The Did-Something Candidate

Scott Walker stands out in the 2016 field for running on his record. How does it stack up?

On April 13, when Sen. Marco Rubio (R–Fla.) officially announced that he was running for president, the first-term senator didn't mention a single successful policy that he had championed while in office. A day earlier, when Hillary Clinton launched her long-awaited White House bid, her campaign website didn't even have an issues page.

And then there was Scott Walker.

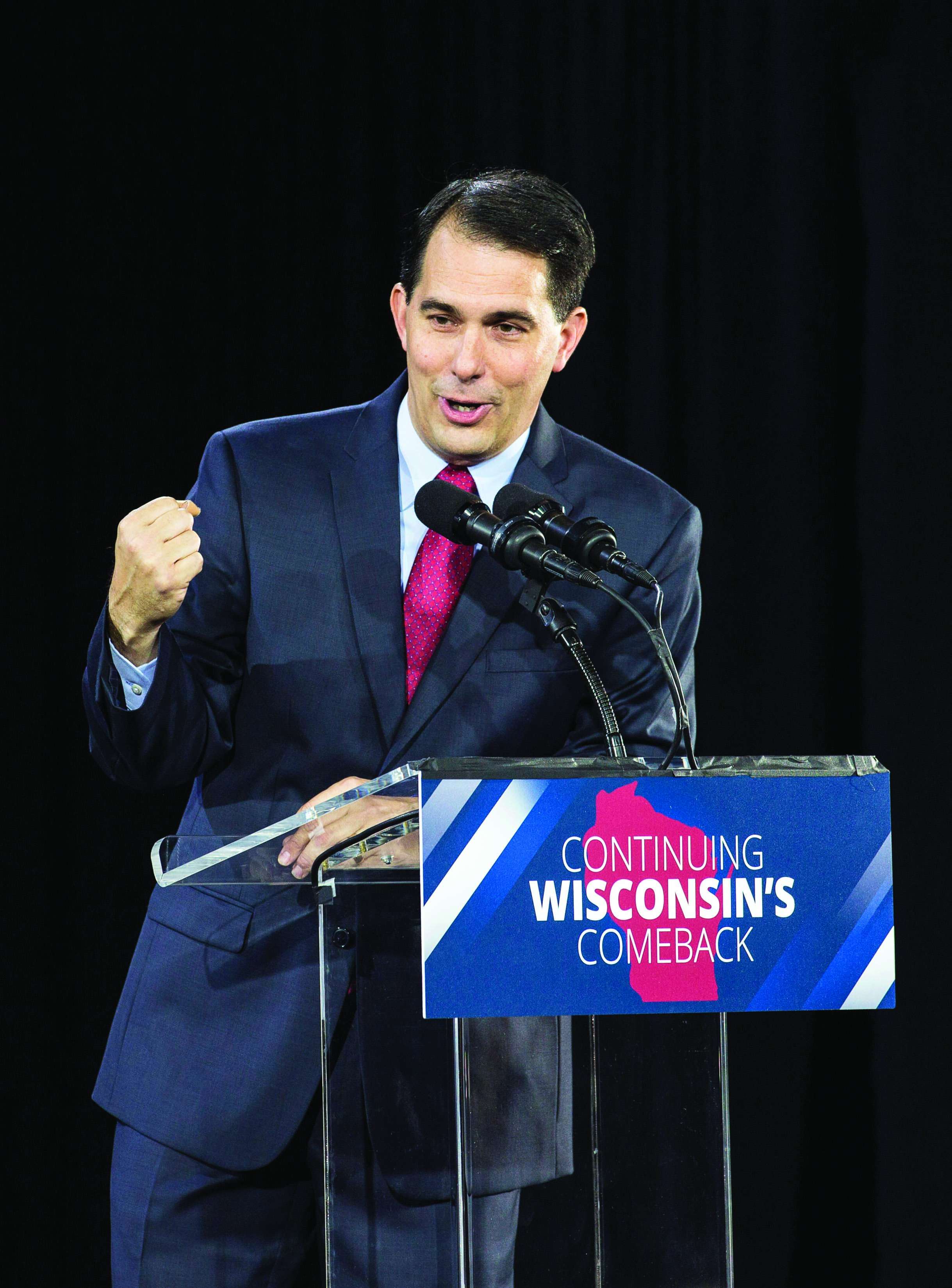

The Wisconsin governor, best known for his hard-fought, victorious showdowns against public sector unions, stands out in the field as the upper-tier potential candidate (he had not officially announced as of press time) most aggressive in touting his recent job performance. In wave-making pre-campaign speeches—a January address at the Iowa Freedom Summit that catapulted him from 4 percent in local polls to the head of the Iowa pack, and a February speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) that solidified his place near the top of national surveys—Walker didn't just talk about what he would do. He talked about what he did.

At CPAC, Walker's speech opened with the same kind of fuzzy, patriotic uplift you see in almost every modern presidential campaign speech-how he "grew up loving history," how he loved "reading about our Founders" who "were like superheroes" to him, how he's "the son of a small-town preacher and a mom who was a small-town secretary," how he seeks to "reignite the American spirit, to move this great country forward."

But then came an extended section that read more like a professional C.V. Wisconsin, Walker bragged, went from a 9.2 percent unemployment rate in 2010 to 5.2 percent at the end of 2014. Not only did he put an end to public school teacher seniority and tenure, and not only did he establish the ability to hire and fire on merit, but the changes produced results: rising graduation rates, rising reading levels, the second-best ACT scores in the country. He described Wisconsin as a state "that had been taxed and taxed and taxed" until he came along and reduced the burden by nearly $2 billion, with more property-tax cuts to come. "Because of our reforms, our state is indeed better," Walker said.

And what's really remarkable is that it's all true—although some caveats apply.

Wisconsin's unemployment rate has dropped. But some of that is just the natural effect of the dwindling recession; nationwide over the same time frame, the rate has decreased from 9.8 percent to 5.6 percent. Walker campaigned on adding 250,000 jobs to the economy during his first term, but fell about 100,000 short.

The ACT scores are as strong as he claims, although, as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported last year, test results also showed that about one-fifth of Wisconsin graduates who took the ACT were unprepared for college on any of the test's major dimensions. The four-year high-school graduation rate rose from an already high 85.7 percent in 2010 to 88 percent in 2013—one of the country's very best rates—but minority graduation rates in two big urban areas, Madison and Milwaukee, struggled to keep up.

Under Walker the state has indeed reduced taxes substantially, but not without tradeoffs. The governor announced in February that he would delay a $108 million principal payment on Wisconsin's debt in order to help fill a $283 million deficit. Over the next two years, the additional costs from this restructuring will stick more than $19 million onto the state's tab.

Still, Walker's record is real. Unlike the showy senatorial trio vying for the nomination -Rubio, Rand Paul, Ted Cruz-he can talk about his pragmatic work as an executive. Unlike his perceived main rival for establishment GOP affection, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, Walker governed through the more challenging post-recession era, and his record does not include strong support for a federal education program—Common Core—that is widely mistrusted by the conservative base. And unlike fellow sitting governors Bobby Jindal of Louisiana and Chris Christie of New Jersey, Walker is showing well in early polls and is able to campaign on a story of governance that has at times captivated the nation.

The Fighter

One reason that Walker had shot to the top of several national Republican primary polls by mid-April is that he checks off all of the GOP's traditional boxes: He's a committed Christian, the son of a Baptist preacher. He's a fiscal conservative who cut taxes and closed budget deficits. He's a foreign policy hawk, albeit one without much experience on the issue. He loves Ronald Reagan and frequently refers to labor leaders as "union bosses."

But most of all, Walker knows how to pick political fights and win them. The kinds of fights he likes to pick share a number of qualities. They have real policy consequences, but they're also heavy on political symbolism. They demonstrate his commitment to conservative, Republican governance while doing double duty as partisan protest. And he's been picking and winning these fights since even before he took office.

His predecessor, Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle, had managed to coax the Obama administration into awarding an $810 million stimulus grant to build a train line between Wisconsin's two major metro areas, Madison and Milwaukee. Doyle pitched it as a jobs plan in the short term and an economic boon in the longer term. He countered in-state critics of the idea by saying that it was all going on the federal government's tab.

Walker campaigned against the train, arguing that it would inevitably cost more than expected, leaving the state to fill in the gaps—and that even if it didn't, Wisconsin would still be on the hook for millions every year to support repairs and regular operations.

In December 2010, barely a month after Walker had won the governorship, the federal government gave up on the plan and cancelled the line. For Walker, this wasn't just a victory over his Democratic predecessor. It was a victory over the Obama administration and one of its biggest initiatives. A major build-out of new rail lines across the nation was one of the chief selling points for the stimulus, and a high priority within the administration. "High-speed rail is coming to Wisconsin," Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood had declared in July 2010. "There's no stopping it." Yet before Walker even officially took over, he had.

Less than a month later, Walker would make good on another campaign promise. The day after taking office, he called a special session of the legislature to tackle job creation, and, with the help of Republican majorities in both the Senate and the Assembly, he quickly passed a series of measures exempting health savings accounts from taxes, boosting tax credits for economic development, creating new credits and deductions for out-of-state businesses that moved to Wisconsin, and introducing new restrictions in personal injury cases, including caps on damages and changes to the handling of expert testimony—a limited but consequential type of tort reform.

Walker's opening move as governor, in other words, was to pick a fight with trial lawyers and with state Democrats, some of whom bitterly objected to his plans. Responding to the proposals, Rep. Peter Barca, the Democratic Minority Leader in the State Assembly, released a statement insisting that the tax cuts Walker had championed were not jobs bills at all and would add to the state's already considerable deficit.

Public Sector Union Power

Those initial fights would soon be subsumed by Walker's drawn-out battle with public sector unions.

Officially, the standoff began when Walker took office in January 2011 and started looking for ways to close a $3.6 billion hole in the state's upcoming two-year budget cycle. But its origins go back decades, to the very beginnings of public sector unions in the United States.

Wisconsin was the first state to allow most public employees to unionize and bargain collectively. It's the original home of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, the nation's largest public employee union. Long before Walker took office, Wisconsin's public sector unions had become deeply entrenched in state politics, and even Republican governors often sought to avoid conflict with them. They were immensely powerful.

As the executive of Milwaukee County for eight years before becoming governor, Walker had to negotiate with these unions in order to implement his budget plans. Union leaders, Walker says in his 2013 book, Unintimidated: A Governor's Story and a Nation's Challenge (co-written with Marc Thiessen), rejected any reforms that would pare back benefits; they preferred layoffs to benefit cuts, leaving few savings options for local officials.

As governor, Walker was determined to change the system. His model for doing so was then–Gov. Mitch Daniels of Indiana, who had instituted a slate of public sector union reforms, including an end to collective bargaining, immediately after assuming office in 2005. There were some procedural and policy differences between what Daniels did and what Walker ended up doing—Daniels, notably, was able to end collective bargaining via executive order—but the Indiana reforms showed Walker the way forward.

Shortly before taking office, Walker went to a Republican Governors Association conference where, according to his book, he spent a significant amount of time grilling Daniels about his reforms. "I wanted to hear everything he had learned from his experience with collective bargaining in Indiana—how he did it, how his opponents responded, and what the results had been," Walker writes. "Mitch, as much as anyone, has the clearest road map for the two big issues I ran on, fixing the economy, jobs, and fixing the budget, spending," the governor said in a 2011 interview, according to Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporters Jason Stein and Patrick Marley, authors of More Than They Bargained For: Scott Walker, Unions, and the Fight for Wisconsin (from which this article draws heavily).

Daniels didn't just give Walker advice on what to do. He gave him advice on how to do it: "Whatever you decide to do, go big, go bold, and strike fast," Walker recalls him saying. That's just what Walker did.

The Fight

In February 2011, Walker introduced his budget repair bill, which would become known as Act 10. It called for public workers to pay about 5.8 percent of their pension out of their paychecks, increased the employee share of health insurance premiums from about 6 percent to 12.6 percent, and cut billions in aid to Wisconsin's schools and local governments. In order to help offset the pension and health payments, Walker's plan made union dues optional for workers. And in order to help schools and governments deal with the cuts, he called for strict limits on collective bargaining, which would allow local officials to find the sort of efficiencies that unions had prevented him from implementing as Milwaukee County executive.

Walker's initial plan was to pass Act 10 quickly and move on, per Daniels' advice. Both the Assembly and the Senate had flipped to majority Republican control at the same time that Walker had been elected. After overcoming some initial skepticism from a few Republican legislators, he knew he had the votes.

But the state also requires three-fifths of the Senate—or 20 senators—to be present for any bill with certain major fiscal impacts. The budget repair bill was one such bill. There were only 19 Republicans in the Senate, meaning that if no Democrats were present, no vote could be held.

So Wisconsin's Senate Democrats packed up and left the state, camping out in Illinois, where Wisconsin authorities could not retrieve them.

In the meantime, the state Capitol in Madison became the locus of a massive protest. Tens of thousands camped out both in and around the building for weeks. The Capitol building and the grounds around it took on a circus-like atmosphere. People showed up in costumes. Reporters from Comedy Central's The Daily Show arrived towing a camel. The protesters, some of whom were organized by labor groups and some of whom were connected to Occupy Wall Street, set up daycare and medical facilities. Counterprotests sponsored by conservative groups backed the embattled governor. A group of doctors arrived and wrote sick notes so protesters could get out of work. (Twenty of those doctors were later disciplined by the state's Medical Examining Board, and others were fined by the University of Wisconsin medical school.)

It wasn't all fun and games. Walker and his fellow Republicans felt like they were under siege. Walker received multiple death threats, some of which were directed, with gory specificity, at his wife and family. State Democrats and their supporters, backed heavily by labor groups, staged a number of highly theatrical procedural protests, including a so-called citizens filibuster and a marathon 61-hour debate session over the bill's collective bargaining provisions. The showdown dragged on for weeks.

Why Walker Didn't Bargain

The most telling moment in the battle over Act 10 came early on, just one day after Senate Democrats left. The state's public sector unions announced that they would accept the hikes in benefit contributions if the governor would agree to nix the collective bargaining limits. It was, by Walker's own admission, a smart public relations move. The benefits changes he sought polled well. The collective bargaining reforms didn't.

This was the moment when Walker could have negotiated, when he could have backed down and settled for the considerable savings that the benefits overhaul still would have provided. But he didn't.

To understand why Walker didn't bargain, you have to go back to December 2010, the month before Walker took office. Democrats in the state legislature had just lost power in both the legislature and the Senate. But, under pressure from public sector unions, they held a lame duck session and tried, as a final act, to pass a new labor contract before Walker took office. In the Assembly, a Democrat serving jail time was pulled out on work release in order to pass the bill, angering Republicans. In the Senate, the measure failed, barely, when the outgoing Democratic Senate Majority Leader cast a surprise vote against it. The episode led Walker to believe that state Democrats and their union allies were not acting in good faith.

Walker's resistance also owes something to his extreme reverence for Ronald Reagan. Walker is—there's no other way to put this—a Reagan nut. He and his wife Tonette were married on Reagan's birthday, and according to Walker's book, every year the couple hosts a party to celebrate both events, where they serve Reagan's favorite foods and play patriotic music.

When Walker introduced his budget repair bill to his senior staff, he started by telling a story about Ronald Reagan's famous showdown with air traffic controllers in 1981. Some 13,000 members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization had gone on strike. Reagan demanded they return to work in 48 hours. When they didn't, he fired more than 11,000 of the strikers, decertified their union, and prohibited the fired employees from all future federal employment.

"It sent a message that Reagan was serious—that he had backbone, that he was going to fulfill his promises, and that he was not going to be pushed around," Walker wrote in his book. "It helped win the Cold War."

Refusing to back down on collective bargaining, Walker wrote, "was our chance to take inspiration from Reagan's courage." And if it succeeded, "maybe our display of courage might just have an impact beyond Wisconsin's borders."

Though extremely contentious, the collective bargaining provision's passage was never really in doubt. Republicans had the votes, if the Democratic senators returned, and even if they didn't, there were procedural tactics that would allow them to move the bill. A little more than two months after Walker took office, Senate Republicans split Act 10's fiscal provisions in such a way that the three-fifths quorum requirement was no longer applicable, and the measures became law.

Skirmishing continued long after the fight was won—there were court battles, a 2012 recall election, a 2014 re-election. But not only did Walker and his plan survive, enough time has elapsed that the governor can point to concrete benefits from Act 10 (more than $3 billion in savings, his office estimates, $2.35 billion of which came from public employee pensions), many of which Walker's office has catalogued on a site devoted to the results of Act 10. Those savings have allowed local authorities the kind of flexibility that Walker didn't have when he was a county executive. Meanwhile, the opt-out provision for union dues has made it noticeably tougher for state unions to organize and raise money, a fact not lost on national Republicans looking to deplete one of the Democratic Party's main sources of funds.

Walker had successfully followed Daniels' advice, striking fast and winning big against the state's most powerful interest group. In March of this year, he followed up on his victory against public sector unions by signing a right-to-work bill prohibiting mandatory union dues in the private sector.

But what is the potential federal applicability of the governor's signature policy achievement? In April, Walker suggested in a radio interview that he might pursue a national right-to-work law, which would apply to states that don't currently have the policy, saying federal action was legitimate in order to establish a "fundamental" freedom.

Mostly, however, he portrays Act 10 as a telltale sign of unyielding Reaganesque leadership—an indication of his resolve and readiness to take on any number of other challenges, not all of which are obviously related to the showdown. "I want a commander in chief who will do everything in their power to ensure that the threat from radical Islamic terrorists does not wash up on American soil," Walker said in his CPAC appearance. "If I can take on 100,000 protesters, I can do the same across the world."

Wisconsin: Open for Business

Not everything Walker has done as governor has been a success. "Wisconsin is open for business," he declared in an election night victory speech. He posted a sign in his office with those last three words. One of the primary ways the new governor tried to make good on the slogan was by reimagining the state's Department of Commerce as a semi-private entity, the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation (WEDC).

Created by Act 7, a February 2011 law that came out of Walker's initial special session, the WEDC went live in July 2011, just a few months after the Act 10 showdown ended. The goal was to use the new quasi-public agency to lure companies into the state and make it easier for them to expand. The semi-private status would in theory free it from some of the burdensome rules and requirements of a fully public agency. But the WEDC would still be subject to public, political oversight from a board nominated by the governor and the legislature. Walker, as governor, would sit at the top of the board, and also pick the agency's chief executive.

Act 7 instructed the board to "develop and implement economic programs to provide business support and expertise and financial assistance" to companies operating, expanding, or starting up in Wisconsin. The Act also requires the board to establish measurable goals for every program, and to collect, evaluate, and verify progress reports from companies receiving assistance.

In its first fiscal year, the WEDC spent a little more than $80 million, and authorized bonds and tax credits involving hundreds of millions more, while running some 30 different development programs—everything from business loans to tax credits, grants, and aid to local governments. Almost every dollar it spent came from public funding.

Was the money well spent? It's impossible to say, because in that first year, the newly created agency failed almost entirely to provide accountability for its spending. According to a May 2013 report by the state's Legislative Audit Bureau, the WEDC only collected 45 percent of the required progress reports from recipients of its funding. The agency didn't verify that the performance reports it did receive were accurate, even though it is required by law to do so. No success benchmarks were established for one-third of its programs. Funds were awarded to ineligible beneficiaries, and expenditures within the programs were not monitored, in part because the WEDC staff didn't understand their own accounting system. The picture painted by the report was one of an almost total failure of transparency and accountability—the chief responsibility of the board, of which Scott Walker was the chair.

The audit wasn't a partisan attack: The two co-chairs of the Audit Bureau whose names are on the report are both Republicans. The agency promised to clean up its act, but in the years since it has continued to demonstrate serious financial control problems. In March, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that the WEDC was still not tracking how many of its loans and grants were being spent, as required by statute. It was still failing to follow the law.

At the same time, the agency struggled to maintain consistent leadership. In scarcely more than three years, the Journal Sentinel reported last September, the organization had gone through multiple CEOs and chief operating officers, in addition to four chief financial officers—one of whom quit the post less than a day after taking it.

Walker's office defends the creation of the WEDC, saying that Wisconsin's old Commerce Department was "an ineffective bureaucratic state agency" that necessitated a new approach, and notes that some of the organization's current problems were carried over from the old Department of Commerce.

But Walker now seems to believe his new approach requires further reforms: In his latest budget, the governor proposes merging the WEDC with the state's Housing and Economic Development Authority and placing it under a new board made exclusively of private sector appointees. Under the new plan, the merged agency would no longer be subject to public oversight at all.

The merger, Walker's office says, would facilitate "greater coordination of the state's economic development efforts within a single authority" and allow resources to "be shifted from overhead into economic development." The idea is "to reform government by merging state agencies to be more effective, more efficient, and more accountable."

In his book, Walker writes that "in the areas where government has an appropriate role to play…taxpayers not only deserve but should expect and demand that government carry out its functions exceptionally well." The WEDC is technically not a government agency, but it was created by government, funded by taxpayers, and overseen by elected officials—with Scott Walker chief among them. It is hard to make a case that the WEDC has functioned well, let alone exceptionally.

Regular Joe

In his book, Walker criticizes 2012 GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney, the consultant, capitalist, and former governor of Massachusetts, for failing to connect with average voters. It was "frustrating that Romney allowed himself to be portrayed as a defender of the rich and powerful instead of a champion of the poor and vulnerable," Walker wrote.

In his pre-campaign speeches so far, Walker has spent considerable time emphasizing his own Midwestern everyman relatability, in contrast to the dynastic Clinton and Bush families and the once-shiny intellectual dazzle of the current president.

During a mid-April GOP presidential confab in Nashua, New Hampshire, Walker talked up a 10-county Harley tour of the state. He showed off his Joseph A. Bank suit, which he said he got on one of the retailer's famous three-for-one sales. Later, when a bride whose wedding was being held at the hotel left her reception to see Walker, he posed for photos with the lucky couple. "You young kids have so much more to celebrate than some stupid political event," he reportedly said.

It may be a shtick, but it works. And up against Hillary Clinton, who attacks CEO pay while giving $300,000 speeches and bemoaning her own family's poverty, who has always struggled to relate to average voters, and who has lived life in the public eye as a political super-elite for a quarter century, it's easy to imagine it working even better. Clinton opened her campaign in April with a video talking about "everyday Americans." Walker actually comes across as one.

But Walker isn't like you. He isn't really an everyday American—if for no other reason than he's been running for office practically his entire adult life.

After losing a campaign for student president at Marquette University, a private Jesuit school in Milwaukee, Walker dropped out during his senior year, and in 1990, at age 22, ran for state assembly. He lost, but the episode provided an early glimpse at his political ambitions. "I had gotten a little bit too caught up in the office and not in the reason why you run," Walker recalled in a 2010 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel profile. "So it was a great, humbling moment for me."

The moment didn't last long. After brief stints working for IBM and the American Red Cross, Walker won his first election three years later in a new district. He went on to serve four more terms as a state representative. In 2002, he won a special election to become the executive of Milwaukee County, a position he held until 2010. In 2006, he campaigned for governor, but quit before the GOP primary.

Walker, in other words, is a lifelong political actor, a man who, by the time he became governor, had already campaigned in 10 different previous elections, all but two of which he had won. "Scott really had a plan and was hoping to be governor one day," his wife Tonette told the Journal Sentinel. "He saw that as somewhere he wanted to go."

'My View Has Changed'

Walker has made it clear that the next place he wants to go is the White House, but during the first few months of 2015, it was not always obvious what route he hoped to take.

As the governor's campaign ramped up, for example, he took a hard turn on immigration. As recently as 2013, he urged Republicans to "embrace" a "legal pathway" for undocumented immigrants in the United States and even seemed to back a path to citizenship. But this February he declared that he was opposed to "amnesty," and in April he told Glenn Beck that his first priority was shielding American workers from competition. "The next president and the next Congress need to make decisions about a legal immigration system that's based on, first and foreÂ- most, on protecting American workers and American wages," he said. Walker left no doubt that he had flip-flopped, telling Fox News, "My view has changed. I'm flat- out saying it."

Nor was this his only reversal. Walker, once an avowed opponent of any kind of ethanol mandate who described them as "big government" and "central planning," said in March that he'd be willing to "go forward on the Renewable Fuel Standard," which effectively requires American gas to maintain a minimum percentage of ethanol in its blend.

Yet in other ways Walker remained consistent, continuing, for example, to back dubious government interventions into his state's economy. In January, he called for the state of Wisconsin to issue $220 million in public bonds to build a new arena for the Milwaukee Bucks, calling the plan a "fiscally conservative approach."

Picking the Next Fight

In the years after the Act 10 struggle, Walker continued to pick fights.

Under Gov. Doyle, Wisconsin had been on track to set up its own Obamacare health insurance exchange and had commissioned a report from Massachusetts Institute of Technology consultant Jonathan Gruber analyzing its options. Under Walker, the state's newly created Office of Free Market Health Care took several steps in that direction. But in summer 2012, the governor announced that the state would not be setting up its own exchange, and he closed the office.

In September 2014, Walker announced a plan to require food stamp recipients to pass drug tests, which he argued would ensure that beneficiaries were more prepared for employment. The requirement would potentially violate federal law, however, and would almost certainly be opposed by the Obama administration. Walker welcomed the challenge. "We believe that there will potentially be a fight with the federal government and in court," he told the Journal Sentinel.

As more candidates continue to make their 2016 campaigns official, the word around Walker is that he'll hold off until June, after he finalizes and passes Wisconsin's new budget plan. After all, he needs more record to run on.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Did-Something Candidate."

Show Comments (48)