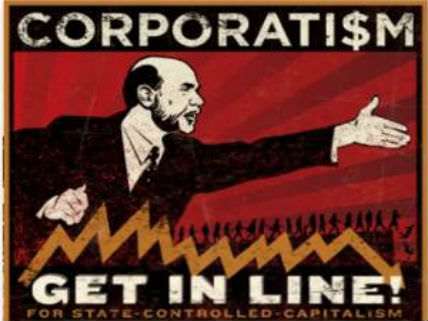

Crony Capitalists and Special Interests Dragging Down U.S. Economic Growth

Washington Post columnist Robert Samuelson makes the case.

Unemployment is now at 5.1 percent, yet American wages and incomes are stagnant. Why is this happening? In an insightful column in today's Washington Post, Robert Samuelson suggests an explanation based on the work of economist Mancur Olson, As I have explained earlier public choice theorist, Mancur Olson, argued in The Rise and Decline of Nations (1982) that economic stagnation and even decline set in when powerful special-interest lobbies—crony capitalists if you will—capture a country's regulatory system and use it to block competitors, making the economy ever less efficient. The growing burden of regulation could some day even turn economic growth negative.

Samuelson notes that wage increases have histroically tracked increases in economic productivity. Last year productivity increased by only 0.5 percent. This contrasts with a late 20th century rate averaging about 2 percent per year. Samuelson then turns to Olson for a possible explanation for the slow-down in productivity: the proliferation of regulations adopted to protect special interests. From Samuelson:

Although an economist, Olson revolutionized thinking about the political power of interest groups. Until Olson, conventional wisdom held that large groups were more powerful than small groups in pursuing their self-interest — say, a government subsidy, tax preference or a protective tariff. Bigness conveyed power.

Just the opposite, Olson said in his 1965 book "The Logic of Collective Action." With so many people in the large group, the benefits of collective action were often spread so thinly that no individual had much of an incentive to become politically active. The tendency was to "let George do it," but George had no incentive either. By contrast, the members of smaller groups often could see the benefits of their collective action directly. They were motivated to organize and to pursue their self-interest aggressively.

Here's an example: A company and its workers lobby for import protection, which saves jobs and raises prices and profits. But consumers — who pay the higher prices — don't create a counter-lobby, because it's too much trouble and the higher prices are diluted among many individual consumers. Gains are concentrated, losses dispersed.

The dilemma for democracies is clear. Voters expect governments to cater to their needs and wants — and one person's special interest is another's way of life or moral crusade. But if governments cater too aggressively to interest groups, they may undermine (or have already done so) the gains in productivity and economic growth that voters also expect.

So this is another possible explanation for the productivity slowdown, which afflicts many advanced countries. These societies are riddled with programs and policies promoted by various interest groups that "can increase the income [of the groups' members] while reducing society's." If he were alive today, Olson might well add that higher psychic income — the feeling of "doing good" — also motivates many interest groups.

It may be even worse than Samuelson thinks. The burden of regulation may have so reduced economic growth over the past 7 decades that Americans are 75 percent poorer than they would otherwise have been, according to economists John Dawson of Appalachian State University and John Seater of North Carolina State.

For a somewhat more hopeful analysis see my article, "Is U.S. Economic Growth OVer?"

Show Comments (94)