congressman, Kemp outflanked the Reagan administration on the pro-Israel side, opposing a big arms sale to Saudi Arabia and supporting Israel's preemptive attack on an Iraqi nuclear facility, an action the Reagan administration condemned. He was prone to quoting Maimonides on the campaign trail, occasionally frustrating his campaign staff in Iowa and New Hampshire. And he was a prominent advocate for Jews who were denied the right to leave the Soviet Union.

On immigration to America, Kemp consistently favored liberalization, including a path to citizenship for illegals. He criticized a Republican proposal for a wall along the Mexican border as "a prescription for electoral and political disaster" akin to Barry Goldwater's 1964 vote against the Civil Rights Act.

The book argues that Kemp's greatest significance was not his inclusive style but rather his championing of pro-growth tax-cutting during the Reagan presidency. There the most fascinating part of the story is the role played by another former professional athlete, Bill Bradley, a Democrat senator from New Jersey who used to play for the New York Knicks.

Kondracke and Barnes report that Bradley read Milton Friedman and that he disliked the tax code because of "the gyrations he and other athletes went through to avoid taxes."

In August of 1982, Bradley and, of all people, Rep. Richard Gephardt introduced a bill reducing the number of tax brackets to three from 14 and reducing the top rate to 30 percent from 50 percent. The Democratic presidential candidate, Walter Mondale, rejected the plan. Then came a poolside dinner at Jack Kemp's house in Bethesda, Maryland, where the writer and policy intellectual Irving Kristol "stunned the group by suggesting Republicans simply adopt and cosponsor Bradley-Gephardt."

The book says Kemp and Bradley, as the "leading proponents" of tax reform, "made numerous joint appearances—not acting as rivals, but as collaborators."

Democratic involvement wasn't totally unexpected; the Reagan tax cuts were modeled on President Kennedy's, as this book makes clear. It quotes Kemp aide Bruce Bartlett as recalling Kemp telling him, "We keep talking all the time about the Kennedy tax cut. Why don't we just replicate it? Let's get rid of all this baggage and just do a clean, straight, duplication of the Kennedy tax cut."

What part of the Kemp agenda remains to be implemented? There's a monetary policy piece of it; the congressman was an advocate of a return to a gold standard, or at least changes to the Federal Reserve. There's an anti-poverty piece of it; Kemp, who served as secretary of housing and urban development in the George H.W. Bush administration, favored both school vouchers and Margaret Thatcher-style privatization of public housing projects. Immigration reform is yet undone. On the tax issue, Kemp wanted a 19 percent flat rate on income while retaining the charitable and mortgage interest deductions.

Kemp's legacy is not only ideas but also people. Paul Ryan, now the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and a possible speaker, was, early in his career, an assistant to Kemp at the advocacy group Empower America. The question that lingers, though, is where are the Democrats of today to play the roles of John Kennedy or Bill Bradley? If there's a hope that Kemp's ideas will again help turn the country around, it may depend on them finding at least a few allies outside the confines of the Republican Party.

Show Comments (32)