Garry Trudeau on Charlie Hebdo: 'At Some Point Free Expression Absolutism Becomes Childish and Unserious'

Doonesbury's creator accuses the French satirists of publishing 'hate speech' and 'crude, vulgar drawings.'

Like Doonesbury itself, Garry Trudeau's speech yesterday at Long Island University was entertaining at the beginning but eventually became tedious and smug. After opening with some funny reminiscences about his early struggles with unsympathetic editors, the cartoonist tried to tackle the topic of the murders at Charlie Hebdo. He did not take the position you might expect from a professional satirist. "Freedom should always be discussed within the context of responsibility," he lectured. "At some point free expression absolutism becomes childish and unserious."

Trudeau's talk took its turn for the worse halfway in, when he offered a garbled account of the Muhammad cartoon controversy of 2005. "Using judgment and common sense in expressing oneself were denounced as antithetical to freedom of speech," he told the audience. I seem to remember some responses to those cartoons that were more clearly antithetical to freedom of speech, including death threats and assassination attempts. Trudeau alluded to some of this, but he blamed the speakers, not the censors: "Not only was one cartoonist gunned down, but riots erupted around the world, resulting in the deaths of scores. No one could say toward what positive social end, yet free speech absolutists were unchastened."

And then he got to the massacre in France. Right after the killings, you may recall, an instant take was available for Charlie contrarians: You accused the outfit of hate speech, suggested it was "punching down," maybe pointed to some images that supposedly proved what a racist outfit the weekly was. This critique grew less tenable when people more familiar with the paper provided context for those cartoons and explained the anti-authoritarian, anti-establishment outlook that fueled them. The discussion left room for people to like or dislike the humor in Charlie's pages, but at least they knew which way it was aiming its punches.

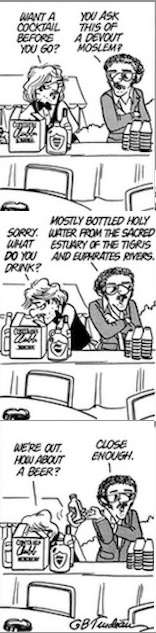

Unless they didn't pay attention. Then they ended up like Trudeau, stringing together phrases that feel even more stale now than they did in January: "By punching downward, by attacking a powerless, disenfranchised minority with crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons, Charlie wandered into the realm of hate speech."

But the biggest problem with Trudeau's talk isn't whether he got the paper's politics right. It's that he mixed up the debate about whether Charlie's politics were any good with the debate about how free it should be to express them. "Writing satire," Trudeau concluded, "is a privilege I've never taken lightly." But we should never think of satire as a privilege. We should see it as a fundamental right open to everyone, regardless of taste or talent. And while the defense of that right does not oblige you to embrace the content of anyone's speech, your critique of someone's speech in turn need not become an attack on the speaker's liberties. By turning his discussion of Charlie Hebdo into a denunciation of "free speech absolutists," Trudeau crossed that line.

Bonus links: The decline of Doonesbury. A better response to the killings from Robert Crumb. Some "crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons."

Show Comments (157)