What Clarence Thomas Learned from Malcolm X

Understanding the legal philosophy of the conservative Supreme Court justice.

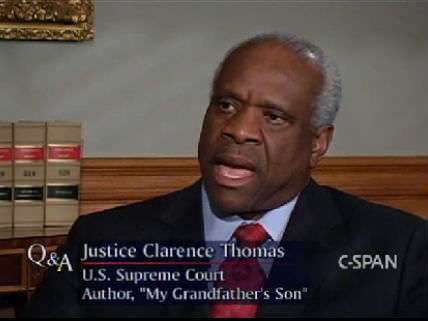

Writing in The Wall Street Journal this weekend, Fox News pundit Juan Williams praised Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as "the most influential thinker on racial issues in America today." According to Williams, Thomas "is reshaping the law and government policy on race by virtue of the power of his opinions from the bench." As Williams put it:

The principal point Justice Thomas has made in a variety of cases is that black people deserve to be treated as independent, competent, self-sufficient citizens. He rejects the idea that 21st-century government and the courts should continue to view blacks as victims of a history of slavery and racism.

Thomas certainly does reject many of the government solutions now in vogue for dealing with racial problems. But the source of that rejection is frequently misunderstood—especially by Thomas' liberal critics, who seem to think that he disfavors certain forms of affirmative government action because he believes racism to be dead and gone. New York Times columnist Charles Blow, for example, gave voice to that critique last year when he faulted Thomas for "being unable to acknowledge and articulate the basic fact that race was—and remains—a concern."

In point of fact, Thomas clearly believes that racism is a concern just as he clearly believes that the long shadows of slavery and Jim Crow continue to harm black Americans. Where Thomas differs from most liberals is in his pronounced lack of faith in the ability of ostensibly benevolent government officials to do the right thing.

Thomas made this point with great force in his 2002 concurrence in the case of Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, in which he joined a majority of the Supreme Court in upholding the constitutionality of a school voucher program in Cleveland over the loud objections of the teachers unions and the broader public education establisment. "While the romanticized ideal of universal public education resonates with the cognoscenti who oppose vouchers, poor urban families just want the best education for their children," Thomas wrote. "If society cannot end racial discrimination, at least it can arm minorities with the education to defend themselves from some of discrimination's effects."

If society cannot end racial discrimination. Those are not the words of a man who sees racism as a relic of the past.

Note also that Thomas combined his negative assessment of American society with an overarching emphasis on black self-empowerment and the removal of racist government obstacles. If that combination sounds familiar, it's because it tracks so closely with the agenda of the late black leader Malcolm X, who famously urged black self-reliance as a weapon in the long war against white supremacy—and who (like Thomas) famously distrusted the white liberals of his day.

Unsurprisingly, Malcolm X turns out to be one of Clarence Thomas' personal heroes. "I've been very partial to Malcolm X, particularly his self-help teachings," Thomas once told Reason. "I have virtually all of the recorded speeches of Malcolm X."

Here's what Malcolm X said in one of those speeches:

The American black man should be focusing his every effort toward building his own businesses and decent homes for himself. As other ethnic groups have done, let the black people, wherever possible, however possible, patronize their own kind, and start in those ways to build up the black race's ability to do for itself. That's the only way the American black man is ever going to get respect.

That is not the approach favored by today's liberals, who typically place great weight on the government's role as an agent of social change. But neither is it the approach adopted by many of today's conservatives, who all too often dismiss, minimize, or ignore black complaints about the persistence of racism.

By partially following the footsteps of Malcolm X, Thomas stands apart from both camps. While he may agree with the liberals about the pervasiveness of racial injustice, he rejects most of the preferred liberal solutions. And while he often sides with the conservatives in constitutional cases, he frequently writes separately from the bench, giving voice to a distinctive legal philosophy that's steeped in black history and owes much to radical black nationalism.

I don't know if all of that makes Thomas our most influential thinker on race or not. But the fact that his thinking so thoroughly resists easy left-right categorization certainly makes it interesting, and valuable.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

As long as constitutional constraints are what primarily inform his rulings.

And apparently there are none regarding schools strip searching kids.

Why does Clarence Thomas hate black people?

Something something... Uncle Tom... mumble mumble... race traiter...

What Clarence Thomas Learned from Malcolm X

How to be an Uncle Tom? Is that who Thomas learned that from? And here I thought Malcolm X was supposed to be this ultra bad ass radical.

and a Muslim too.

Well, you didn't see him hanging around with a bunch of country club crackas did you?

Hopefully he learned the line that white cop had in the movie:

"No one man should have that much power."

That's a true statement applicable to almost any situation or topic.

I haven't seen you around as much until the last few days, Jimbo. Did you earn your internet privileges back or did you manage to fool the parole board?

Truth be told, I got tired of the site for awhile, and I can't log in from work anymore since I changed jobs. So I might make a single comment when I first get home for the day, but that's about it.

Today my office was closed due to icey road conditions, so here I sit.

*scrolls down*

I wonder why.

It ruins it

And yet JJ responds to it. You know, I'm going to have a talk with his mom about this. Right after some science.

That happened where I live about 100 years ago. There was a black neighborhood, the richest in the entire country (though the whole city was very rich at the time thanks to oil), with black businesses and black prosperity underway.

Then a black kid touched a white girl in an elevator and the whites burned the entire neighborhood to the ground, killed hundreds, and looted whatever was left.

I wonder, how many rounds of outright theft of labor and property do blacks have to undergo before we stop prescribing bootstrap therapy?

Show me where that's happened in the last 50 years in the United States.

And no, I do not dismiss the idea of persistent, low-level subconscious racism, either. No pun intended, but situations this complex rarely have black-or-white causes or solutions.

The question is whether you acknowledge that generations of race-based oppression and theft might have something to do with conditions today. I'm open to another argument, but I have never heard one that isn't inherently racist.

But we can't solve the problem with current attitudes in this country. One of those is that however wealth was acquired in the past, it belongs just where it is, unless it was acquired via government transfer specifically targeted for social welfare, in which we should probably take that right back. This attitude is informed mostly not by libertarian attitudes against redistribution, but because people are racists and don't like redistributing to those people.

Whereas your opinion - that all wealth is suspect and subject to confiscation on a whim - is clearly the morally superior option.

One of those is that however wealth was acquired in the past, it belongs just where it is, unless it was acquired via government transfer specifically targeted for social welfare, in which we should probably take that right back.

I've not seen a single person on here advocate kicking in poor people or the elderly's doors and seizing back the wealth they acquired due to redistribution.

I have seen plenty of people advocate that we stop redistributing.

This attitude is informed mostly not by libertarian attitudes against redistribution, but because people are racists and don't like redistributing to those people.

I'd like to see a psychic citation of how you're gleaning that little nugget of information.

I have no doubt that, given human nature it's true for some. But to claim "mostly", is an unsupportable stretch with no scientifically valid backing. And you are the party of science, are you not?

I grew up poor and inherited fuck all from my parents. So point me to the person to which I owe money.

You owe some money to everyone you share a society with, and they owe some to you.

I give them a dollar, and they give one to me? Economic stimulus!

No, no, no.

You give *Tony* a dollar, he gives someone else 80 cents. Then he takes a dollar from them and gives *you* 80 cents.

And keeps the 40 cents for himself, as is his right as the great equalizer.

Velocity.

You owe some money to everyone you share a society with, and they owe some to you.

Man, if only there were a system, some way of letting people know what things cost, some kind of mechanism to exchange goods and services, some sort of process for settling debts and arbitrating disputes, why we might be able to establish just what it is that everybody owes each other and sort it all out.

Nah, any such system wouldn't satiate the envy of socialists, which is really what's it all about.

That system does a lot of things well, but it doesn't ensure universal access to basic needs, does it?

That system does a lot of things well, but it doesn't ensure universal access to basic needs, does it?

Unicorns don't exist, no matter how hard you try to pretend otherwise.

Also, goalposts should stay put.

There it is people in stark glory. The progressive claim that anyone against the welfare state is racist. And higher taxes, if you are against those you are racist. Actually, if you are against any progressive ideas at all you are racist.

It is all they have apparently.

Go fuck yourself Tony.

But you're an actual racist. As for other people, sure there could be people for lower taxes and against the welfare state who aren't motivated by racism. But I betcha to a person they care more about social welfare programs than they do all the other things government spends money on. And what was the seed of that bizarre fixation?

Re: Tony,

Those who are preoccupied with race are the racists.

There must be at least one, right, Tony? But the rest have to be motivated by race and not fiscal responsibility. I mean, how could they not?

Little red Marxian does what little red Marxians do.

No, people who think members of a certain race are inherently inferior is what I'm talking about. It's not like it doesn't exist. Go to any article linked by Drudge with a comments section.

Racism informs ant-federal-government attitudes and has from the start. No political idea in this country's history has been so thoroughly motivating as the idea that black people should be able to get paid for their work. After we fought a war over that, the resentments have stuck around more or less.

Wouldn't that be, I dunno, people who think that blacks can't succeed without affirmative action to help them? They can't feed themselves without government's help? Isn't that treating them as inferior human beings?

Re: Tony,

You have a personal issue with logic, don't you?

How is it not preoccupation with race that a person who thinks other members of a certain race are inferior?

IDIOT!

That would mean anybody who wants to vote the bums out has to be motivated by racism, including white liberals.

At least little red Marxian is consistent in his eternal fight against logic and reason.

I am an actual racist? No shit?

Ask anyone that knows me and they will say there is no evidence of that.

I am like Francisco, anyone who plays the race card immediately gets discounted. It is a means of shutting people up, an ad hominem meant to discount them. A way of avoiding rational discussion of the real issues.

Really, go fuck yourself with a red hot poker.

If we were having this conversation in person you would be on your ass holding a broken nose, you rat fucker.

I thought it was your week to drive for the car pool to the flag burning? Are you not going this week? I don't want to have to drive again.

well not flag, cross, cross burning. Flag burning is my other car pool.

I wish I could but my wife has me as designated driver for her 'girls night out'. I get to not drink, sit in the corner and make conversation with the local retired juvenile court judge (black dude) and see how many tobascoed oysters I can eat.

If I didn't have to suffer through that I would be happy to drive.

well see, Suthen, you're pissed about being stuck with the black dude. Ergo, racist.

/tony

All that needs to be said on the subject.

I am an actual racist? No shit?

Obviously. You believe that black people can get by on their own merit. That makes you racist. A true believer in equality knows that blacks are inferior and unable to succeed without a helping white hand. Preferably a progressive one. Any suggestion that blacks don't need government help is racist.

Whoever is running Tony today is doing a really bad job. They had a decent guy running him last week.

Consistency matters

I drink a lot on Oscar's night.

Tell the guy who was in charge last Thursday that he started out ok. He's the only credible handler.

I drink a lot on Oscar's night.

Why is that? Is Oscar not able to do that thing you like so much?

One of those is that however wealth was acquired in the past, it belongs just where it is

Well, I tell you what. I'm white and you know what I inherited wealth-wise from my ancestors? Jack dick. No one that I'm aware of for about 4 generations had anything to pass down. I think the sale of my grandparents' house was enough to pay off medical debts and the funerals. It was a pretty "inexpensive" house, btw. But here I am, by some magical force, not living in shit world.

How come the draft riots didn't do the same for the Irish? How come Asian immigrants, who had it arguably worse than black (especially under FDR) were earning more than whites on average within 50 years of being unable to own property in some states? The undeniable fact is racism is not remotely sufficient to explain the continuing poverty of the black community.

In fact, four decades of state meddling in the markets has left black urban poor with fewer economic opportunities than Jews or Italians decades before; the incompetent public education system has failed them as well where immigrant groups have succeeded largely by their own private school systems, and counterproductive affirmative action programs and a criminal justice system that puts public employees (police, lawyers, prison guards and judges) ahead of citizens caused this problem.

The state of African Americans today is more than anything a great example of the road to hell being paved by 'progressive' intentions.

And this horrible incident from 100 years ago proves that institutional racism still exists to this day! /DERP

But the same thing is going on today. Prisons are filled with black people who wouldn't be there if they were white and committed the same crimes. That's a bad, racist policy even you guys are aware of.

Are you saying college campus' are filled today with black people who wouldn't be there if they were white?

I asked you to show me where a white mob has burned down a successful black neighborhood sometime in the last 50 years, since that was the example you chose to hang your hat on.

I'll wait.

They're doing it in other ways, as I explained. Outright brutality and terrorism by whites against blacks has waned in recent decades. Good for us. We deserve another tax cut.

They're doing it in other ways

You're missing the point of the article, Tony. There's not a question of whether racism is an issue. The question is whether the issue is better addressed through government intervention (top-down) or through Malcom X's self reliance.

Self-reliance by segregating the races and giving blacks their own nation, a view he later recanted. He believed in achieving justice "by any means necessary" and said that if socialism improved the lives of black people, then he was for it.

"He believed in achieving justice "by any means necessary" and said that if socialism improved the lives of black people, then he was for it."

Well, it doesn't. So I don't think he'd be for it.

Brother Malcolm was pretty much a socialist. Had he lived, he probably would have evolved to have advocated something similar to the Pan-Arab/Pan-Muslim socialism of the PLO or the Ba'ath Party. He was assassinated just 1 year after the founding of the PLO. So it's highly likely the zeitgeist would have led him in that direction.

Granted, I'm a little out of my element here, but I've always interpreted Malcom X's speeches as arguing that no one can "give" blacks their own nation. He saw that as something they needed create themselves.

And the more reliance there was on a federal government hand out, the more difficult it would be to create that nation.

If you substitute "zoning board" for "white mob", and "built a freeway through" for "burned down", I bet we could find one.

I don't know if it's actually racism, or just that in any given location, black neighboorhoods will tend to have on average lower property values, and thus are cheaper to build the freeway through, but it is disruptive to the community nonetheless.

But he'd never use that example, and I think we all know why.

You won't see me claiming that governments, particularly local and state, don't continue the tradition. This is why black people tend to trust the federal government more and vote for big-government Democrats.

The federal government which gives military hardware and incentivizes the War on Drugs.

And imprisons those very black people that he claims the federal government is going to save.

Well the Philadelphia PD burned down an entire city block that killed a bunch of black people in 1985.

Sorry didn't see you respond due to refresh issues.

Prisons are filled with black people who wouldn't be there if they were white and committed the same crimes.

#Science

Prisons are filled with black people who wouldn't be there if they were white and committed the same crimes

Well, for fuck sake Tony, here you have libertarians pretty much agreeing with you about that, and you prefer to attack libertarians.

I think Rand Paul has your back on that, bro. You gonna vote for him, or Hillary?

Of course, we already know the answer to that, don't we?

Prisons are filled with black people who wouldn't be there if they were white and committed the same crimes.

Except, that's a pretty gross oversimplification. I'd say most of the blacks in prison wouldn't be there if they were upper middle class. I'd also say there is no shortage of poor whites in prison that wouldn't be there if they weren't poor.

You seem to be assuming that prison is a symptom of poverty rather than both being a symptom of something else.

And who put them there?

The very same government who you expect to *save* them.

What's funny is, if we start talking about the exact same thing, only with gender instead of race (the sentencing and conviction bias for males/females is even steeper than for blacks/whites), you would do a complete 180 and proceed to blame the affected group.

So in your example, you're saying that blacks were successful, but that success was cancelled out because white people engaged in actions that were already crimes.

And your solution is for the government to pass new laws, and some how those same racist, white people will have more respect for these new laws and decide to obey them, thus allowing black people to be successful?

No I'm saying we take money from wealthy people and give it to poor people. Conservatives are welcome to continue their strategy of lecturing at them. Doesn't have to be either/or.

I wonder, how many rounds of outright theft of labor and property do blacks have to undergo before we stop prescribing bootstrap therapy?

My bad, I thought we were talking about the same thing.

I thought we were talking about race relations. I didn't realize it was about wealthy people vs. poor people.

People are welcome to stop being such vile racists as well, but I'm not sure how to achieve that except to wait for them to die.

Re: JEP,

See? Stop being such a racist and cough up the dough. In Tony's binary world, you're either a nice, loving and charitable little red Marxian or you're a miserly, raving racist and hoarder of gold coins.

People are welcome to stop being such vile racists as well...

...but that has nothing to do with taking from the rich and giving to the poor.

Re: Tony,

And on and on until the last wealth to be taken is that from the stubborn kulaks.

So you're going to take money from wealthy black people and give it to poor white people?

What do you make of the studies showing non-white immigrants, even from Africa who start with nothing do better than native citizens that start in poverty. Did everyone forget to be racist or something?

It's not so much about present racism as past (though present racism does exist, and in sometimes insidious, institutional ways).

There is always a selection bias present with immigrants who choose to come here. How many poor Africans have the opportunity to immigrate to the US? That higher relative poverty among blacks whose ancestors weren't given that choice still exists can be explained in a couple ways: economic and racist. Curiously, none of the racist arguments entail advocating support for the inherently inferior blacks. Eugenics seems to be just on the tip of the tongue of those arguments.

Re: Tony,

A LOT. There are more opportunities for Africans to migrate from Africa than there is for Mexicans or Central Americans to migrate to the US. That has NOTHING to do with race but with the number of requests filed per year.

Well yes, there's selection bias to a degree. But it in your argument it is race preventing them from excelling. The race didn't change. Now you seem to be suggesting it's not race preventing them from excelling.

So if it's just that immigrants come here and work hard, or take advantage or opportunities, or whatever then the entire plan you've proposed won't work at all because it doesn't address the base reason why some poor people of the same race excel over others.

No I'm saying we take money from wealthy people and give it to poor people.

So that the whites can come in and burn it all down again?

Ok. Let's start with something that you could possibly get libertarians and many conservatives to agree on:

Eliminate agricultural subsidies and corporate welfare for "green energy" boondoggles, and use the savings to eliminate the FICA tax on the first, say, $5000 of annual wage income.

Or, maybe, quit trying to police the world, and us the savings to cut the FICA tax on another $5000 of annual wage income. Do that, and voila, you've just transferred $1530 from the evil rich to every low income wage earner!

Sooner or later you progs are going to have to admit that many of the failures of the black community are the result of aspects of urban African American culture that you not only fail to confront, you actually enable.

The damning evidence of this is that children of immigrants from Africa (who are on average less educated and have poorer English skills than native African Americans) earn more than 'native' African Americans.

Sensible people see that is good evidence that against racism (African immigrants being the same race as African Americans); instead, progs bury it because it implies cultural factors are at play, and the idea that a non-white culture can be anything other than unimpeachable is taboo.

But we don't take money from wealthy people and give it to poor people. We take money from wealthy people and give it to the government.

And the government pays itself, votes itself a pay raise and pays itself again, pays it's cronies and donors for their votes, pays for projects that will benefit their cronies and donors, and then, if there's anything left, they use it to pay for campaigns to raise awareness about how they need to tax the rich more the give money to poor people.

Re: Tony,

Something similar happened 50 years ago in Watts except the black neighborhoods were burned by other blacks. Your point is meaningless.

I give up. How many?

The answer, OM, is blowin' in the wind...

Funny, I thought the answer was at the Tootsie Roll center of a Tootsie Pop...

According to little red Marxian Tony the American black man has suffered from systemic racism for so long, he is bereft of any and all sense of achievement and drive and thus needs the help of paternalistic and charitable white liberals.

No, as has always been the case, brown-skinned people work the hardest and get paid the least. We seem to like that arrangement in this country.

Re: Tony,

How do you know they work the hardest? What is "hardest"? If what you say is true - they are paid the "least" - then borwn people are either very stoic or they're robots.

Don't even attempt to dwell into economics. As has been shown time and time again, you're too incompetent.

Is that why Asians earn more than white people? Why do Asians have an easier time getting mortgages than white people? Must be Asian privilege, right?

Is Tony pretending to be black again? Tony is a skinny white prog boy who pursued the wrong degree and now he's mad at the world because he's too lazy and dishonest to admit that he fucked up and go out and try again. Instead he thinks the government should confiscate your hard earned money and give it him so that he can sit on his ass and drink all day.

How do you know he's skinny?

Hyperion meant "thin skinny"

All young white prog boys are skinny. How else can they get into those skinny jeans, HM?

Drinkin' hot cocoa in his PJ's ...

In his gated community, he won't let us forget about that.

let the black people, wherever possible, however possible, patronize their own kind,

Sure I'm not the first to note this, but isn't this same foolishness as the "buy American!" crowd endorses.

To keep this thread from entering the shitter, as it seems it's going to stick around for a while, here's my recipe for Goat Curry

2 lb goat meat, cut into 1 in cubes

1 lb potatoes, peeled and cut into 1.5 in pieces

.25 tsp turmeric powder

1 tsp hot chilli powder

3 tbsp ground coriander seeds

3 medium onions, chopped or sliced

.5 cup oil

1 tbsp ginger paste

1 tbsp garlic paste

1 tsp garam masala

8 cloves

6 black peppercorns

2 black cardamom pods

Salt to taste

3.5 oz fresh cilantro leaves

Finely chopped green chillies to taste

1 sliced lemon

Heat the oil in a wok or pan. Add the onions and brown them. Then remove the onions with a slotted spoon, grind them to a paste and set them aside. Add the turmeric, chilli powder, garlic, ginger and salt to the oil. Stir-fry for about 3 minutes then add the goat meat and ground onions. Cook until the liquid from the meat dries. Then add about 2 and 2/3 cups water. Bring the mixture to a simmer, cover and cook until the meat is tender. After about 35 minutes add the potatoes and continue cooking until the potatoes are tender and the gravy has thickened to the desired consistency. Transfer to a serving bowl, garnish with coriander, green chillies and lemons and serve with naan.

Have to concede, that is a better response for Tony than my own. Is it any good?

No, it has goat in it.

You crazy.

Mutton. Lamb or goat.

That's a very bold choice. I need to think about this for a while.

I enjoyed your wife's pork bone soup recipe, though.

6 black peppercorns

2 black cardamom pods

What are you, some kind of racist?

Cleveland over the loud objections of the teachers unions and the broader public education establisment.

A particularly loathsome group of racists.

The American black man should be focusing his every effort toward building his own businesses and decent homes for himself.

Racist.

As other ethnic groups have done, let the black people, wherever possible, however possible, patronize their own kind, and start in those ways to build up the black race's ability to do for itself.

Huh, I have been told that even the mere suggestion of these things makes one an unalloyed racist.

Yep. Just as greed means wanting to keep your own money and altruism means spending money that was taken from others, if you suggest blacks can get by on their own you're racist and if you insist they need a helping white hand you support equality.

OT: but slightly more important:

Obamanet

"We respectfully request that FCC leadership immediately release the 332-page Internet regulation plan publicly and allow the American people a reasonable period of not less than 30 days to carefully study it," Republican Commissioners Ajit Pai and Michael O'Rielly said in a statement Monday."

This needs to happen not only for any new regulation that a regulatory agency proposes, but also for every bill that congress votes on or for any executive action that the president wants to use. The most transparent administration in history is going backwards. And 60 days is no way near long enough. 6 months is more like it.

The 3 assholes that want to mover forward with this so that we can find out what is in it, are all Democrats, surprise.

How is this not a blatant example of how Democrats really are worse than Republicans in a lot of ways? The 2 Republicans here are trying to do the right thing by making this new set of proposed rules available for public scrutiny. The 2 Democrats want it passed in the dark. Why, if it's so good, do they need to hide it from the public?

Give it time, the GOP will disappoint.

They do all of the time. That's not my point. On this one very important issue right now, they are trying to do the right thing.

Something tells me that if the roles here were reversed (the Democrats trying to block something the Republicans wanted), you'd see the exact same behavior. One TEAM is trying to stop the other TEAM from doing something, and therefore taking an opposite position. The colors don't matter, the partisan behavior is always the same.

That's why one isn't "worse" than the other, they're both fucking horrible in the extreme, and will prove it to you every chance they get.

If you can show me an example of this this recently where the dems have advocated for transparency and government constraint then I might believe it a little more.

I agree both teams are horrible, but the democrats have recently started to take it an entire new level of horrible.

Of course they have. They're backed into a corner.

This is generally true, but I would argue that Democrats, on balance, have a greater faith and reliance on undemocratic institutions, namely, regulatory agencies.

Fun parlor trick: Walk into a room full of Democrats and Republicans. Start picking completely random regulatory agencies, and say you want to shut them down or even just limit their power. See who squeaks the loudest.

And then start talking about reducing the size of the military or putting vastly greater limits on cops and see who squeaks the loudest.

I think both you and Hyperion are just experiencing Dem fatigue because they have been FULL RETARD for years since Obama was elected. And yeah, they have been completely FULL RETARD and it's really, really bad. So I get it. But if the GOP takes back the White House, get ready for GOP FULL RETARD instead. You'll rediscover your hatred for them too right quick.

I know I will, but that's not for a while. And I'm angry NOW.

Sure. And you'll be angry then too, because they're all the same and they'll continue to fuck all of us.

Honestly, the most ingenious thing the politicians learned to do really well was to turn the whole TEAM thing from a more economic one (Raise taxes! Don't raise taxes!) to an ideological one completely buttressed by KULTUR WAR. The government fucks over people like whoever the Tony sockpuppet is supposed to represent just as much as it fucks over the rest of us. But people like that lap it up because they've been given an ideological reason why them getting fucked too is just peachy. And they slurp it down with gusto.

The politicians have basically gotten a large swath of people to partisanly cheer their own economic and social harm instead of stringing the politicians up on lampposts. It's amazing, and they must shake their heads in contempt for their bases every single fucking day. Probably more like laughing their asses off while going "fucking suckers".

Guys like Justin Amash, Thomas Massie, and Rand Paul give at least some hope to the GOP.

Who is their Democrat equivalent? White Squaw? Bernie Sanders?

There is the one guy, forget his name, that Paul is always trying to work with. But if he's not horrible on economic issues I would be shocked.

Corey Booker, maybe?

Nope, that's not the guy. I can't remember his name...

Patrick Leahy

Fuck off, Leahy!

Alex Lifeson saying "fuck off" justifies that entire series.

What is Rush's guitarist doing on Trailer Park Boys?

Very bad pratfalls and saying "fuck" a lot.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xNJXRbJ8JhM

Wyden

Not that he's good, he just works with Paul sometimes.

Yeah, him too, I forgot.

Jared Polis?

And then start talking about reducing the size of the military or putting vastly greater limits on cops and see who squeaks the loudest.

Yes, you're hunnert percent right. But again, I was focussing on regulatory agencies and their undemocratic nature. Kina ironical for a party that's based on the word "democracy", no?

But if the GOP takes back the White House, get ready for GOP FULL RETARD instead. You'll rediscover your hatred for them too right quick.

Rediscover it? It's sitting right here, idling, ready to go.

"Gentlemen, start your engines! Ready...set...HATE!"

The last GOP POTUS is what caused me to renounce my GOP credentials forever and finally figure out that I am a libertarian and I'm not the only one. Thanks, dubyah.

It was Clinton for me. Complex story. But yeah, Clinton made me go full-glibertarian.

If hate were football, I'd get a flag on the play, every time.

About once a week, I wonder over the FreeRepublic, a rightwing Republican site. They're still full retard when it comes to the military and the whole Team America thing. However, they are starting to recognize that domestic law enforcement has run amok. From my admittedly small sample, they don't seem to blaming it Obama, which is typically their wont.

However, they are starting to recognize that domestic law enforcement has run amok.

I've been saying this for a while now, but when law enforcement loses the dumpy, middle-class white guy constituency, it's over.

The Republicans are giving ground though as a matter of necessity. Paul and Amash are likely the future of that party. The neocons certainly aren't dead, but they're embattled; hell, can you imagine a guy with Rand Paul's foreign policy positions as high up in the GOP ten our twelve years ago?

The dems, on the other hand, seem to be getting worse. They're already about as bad as the GOP on the issues on which the GOP is bad; but they're going downhill in other respects too.

All the delay will do is give the Dems more time to dig up/make up horror stories that occur with the free inaction of human beings online. Eventually I can see them making it illegal to post anonymously on the net.

Eventually I can see them making it illegal to post anonymously on the net

Since this is heavily advocated for on a lot of leftist sites, then I am assuming that this in one of the things that they will try to move forward with. Then they will add 'monitors' to scrub the internet of any posts they don't like and even try to bring hate crime charges against anything they don't like. To achieve this, they will create hundreds of newly funded government agencies, just as they did with Obamacare.

What they essentially want is a Communist China like control of online speech.

The internet is truly the last bastion of freedom. If we lose that, we are looking forward to very dark days.

But at least Comcast won't be able to choke Netflix...

60 Days would work if you also imposed a maximum length on bills.

There should be a maximum length, and also no other unrelated items should ever be allowed in any bill. No more cronybus bills.

It just occurs to me that Clarence Thomas's name can't be mentioned in any circle ever without the subject of racism coming to the front.

This is because the blatant racism of the progs that came to the surface during his confirmation. They really lost their minds when a conservative black man was nominated.

Progs are the vilest people on the planet.

They hate Clarence Thomas because he doesn't paly their game. he doesn't lick their boots and say," Thank you massa for giving me these scraps on the table."

Dude Liberals are the biggest racists out there. Try sitting in a sociology class at a liberal arts school and the discussion when it comes to race reeks of paternalism.

Shit man, I was part of the Republican group on campus and they were nasty towards me because I was black and screamed Uncle Tom constantly.

Tony just called you a racist in an upthread comment. That, despite the fact that I have never seen a comment from you, and I've been here a long time and am here often, that could possibly be construed as racist in any way.

And, this is the same Tony that has openly advocated for 'getting rid of' white people.

That sort of sounds like advocating for genocide to me.

Although what Tony really meant is getting rid of people who don't agree with him politically.

Meet the new left, same as the old left.

It's outrageous how much white liberals hate Clarence Thomas. It's one thing to disagree with his views but he came from abject poverty and became a Supreme Court Justice. That should at the very least garner some respect towards him but instead they spew hateful words towards him.

They hate him because he basically told the white liberal establishment to go fuck themselves and there is nothing they can do about it.

I hate him for his "Lawrence v Texas' opinion. To him police power is unlimited.

To him police power is unlimited

Hillary would agree. Now get down and lick those cankles, buttface, lick em.

He's shillin for Hillary.

He's cuckoo for Hillary.

He's shilling for Hillary.

He plays for the wrong team. Yes, it's sickening how they treat this man.

But the left are also supposed to be champions of the fairer sex, defending women against the right wing war on women. But just look at how they treated Sarah Palin. One of the most disgusting things I have ever seen in all my life.

They also hate him because he did it all by himself, without the help of white liberals.

Arguably, he isn't even a native English speaker. He grew up speaking Gullah.

I'm always amused by upper middle class white proggies knowing more about being poor and black than he does.

It's because they all volunteer to live only in poor all black communities and send their children to those schools.... oh wait...

The funniest part Hyperion is that the very people who lose their shit over school choice are the ones from decent neighborhoods and went to good schools. I guess it's a fuck you, I got mine sort of thing.

You don't need to remind me, EdW, I live among these assholes. There are Obama/Biden stickers all over the Priuses in my neighborhood and I've never seen a more racist bunch of assholes in my life. And I lived in the south in in the 60s and 70s.

I honestly resent assholes like Tony because they have this mindset that black people are children and always will need the guidence of the much more enlightened white people. He doesn't give a shit about black people because they are nothing more the pawns in his mind. Tony's and his ilk's worst nightmare is when black people finally lift themselves out of poverty because they can't use them as props in their quest to create a totalitarian state.

My grandfather grew up during the late 30's and 40's in the Mississippi and you can imagine the bullshit he had to go through as a black man. He had a thrid grade education is pretty much illiterate but he managed to raise 14 children without the government's help and now is retired with too much time on his hands. They basically had to force him to retire at the age of 73. Anyway one day I asked him how did he make it even though things were shitty. He told me that you either survived or you perished. That was it.

He also had a libertarian streak in him even if he didn't know it. The Yazoo and Tallahatchie Rivers flooded and screwed his house up but he refused to except any money from the state or federal goivernment because he said that once you take money from someone without earning it, they own you.

"He told me that you either survived or you perished. That was it."

"...he refused to except any money from the state or federal goivernment because he said that once you take money from someone without earning it, they own you."

That is a man I can respect. My grandfather used a saying that hardly anyone gets anymore: "Back then you had to root-hog or die."

I remember in class I was making an argument against affirmative action and one of the Progs responded that I wouldn't be in college without it. I of course ripped him a new one.

Holy shit.

Clarence on Affirmative Action-

"At least southerners were up front about their bigotry: You knew exactly where they were coming from," he says in the book. "Not so the paternalistic big-city whites who offered you a helping hand so long as you were careful to agree with them, but slapped you down if you started acting as if you didn't know your place."

Amen.

I think it's about social signaling a lot. Most of them don't give a shit about blacks one way or another, but if they say they do then it shows they are caring, loving, right-thinkers. That's why they hate it when blacks disagree with them, it completely shakes their core worldview.

But they're vile because no matter how many times it's shown to them their policies are incredibly patronizing and counterproductive they just don't care. They want to be with the cool kids, and you libertarians are NERDS!

I would argue that they are assholes deep down, and the think they can compensate and pretend they're good people by holding the 'right' opinions and voting the 'right' way. They don't actually have to treat people decently or do anything constructive' just ranting on the Daily Kos about the people they despise is public service enough.

Tony's and his ilk's worst nightmare is when black people finally lift themselves out of poverty because they can't use them as props in their quest to create a totalitarian state.

No worries, they plan ahead, they've already branched out into just about any division of people who are not white males, whom they seem to hate, even though most of them are, in fact, like Tony, white males.

Without the heroic efforts of the progressive left, women, gays, blacks, browns, transsexuals, anyone except for straight white males, would be completely helpless and they need to thank the progs for their place on the government plantation, without which, they would all revert to complete savagery and go back to living in caves.

My Malcolm X favorite quote:

Yes, Malcolm X argued this proposition at the Oxford Union. In December 1964, somewhat after Goldwater said it.

Jon Ronson's articles about the internet are goddamn hilarious.

ButtPig has been exposed as a phony sock puppet. Stop replying to it. It's gearing up to shill for Hillary just to bait everyone here. Don't fall for it, I've already exposed it.

Meet your demise, ButtPig, it's name is Hyperion.

You're an idiot liar. I have repeatedly denounced Hil-Dog.

My preference would be a Brian Schweitzer - Rand Paul matchup.

Hahhahhaaahaaaa, bwwahhhaaahhhaaaa, omg, make it stop, hahahhaaaa, bwaahhhhaaaa, oh it hurts, heeeehehhhhe, wheeeeeheeeeehheeee!!!!

He's shillin for Hillary

He's cuckoo for Hillary

He's shillin for Hillary

Rand Paul, haaahahah!!! OMFG, bwwahaahhahhhaaa!!!!!

Who's your daddy? Say Uncle, bitch, say it!

These are conservative stances on race. Thomas is voicing the conservative position on this--as he did when supporting vouchers.

Today's conservatives do nothing of the sort--though it make look like that to people whose worldview is grounded on the left--including libertarians who come from that direction.

con't

Vocalizing the line about self respect and self responsibility, about self sufficiency and self reliance can sound harsh--doubly so if one is imagining it being said by a white person and directed at black people.

But it is this line that Thomas culls from Malcolm X, the germ of truth in the black muslim movement. Thomas wasn't accepting black nationalism, he was disentangling the basic conservatism that echoes throughout the black community from the dross of quasi-islamic cultism and nascent marxism in which it was buried.

I think the line gets dismissed far to easily when 'conservative' is attached to it. The speed with which it was distanced from 'conservatism' in this article being just one example.

I think this is because there is a reluctance to admit that there is far more classical liberalism lodged under the misnomer 'conservatism' than there is under the even more egregious misnomer 'liberal', and left leaning libertarians don't feel comfortable with that.

my friend's aunt makes $62 an hour on the computer . She has been laid off for five months but last month her pay was $14934 just working on the computer for a few hours. Visit this site.........

????? http://www.work-mill.com