Malthusians v. Cornucopians, a more critical review of The End of Doom

Bailey responds to the criticism below

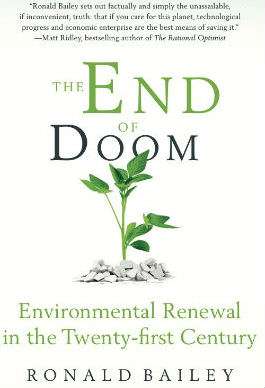

I am cross-posting various reviews from over at RealClearBooks of my new book, The End of Doom: Environmental Renewal in the Twenty-first Century (St. Martin's Press) as a convenience for Reason readers (and a mild effort at self-promotion). This next one is a bit more critical of the book. I respond to the criticisms below.

Malthusians v. Cornucopians

Reading Ronald Bailey's The End of Doom, I was reminded that the debate between prophets of a looming apocalypse and self-styled cornucopians has a long history, the modern version of which can be traced to the writings of Thomas Malthus in the eighteenth century warning that humanity's ability to reproduce would outstrip its ability to feed itself. The twentieth century saw no shortage of neo-Malthusians, countered by those—such as Julian Simon, Bjorn Lomborg, Gregg Easterbrook, and Bailey himself—with a far more optimistic vision for humanity's future. By now the combatants know their roles and lines too well. The debate has gotten pretty stale.

It's not that Bailey's argument is totally off-base. In fact, I'm skeptical, too, about warnings of apocalypse around the corner and sympathetic to visions of a bright future for people and the planet in the twenty-first century. But securing that future is by no means simple or guaranteed.

In The End of Doom, Bailey takes on a series of issues that he believes have been vastly misunderstood by the neo-Malthusians and their fellow travelers: population, peak oil (and peak commodities more generally), the precautionary principle, worries about a cancer epidemic, genetic modification in agriculture, climate change, and species loss. For each, the argument is much the same. Concern is overhyped. Technology driven by "free markets" has always provided solutions and will do so in the future as well. But Bailey's analysis never really gets beyond the cornucopian arguments that have been advanced many times before.

To take one example, Bailey accurately finds that the predictions about a "population bomb" advanced in the 1960s and 1970s were wildly wrong. Advocates like Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren—currently President Obama's science advisor—warned of a global crisis that might require draconian action such as forced sterilization. History has proved these arguments ridiculous and even unethical. Yet, as Bailey shows, latter-day Malthusians are saying the same things.

But Bailey stands on shakier ground when he argues that the "population bomb" was diffused because of the so-called Green Revolution, which brought high-yielding wheat and other crops to India and elsewhere. Bailey asserts that Norman Borlaug, popularly known as the father of the Green Revolution, "is the man who saved more lives than anyone else in history" through "a massive campaign to ship the miracle wheat to Pakistan and India." In Bailey's view, the "massive campaign" arrived just in time to prevent the famine predicted by Ehrlich.

It's a great story, but it's wrong.

A more accurate history shows that the specter of a looming famine in India was an invention engineered by President Lyndon Johnson to help sustain the U.S. Food for Peace program, which faced a politically skeptical Congress. Technological advances had led to a glut of crops in the U.S., low prices for commodities, and unhappy farmers. Agricultural aid was also seen as a useful strategy in the Cold War. So Johnson wanted the shipments made. Thus, as historian Nick Cullather writes in The Hungry World, "through the fall of 1965 [LBJ] developed the theme of a world food crisis brought on by runaway population growth."

In fact, official State Department notes reveal that when Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi visited Washington in spring 1966, one of her agenda items was to get the story straight about a crisis that didn't exist. The Indian delegation noted that, "The situation in the United States is that to get a response, the need must be somewhat overplayed." Scientists and the media jumped on the bandwagon, and a mythology of famine was born.

Bailey's restatement of the Green Revolution mythology in fact gives neo-Malthusians far too much credit, suggesting that they were correct in their forecast of global famine, only to be proven wrong by the wonders of technological and market innovation. In fact, the neo-Malthusians were never right to begin with. Bailey is promoting a solution to a problem that never existed in the first place.

In 2003, the International Food Policy Research Institute asked what would have happened if the Green Revolution in the developing world never happened. They concluded that developed countries would have produced more and trade patterns would have evolved differently, but the situation "probably would not be considered a 'World Food Crisis.'"

Perhaps ironically, it seems that the cornucopians need the neo-Malthusians to be correct in their diagnosis of potential apocalypse so that they can argue that their preferred solutions provide answers. But what if both sides are wrong in significant respects? Is there room in our debates for a third perspective?

It's easy to see the end of the world in every technological innovation. It is just as easy to look at the generally improving state of the world and conclude that things will always continue to improve, and that when problems do arise, they will be easily solved.

Our public debates over economics, technology, and political power deserve better than a tired rehashing of Neo-Malthusianism v. cornucopianism. And yet, these polarities remain appealing to many. Bailey recounts a conversation he had with his editor back in 1992, when he brought an earlier version of these arguments to him. His editor said that he'd publish the book, but "if you'd brought me a book predicting the end of the world, I could have made you a rich man."

The "end of doom"? Hardly. The end of Panglossian optimism? Nope, not that either. The dance of the two will no doubt go on.

Roger Pielke Jr., is a professor at the Center for Science & Technology Policy Research at the University of Colorado – Boulder.

Author Ronald Bailey Responds

First, I want to thank all three reviewers for taking the time and spending the intellectual energy to engage seriously with my new book. In general, I think that both Darwall and Easterbrook fairly characterize and explain its contents and goals. Pielke has some reservations.

For the most part, Pielke agrees with me, admitting that he is "quite sympathetic to critiques of apocalypse around the corner." He is impatient with my chronicling of environmentalist doomsaying over the past several decades, but he should remember that the more than 200 million of his fellow citizens who are younger than he is (46) do not know the sorry ideological history of Neo-Malthusianism. As philosopher George Santayana reminded us, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." By reminding readers of the past, I hope to spare future generations from being duped by doom dogmas. I suspect that even Pielke would agree that that is a worthy aim.

Pielke further objects that I give Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution too much credit for forestalling the world-spanning famines widely predicted to occur in the 1970s. It bears noting that in 1970, the chairman of the Nobel committee explained why it had chosen Mr. Borlaug for its Peace Prize in this way: "More than any other single person of this age, [he] has helped to provide bread for a hungry world." With regard to Nick Cullather's historical revisionism: Revisionists must revise. That's what they do. By the way, India's wheat harvest jumped 45 percent in 1968.

I certainly agree with Pielke that securing a "bright future for people and the planet" is "by no means simple or guaranteed." I do explain in some detail how the technological progress and wealth generated by democratic free-market capitalism makes environmental renewal in this century possible. While Pielke strikes a world-weary pose of intellectual ennui over a supposedly "stale" debate, he oddly fails to mention that there is between me and the Neo-Malthusians one big difference: My predictions have consistently proven right and theirs wrong.

Ronald Bailey is the author of "The End of Doom"

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The conscience of a liberal:

http://www.seattletimes.com/se.....beach-lot/

Government owns everything (property taxes are just rent) and we peons should be grateful that they allow us to use their land, even if for a few years until someone more important needs it. Know your place, peasant.

Shoosh. the scam only works if the marks don't know about it.

RC Dean will tell you that property is merely a privilege bestowed by the sovereign.

Not to defend Murray, but the proposed use is a public beach access that until recently was being used by the public to access the beach. At least it wouldn't go to a crony developer.

Personally, I would counter-offer the city saying we will accept the cash but on the condition that there will be no parking of cars anywhere near the access. Make Mr. Bicycle Lane eat shit by rendering the access inaccessible or risk pissing off Mother Earth.

Unfortunately, the city tried to fight them in court and lost. So now the city's pulling this. Makes one wonder why they bothered with court?

The whole thing got kicked off by a technicality of paperwork in the 1930s.

Honestly, if I were a property owner, I'd had avoided the legal battle by retaining ownership of the property, but allowing the public access through the beach. Because I've got nothing but the milk of human kindness in me.

I'm wayyyyyy late to this party, but cities use eminent domain, declare something public and then sell it back into private hands all the time. This is an example.

Also, I also have to admit that at least the eminent domain is for actual public use, instead of "public purpose" which is a euphemism for "wealth transfer to one of my campaign contributors".

Unless there's something I'm missing, the gov can always turn around and sell public property back to private investors, no?

The currently intended use of the property does not preclude government officials from changing their minds later on.

There's nothing you're missing.

I just looked on Google maps and it looks like there is a path leading down to the lake on lot over. And there doesn't seem to be any public access in that area, anyway. I do not understand.

Wow. Alternate headline: Mayor destroys millions in property value for homeowners on private lake.

Public access will mean every lot on that lake will plummet in value. Washington state has some of the highest property taxes in the nation. This is what they are paying for - a good, hard fucking.

"on private lake"

In no universe is Lake Washington in Washington State a private lake.

Not that that would be a bad idea...but legally politically, historically nautically culturally and geographically it just simply is a public body of water and has been for about 10,000 years.

$400K?

Offer $4M and be done with it.

I read somewhere that Bailey published something.

Ronald Bailey sure is one shamelessly self-promoting whore, isn't he?

You know who else was/is a shamelessly self-promoting whore?

Sandra Fluke?

Nonstopdrivel?

Episiarch's mom?

Since Trump hasn't yet been mentioned in the comments, I'm going to go with Carly Fiorina

You know who else is a shamelessly self-demoting whore?

Nonstopdrivel?

Dammit, man.

The mattress girl at Columbia?

Joe Bonamassa?

I mean, seriously, do not sign up for his email updates, you will get one approximately every eighteen minutes.

Yeah, publishing criticism of your work is totally shameless.

I am more referring to the frequency of publishing. Three articles in less than two days? Certainly appropriate for his own website. I don't see how this is the venue for that.

If he doesn't promote himself, who will?

Your mom?

She can try, but as far as I know she has no contacts in the book world.

Stop being so fucking serious. It's Friday for fuck's sake!

*checks calendar*

You appear to be correct.

*starts chugging corn liquor*

"The future's uncertain and The End is always near."

Someone should write a book on conspiracy theories. Someone also should write a book about the Libertarian Moment - except for Seattle, where, apparently, they continue to have lots of "RESPECT MAH AUTHORITAH, AND GIVE ME YOUR GODDAMNED PROPERTY OR I'LL TAKE IT!" moments.

A follow up to Robby's article from yesterday.

Ron wrote a book? Why am I just now hearing about this?

*My wife just finished reading The End of Doom to me. I do all the driving and when I do she reads to me. This is one of my favorite ways to spend my time.

Ron, I bought the book because I noticed my wife was beginning to get a bit down about all of the doom and gloom being screeched these days. I tried explaining to her that despite the naysayers and luddites efforts the smart people win in the end and we are on a positive trajectory. I topped that off with having her read your book. It worked.

Thank you Ron.

Maybe I should read it, I tend to be a pessimist.

I was going to go the the annual Pessimists of America meeting, but it was canceled. They didn't think anyone would show up.

Lol

He'll be here all week. Try the veal.

The meeting was moved to the Nihilist Convention Center. I'd tell you to tip your waitress, but what's the point?

My wife does this too. It's mighty white of her. I don't understand how she can stand to read while the car is rolling. When I try to read in the car, the words start swimming and I get sick to my stomach within minutes.

Ditto.

Maybe women have thinner inner ear fluid.

I read that women tend to get car sick more easily then men.

Or, at least, that is what a single unreplicated study says.

It's mighty white of her.

Not appreciated.

It's a Thank You for Smoking reference. One of my favorite movies.

"The end of Panglossian optimism?"

Leibniz' real ideas were a limitation on God. The world is as good as it can be given God's limitations.

And in the end, despite what Candide says to him, even the caricature that was Pangloss was right. Things did turn out as well as they could have given the limitations of the real world.

"While Pielke strikes a world-weary pose of intellectual ennui over a supposedly "stale" debate, he oddly fails to mention that there is between me and the Neo-Malthusians one big difference: My predictions have consistently proven right and theirs wrong."

Damn straight!

Maybe Bailey should have told Pielke that he needs to "cultivate his garden".

That's a euphemism for "shave his pubes" I haven't heard lately.

That would mean you're poorly read and...uneducated.

Maybe you're good at math?

So. Serious question on a Friday afternoon.

Why is the libertarian fold?or at least the ranks of Ron Paul supporters?so disproportionately filled with unkempt white guys firmly planted on the autism spectrum? I love my libertarian brethren, but they're so much more fun to hang out with online than in real life.

Nice.

you consider that a serious question? and they are the autistic ones?

It's a sockpuppet. Just ignore the fucking thing.

BUT I NEED TO ARGUE WITH IT

No, not a sock puppet. When I was in school, I was active in our campus libertarian student organizations and was one of two staunchly libertarian voices on Student Senate (we lost on very fucking vote, but oh, well, we had fun), but there were only a couple I could ever stand to spend time with. Most of them had no social skills whatsoever, and few were capable of verbalizing an argument that didn't make us sound like a bunch of raving lunatics. Take those guys handing out jury nullification literature in Colorado, for example. Why can't they spend five minutes to make themselves look presentable? Why are the only examples of libertarian thought the public ever sees the ones who make us look like freaks?

Because libertarian tendencies are probably an outlier of typical human behavior which leans more towards tribalism.

Interesting point. I was going to say that the reason I'm puzzled by this phenomenon is that from my perspective, libertarianism is the thinking-man's philosophy, by which I mean that it should be the default position of anyone with intelligence and advanced reasoning skills. But on second thought, these arguments are not incompatible. Tribalism is neither intelligent nor rational.

I think it's at least partially a result of the way tribal conformists treat those outliers in their formative years. You show me a kid who was unpopular, awkward, and picked-on in school and i'll show you someone who has good reason to disbelieve the notion that majority rule is all that great.

"You show me a lazy prick who's lying in bed all day, watching TV, only occasionally getting up to piss, and I'll show you a guy who's not causing any trouble."

? George Carlin, Brain Droppings

Weel, with normal folks, unless they are systematicly subjected to a policy of injustice, they go ahead and conform and submit to participate in the comedy of authority. Some folks will get disillusioned if they see others treated unjustly, but that seems pretty rare. These experiences abnormalise some folks, enforcing respect of the reality principle as a necessary survival skill. Truth and reason are valorised, and in consequence one's ability to carry on with the pretense of power becomes very difficult. So that's where most free folk probably come from. Then there's a rare few, such as myself, who seem to have been born incapable of entertaining the pretense or acting his assigned part in the charade at all convincingly. It's a blessing in that there never is any temptation to submit, because submission is simply something of which one is entirely incapable. It also seems to be the sort who inspires an extra share of hostility from the delusional majority, but who is at the same time largely suffers none of the psychic trauma that the slightly less abnormal seem to get out of considerably less hostility. It would never occur to me that others have some obligation to "accept" me or to be kindly towards me or anything, or that I should feel bad about it if they don't. It would never occur to me to take the fact that more people believe one thing than believe another should be given any weight in evaluating the relative merits of each belief.

The consciousness of freedom makes one's interpersonal relations much simpler, easier, and less prone to resentment and despite. Seems a person can quite easily tolerate a lot of difficulty if he doesn't succumb to the delusion that other people (or "society") are under some obligation to provide him with aid and comfort with no reciprocal consideration on his part. Sometimes a person can't get by on his own, but if it just isn't worth it to others to put themselves out to carry him along, what the fuck can you do? There may be an ethical question, but it's got to be arsked and answered by the person providing aid, not by the person who can't get by without it, and especially not by some unimplicated third-party busybody who isn't willing to step in and do anything himself.

Fuck off, sockpuppet. You're as transparent as you are stupid.

It's a sockpuppet. Just ignore the fucking thing.

Whose?

I smell bo/whoever runs bo

I have been using this handle for the better part of 16 years. I've registered it on literally hundreds of websites, and it's never been taken on any site I've ever tried to register it on. By all appearances, there is only one person in the world using this handle.

A sockpuppet I am not.

My father was a metallurgist who specialized in the concentration of Gold, Nickel, and Zinc ores for over 50 years.

I once asked him about the subject of this book, that is, the supply of raw materials. His answer: "There are enough metal ores in the continental united states to supply our country for as long into the future as you care to look. The reason that almost none of it is being mined is because of environmentalist's opposition."

He then tossed me copies of several professional periodicals and had me count the articles on environmental issues vs. articles actually pertinent to metallurgy. The articles complaining about greenies won by 2:1. I was about 15 years old and that was my first real introduction to the nature of 'environmentalism'.

Given that we're starting to realize that other bodies orbiting in our Solar System contain more natural resources than we ever could have imagined, and given that those resources could not have been derived from biotic sources, I'm surprised that there hasn't been more inquiry into the possibilities that our current origin models, while not necessarily wrong, might be incomplete and in need of enhancement. For example, given the immense stores of hydrocarbons elsewhere in the Solar System, why couldn't oil have been produced through abiotic processes here on Earth? And what untold mineral treasures lie beneath the crust? Is it just that there will never be any feasible way in which these theoretical resources could be extracted in an economical fashion?

I had a professor that pushed the abiotic oil thing a little (not shoving it down our throats, just exposing us to a scientific debate that everyone thought was settled [AS GOOD PROFESSORS SHOULD DO]).

I've always found that subject to be super interesting. Almost went to grad school in astronomical chemistry for it. Then I realized that astronomical chemists aren't a real thing and won't get jobs..

I can't get over your morphing into Rick Steves, Ron. I know I shouldn't keep mentioning it, but every time I see that picture, I send money to PBS.

Teasing Ron about looking like Rick Steves always makes me giggle.

Which makes me wonder if his co-workers tease him about this...

A good question to posit is why would Ron give the neo-Malthusians any credit to begin with. Neo-Malthusianism is an ideological bromide held by little red marxians who deal in peddling millenarist predictions of doom, like Pyramid readers and Bible-coders, and just as serious. The only reason anybody entertains their crazy predictions is because they're often cited by economically-ignorant journalists in the news media and in popular scientific journals (which are also populated by little red marxians).

Demographic transition was also a factor in Ehrlich's stupid lame ass theories being full of shit. Paul Ehrlich the wrongest man in the Galaxy.

Democratic free-market capitalism? It assumes that political mechanisms like democratic institutions (electorates, elected legislatures et cetera) have some sort of rightful legitimacy in dominating economic production. At the most basic level, people voting on issues concerning the life, liberty and property of other people is decidedly uncapitalist and anti-free market.

Capitalism is promoted and secured in our society despite democracy, not because of it. Insofar as democratic societies are good for free markets, it is only to the degree which democratic institutions don't have the authority to decide issues of life, liberty and property.

I don't? Well, why the fuck didn't you tell me that before?

Must be on the rag.

Also this:

http://hmpg.net/

Bleeding out of her/his ....whatever....

Fuckin' millennials.

Anus?

You look at Rick Steves and you just KNOW he is up to his neck in strange, amirite?

The beauty of that is that it's easy to pretend to be Rick Steves. Just take on the TV persona, be into pot, and don't speak foreign languages beyond a few choice phrases.

I didn't see the resemblance until he started using this photo as hist stock image.

Ahem. "I'm Rick Steves, bitch."

"You know what they say about a guy with a plural first name as his last name... ladies."

I'll tell you one thing if you are in the south of France or in Tuscany, go to the restaurants Steves recommends.

For the record, I like Rick Steves' shows and travel books.

Maybe you should tell him, Rick has a way of finding dissenters...