The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

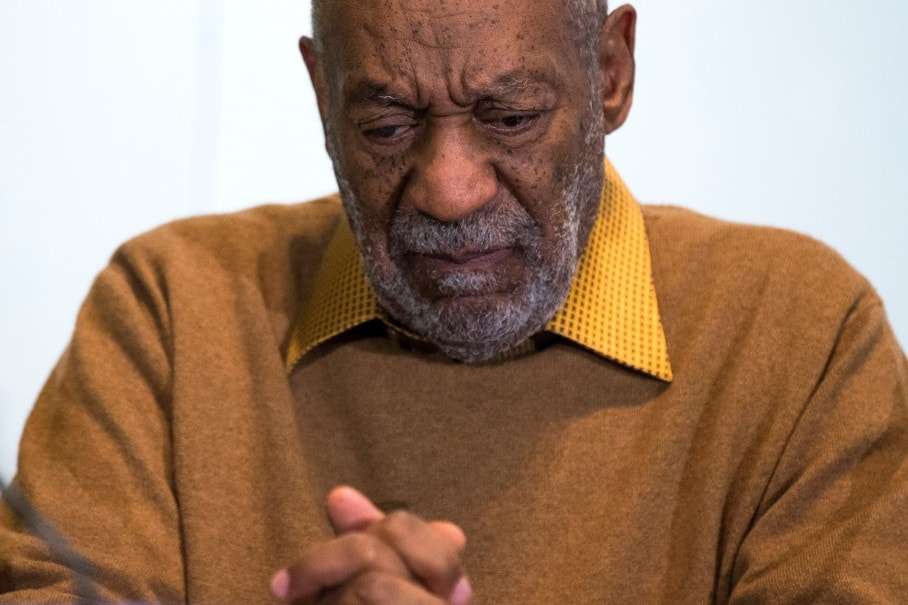

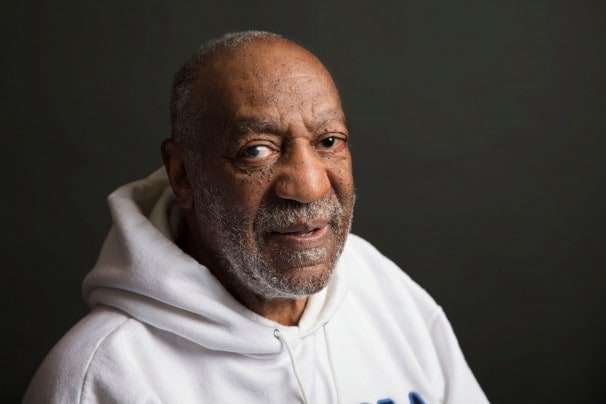

The unsealed deposition, and how Bill Cosby 'thrust himself into the vortex'

As Justin Wm. Moyer (Morning Mix, here at the Post) notes, Bill Cosby's damaging deposition from an earlier case was just unsealed - in part because of Cosby's past speech about moral matters:

While many lauded Cosby for tackling a delicate subject so directly, it wasn't long before the trouble began. Before the allegations of sexual assault surfaced, critics lambasted his conservative prescriptions for black America. After the accusations mounted over the past year, the Pound Cake speech was seized upon as an example of gross hypocrisy.

[Bill Cosby's] Pound Cake speech [taking many black parents to task] has resurfaced in yet another incarnation that no one could have predicted. It was cited by a U.S. district judge as a legal justification for unsealing a deposition that was deeply damaging to Cosby, the same document made public yesterday by the Associated Press that showed that Cosby acknowledged in 2005 that he intended to give Quaaludes to young women with whom he wanted to have sex, as The Washington Post's Paul Farhi reported….

In his memorandum, Judge Eduardo C. Robreno said the speech, and Cosby's general posture as a "public moralist," made the deposition a legitimate subject of public interest sufficient to override Cosby's objections to its disclosure. "The stark contrast between Bill Cosby, the public moralist and Bill Cosby, the subject of serious allegations concerning improper (and perhaps criminal) conduct, is a matter as to which the AP - and by extension the public - has a significant interest," the judge wrote.

Some people have questioned this, on the grounds that the decision may deter people from engaging in public commentary (especially hot-button public commentary) - speak out, and you lose various privacy protections. (As Judge Robreno acknowledges, depositions, unlike testimony in court, are quite often not made public: "[A]lthough 'there is a presumptive [common law] right to public access to all material filed in connection with nondiscovery pretrial motions,' there is 'no such right as to discovery motions and their supporting documents,'" and "a court must weigh the injuries that disclosure may cause against the other party's or the public's interest in the information.") And the deterrence won't just be of people who are afraid that many women might accuse them of rape, but also of people who are facing much more mundane - and less morally culpable - controversies.

At the same time, Judge Robreno's rationale has a good deal of precedent, coming from the constitutional law of libel. Here's an extended passage in which the judge explains his rationale:

The Supreme Court has recognized that "discovery … may seriously implicate privacy interests." However, the precise contours of a party's privacy interest may expand or contract depending on the public's interest in either the party or the information at issue….

The Third Circuit [i.e., the federal court of appeals that has jurisdiction over Pennsylvania, where the case is being litigated -EV] has recognized a curtailment of this interest for persons holding public office. Although it has not expressly extended this principle to "public figures" outside the category of office holders, [the Third Circuit precedents] suggest that the privacy interest may be diminished when a party seeking to use it as a shield "is a public person subject to legitimate public scrutiny."

Although Defendant is a public person in the sense that his name, fame, and brand are worldwide in scope, he does not surrender his privacy rights at the doorstep of the courthouse. Were this so, well-known nongovernmental public figures, visible in the public eye but pursuing strictly private activities, would be subject to spurious litigation brought perchance to gain access to the intimate details of their personal lives. Under these circumstances, the potential for abuse is high.

This case, however, is not about Defendant's status as a public person by virtue of the exercise of his trade as a televised or comedic personality. Rather, Defendant has donned the mantle of public moralist and mounted the proverbial electronic or print soap box to volunteer his views on, among other things, childrearing, family life, education, and crime [citing the Pound Cake speech and others]. To the extent that Defendant has freely entered the public square and "thrust himself into the vortex of th[ese] public issue[s]," Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 352 (1974), he has voluntarily narrowed the zone of privacy that he is entitled to claim.

Gertz is a leading libel case, and "thrust himself into the vortex" refers to the libel law category of "limited public figure." Generally speaking, if you're an ordinary person, and someone says false and defamatory things about you (on matters of public concern), you can get compensatory damages for libel if you can show the speaker was negligent, which is to say the speaker failed to reasonably investigate the facts.

But if you're a public official or a public figure, you can't get such compensatory damages unless you can show the speaker actually knew the statements were false or at least were quite likely to be false - a much higher standard for you as a plaintiff to prove. (This is the famous but misleadingly named "actual malice" standard.) And one way you can become a public figure is by "thrust[ing your]self into the vortex" of a public controversy, in which case statements about you and your character that relate to the controversy are subject to this hard-to-satisfy "actual malice" test.

Judge Robreno is thus borrowing some (but not all) aspects of libel law here: If you are a public official or a limited purpose public figure, you have less protection for your reputation under libel law. Likewise, you have less protection for your privacy when it comes to keeping depositions sealed. The way you can become a limited purpose public figure is by speaking out on controversial topics. And "the stark contrast between Bill Cosby, the public moralist and Bill Cosby, the subject of serious allegations concerning improper (and perhaps criminal) conduct, is a matter as to which the AP - and by extension the public - has a significant interest."

So Judge Robreno's rationale, it seems to me, has some helpful precedent behind it. To be sure, it's an argument by analogy, not an argument from binding precedent. One can either question the libel law precedents themselves, or conclude that they ought not be extended here, because of the risk that this "speak out, and you lose part of your privacy rights" approach would deter speaking out. Still, the argument seems to me to be a sensible one, and rooted in a well-developed body of libel law.

Finally, note that Judge Robreno isn't willing to apply the same approach as in libel law with regard to the other main class of public figures, besides the limited-purpose ones (and the public officials): people who are public figures because they are famous for their roles in entertainment, sports, and the like. When it comes to libel law, those people are treated the same as public officials and "thrust themselves into vortex" limited purpose public figures. Indeed, even if Cosby had never spoken out about moral matters, he would have been a public figure under libel law, because he's so famous. But Judge Robreno concludes such fame alone (without the involvement in public commentary) does not suffice to reduce a famous person's protection against disclosure of depositions; it is the public comment, not the fame as such, that is doing the job here.

Show Comments (0)