The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

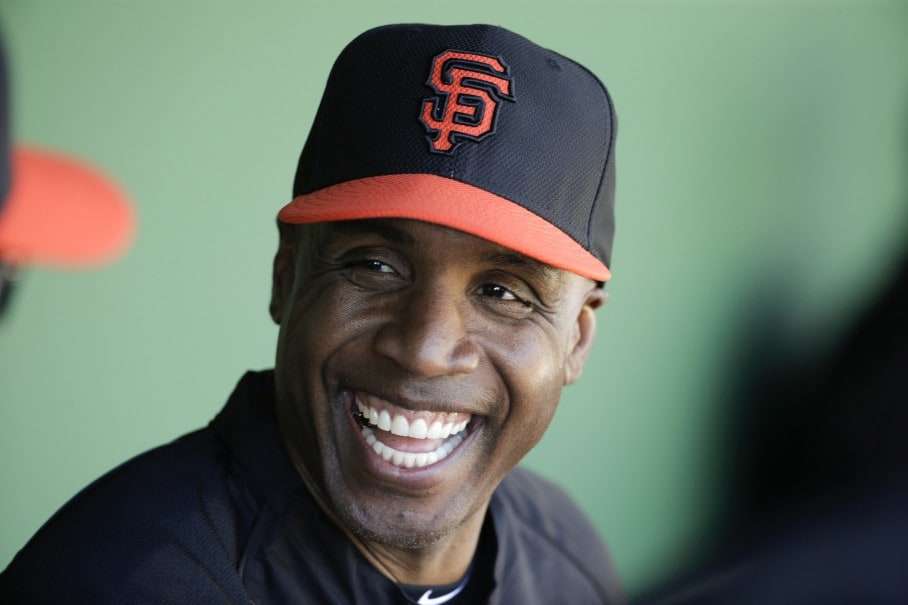

Barry Bonds obstruction-of-justice conviction thrown out by Ninth Circuit en banc

The decision, just handed down today, is here. Here's Judge Kozinski's concurring opinion, signed on to by five of the 11 judges on the en banc panel:

Can a single non-responsive answer by a grand jury witness support a conviction for obstruction of justice under 18 U.S.C. § 1503? …

Defendant, who was then a professional baseball player, was summoned before a grand jury and questioned for nearly three hours about his suspected use of steroids. He was subsequently charged with four counts of making false statements and one count of obstruction of justice, all based on his grand jury testimony. The jury convicted him on the obstruction count and was otherwise unable to reach a verdict.

The jury instructions identified seven of defendant's statements that the government alleged obstructed justice. The jury, however, found only one statement obstructive. That statement was referred to as Statement C at trial and is [italicized] in the passage below:

Q: Did Greg[, your trainer,] ever give you anything that required a syringe to inject yourself with?

A: I've only had one doctor touch me. And that's my only personal doctor. Greg, like I said, we don't get into each others' personal lives. We're friends, but I don't - we don't sit around and talk baseball, because he knows I don't want - don't come to my house talking baseball. If you want to come to my house and talk about fishing, some other stuff, we'll be good friends. You come around talking about baseball, you go on. I don't talk about his business. You know what I mean?

Q: Right.

A: That's what keeps our friendship. You know, I am sorry, but that - you know, that - I was a celebrity child, not just in baseball by my own instincts. I became a celebrity child with a famous father. I just don't get into other people's business because of my father's situation, you see.

Defendant was again asked about injectable steroids immediately following this exchange and a few other times during his testimony. He provided direct responses to the follow-up questions. For example, he was asked whether he ever "injected [him]self with anything that Greg … gave [him]." He responded "I'm not that talented, no." The government believed that those answers were false but, as noted, the jury failed to convict defendant on the false statement counts….

A. Title 18 U.S.C. § 1503(a), which defendant was convicted of violating, provides in relevant part as follows: "Whoever … corruptly or by threats or force, or by any threatening letter or communication, influences, obstructs, or impedes, or endeavors to influence, obstruct, or impede, the due administration of justice, shall be punished as provided in subsection (b)." Known as the omnibus clause, this language "was designed to proscribe all manner of corrupt methods of obstructing justice." We have held that a defendant "corruptly" obstructs justice if he acts "with the purpose of obstructing justice."

As should be apparent, section 1503's coverage is vast. By its literal terms, it applies to all stages of the criminal and civil justice process, not just to conduct in the courtroom but also to trial preparation, discovery and pretrial motions.

Indeed, it arguably covers conduct taken in anticipation that a civil or criminal case might be filed, such as tax planning, hiding assets or talking to police. And the text of the omnibus clause, in concert with our definition of corruptly, encompasses any act that a jury might infer was intended to "influence, obstruct, or impede … the due administration of justice." That's true even if no actual obstruction occurs, because the clause's use of "endeavors" makes "success … irrelevant."

Stretched to its limits, section 1503 poses a significant hazard for everyone involved in our system of justice, because so much of what the adversary process calls for could be construed as obstruction. Did a tort plaintiff file a complaint seeking damages far in excess of what the jury ultimately awards? That could be viewed as corruptly endeavoring to "influence … the due administration of justice" by seeking to recover more than the claim deserves. So could any of the following behaviors that make up the bread and butter of litigation: filing an answer that denies liability for conduct that is ultimately adjudged wrongful or malicious; unsuccessfully filing (or opposing) a motion to dismiss or for summary judgment; seeking a continuance in order to inflict delay on the opposing party; frivolously taking an appeal or petitioning for certiorari - the list is endless.

Witnesses would be particularly vulnerable because, as the Supreme Court has noted, "[u]nder the pressures and tensions of interrogation, it is not uncommon for the most earnest witnesses to give answers that are not entirely responsive."

Lawyers face the most pervasive threat under such a regime. Zealous advocacy sometimes calls for pushing back against an adversary's just case and casting a despicable client in a favorable light, yet such conduct could be described as "endeavor[ing] to … impede … the due administration of justice." Even routine advocacy provides ample occasion for stumbling into the heartland of the omnibus clause's sweeping coverage. Oral arguments provide a ready example. One need not spend much time in one of our courtrooms to hear lawyers dancing around questions from the bench rather than giving pithy, direct answers. There is, for instance, the ever popular "but that is not this case" retort to a hypothetical, which could be construed as an effort to divert the court and thereby "influence … the due administration of justice."

It is true that any such maneuver would violate section 1503 only if it were done "corruptly." But it is equally true that we have given "corruptly" such a broad construction that it does not meaningfully cabin the kind of conduct that is subject to prosecution. As noted, we have held that a defendant acts "corruptly," as that term is used in section 1503, if he does so "with the purpose of obstructing justice." In the examples above, a prosecutor could argue that a complaint was filed corruptly because it was designed to extort a nuisance settlement, or an answer was filed corruptly because its principal purpose was to pressure a needy plaintiff into an unjust settlement, or that the lawyer who parried a judicial hypothetical with "but that is not this case" was endeavoring to distract the court so it would reach a wrong result. That a jury or a judge might not buy such an argument is neither here nor there; a criminal prosecution, even one that results in an acquittal, is a life-wrenching event. Nor does an acquittal wipe clean the suspicion that a guilty defendant got off on a technicality.

We have no doubt that United States Attorneys and their Assistants would use the power to prosecute for such crimes judiciously, but that is not the point. Making everyone who participates in our justice system a potential criminal defendant for conduct that is nothing more than the ordinary tug and pull of litigation risks chilling zealous advocacy. It also gives prosecutors the immense and unreviewable power to reward friends and punish enemies by prosecuting the latter and giving the former a pass. The perception that prosecutors have such a potent weapon in their arsenal, even if never used, may well dampen the fervor with which lawyers, particularly those representing criminal defendants, will discharge their duties. The amorphous nature of the statute is also at odds with the constitutional requirement that individuals have fair notice as to what conduct may be criminal.

B. Because the statute sweeps so broadly, due process calls for prudential limitations on the government's power to prosecute under it. Such a limitation already exists in our case law interpreting section 1503: the requirement of materiality. Materiality screens out many of the statute's troubling applications by limiting convictions to those situations where an act "has a natural tendency to influence, or was capable of influencing, the decision of the decisionmaking body." Put another way, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the charged conduct was capable of influencing a decisionmaking person or entity - for example, by causing it to cease its investigation, pursue different avenues of inquiry or reach a different outcome.

In weighing materiality, we consider "the intrinsic capabilities of the … statement itself," rather than the statement's actual effect on the decisionmaker, and we evaluate the statement in "the context in which [it was] made."

We start with the self-evident proposition that Statement C, standing alone, did not have the capacity to divert the government from its investigation or influence the grand jury's decision whether to indict anyone. Here it is again:

That's what keeps our friendship. You know, I am sorry, but that - you know, that - I was a celebrity child, not just in baseball by my own instincts. I became a celebrity child with a famous father. I just don't get into other people's business because of my father's situation, you see.

The statement says absolutely nothing pertinent to the subject of the grand jury's investigation. Even when paired with the question that prompted it,

Did Greg ever give you anything that required a syringe to inject yourself with?

Statement C communicates nothing of value or detriment to the investigation. Had the answer been "I'm afraid of needles," it would have been plausible to infer an unspoken denial, with the actual words serving as an explanation or elaboration. But, as given, the answer did not enlighten, obfuscate, confirm or deny anything within the scope of the question posed.

The most one can say about this statement is that it was non-responsive and thereby impeded the investigation to a small degree by wasting the grand jury's time and trying the prosecutors' patience. But real-life witness examinations, unlike those in movies and on television, invariably are littered with non-responsive and irrelevant answers. This happens when the speaker doesn't understand the question, begins to talk before thinking (lawyers do this with surprising frequency), wants to avoid giving a direct answer (ditto), or is temporizing. Courtrooms are pressure-laden environments and a certain number of non-responsive or irrelevant statements can be expected as part of the give-and-take of courtroom discourse. Because some non-responsive answers are among the road hazards of witness examination, any one such statement is not, standing alone, "capable of influencing … the decision of [a] decisionmaking body."

This is true even if, as the government now argues, Statement C is literally false. An irrelevant or wholly non-responsive answer says nothing germane to the subject of the investigation, whether it's true or false. For example, if a witness is asked, "Do you own a gun?" it makes no difference whether he answers "The sky is blue" or "The sky is green." That the second statement is false makes it no more likely to impede the investigation than the first.

Statement C does not, however, stand alone. It was a small portion of a much longer examination, and we must look at the record as a whole to determine whether a rational trier of fact could have found the statement capable of influencing the grand jury's investigation, in light of defendant's entire grand jury testimony. If, for example, a witness engages in a pattern of irrelevant statements, or launches into lengthy disquisitions that are clearly designed to waste time and preclude the questioner from continuing his examination, the jury could find that the witness's behavior was capable of having some sway.

On careful review of the record, we find insufficient evidence to render Statement C material. In conducting this review, we are mindful that we must give the jury the benefit of the doubt and draw all reasonable inferences in favor of its verdict. At the same time, we must conduct our review with some rigor for the prudential reasons discussed above.

The government charged a total of seven statements, only one of which the jury found to be obstructive. Two of these statements (including Statement C) appear to be wholly irrelevant - verbal detours with no bearing on the proceedings. One statement is "I don't know," followed by a brief explanation for the lack of knowledge. The rest are direct answers that the government claimed were false, all concerning whether defendant's trainer had provided or injected him with steroids. In the context of three hours of grand jury testimony, these six additional statements are insufficient to render the otherwise innocuous Statement C material. If this were enough to establish materiality, few witnesses or lawyers would be safe from prosecution.

The decision to reverse was 10-1, with Judge Rawlinson dissenting, and writing a baseball-metaphor-laden opinion (complete with strikes one, two, and three, the absence of joy, and "cry[ing] foul," though query whether that fits better with other sports than with the concept of "foul" in baseball).

Thanks to How Appealing for the pointer.

Show Comments (0)