Check Out On Your Own Terms

Suicide among the elderly may be less tragic than self-empowering

Every couple of years, some well-intentioned scribbler pens a hand-wringer about the national tragedy of suicide among the elderly. "Suicide rate for elderly men is alarming," noted Dennis Streets in the Chatham Journal last month. "Suicide rates are high among the elderly," cautioned Paula Span in a 2013 New York Times article. "Elderly are at highest risk for suicide," the AP warned in 2007. Apparently, some of our nation's senior citizens have been deciding for years to check out when they please rather than waiting for the hand of time.

The articles seem to be more human-interest pieces than a response to a pressing concern, since there's been no surge in suicides among the older set in recent years. That 2007 piece cited a suicide rate of 14 per 100,000 among those 65 and older. The CDC's Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System has the latest figure at 14.72 per 100,000 for the same age group. That's down from the 21.8 per 100,000 rate reported in 1987.

The reasons for "suicide are complex and still being researched," a Washington Post piece tutted in December, "but they often include depression." Left unaddressed was one very uncomfortable but important aspect to the story: More so than any other group, the elderly may well have perfectly rational reasons for being depressed—and for choosing to die by their own hand.

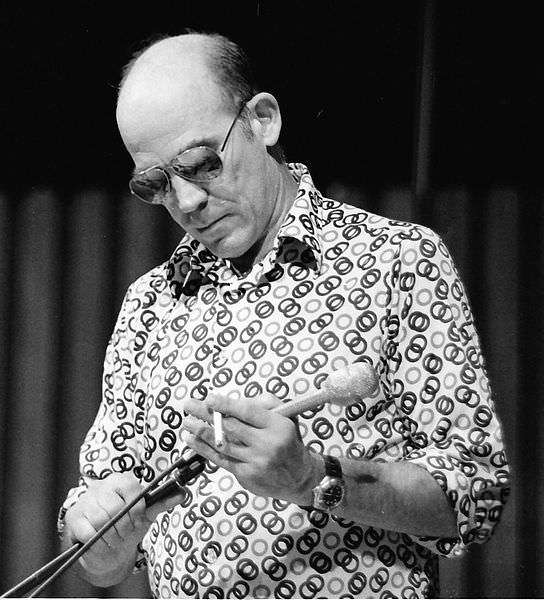

When Hunter S. Thompson shot himself at the age of 67, he was troubled by a failing body and the knowledge that his best writing was behind him. The note he left for his wife read:

Football Season Is Over

No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun -- for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax -- This won't hurt.

Thompson not only ended his pain—he got to go out in style, amidst headlines, with a hell of a party.

Most of us aren't gonzo writers who want to leave with a splash, but even today, when people are living not just longer lives, but healthier ones than their parents and grandparents, there's no escaping the fact that bodies eventually deteriorate. At some point, more than a few people are going to decide that their hearts are still pumping well after the quality of their lives has dropped below a level they find acceptable.

What defines an "acceptable" quality of life varies for each person. Some people are eager to live as many days as possible, others recoil at outliving family and friends, many stop taking pleasure in life when they lose their physical independence, and more than a few may make their peace with declining mobility, but have a horror of mental deterioration that erases the essence of who they are. It's an individual decision that really can't be second-guessed.

Well…It can be second-guessed, of course. "Attitudes and beliefs can be significant factors in suicide, particularly autonomy, dignity, and responsibility," Patrick Arbore, director of the Center for Elderly Suicide Prevention and Grief Related Services Institute on Aging in San Francisco told Today's Geriatric Medicine. Clearly, one person's bug can be another's feature. It depends on your view of death and suicide, and that view can be rooted in very personal feelings.

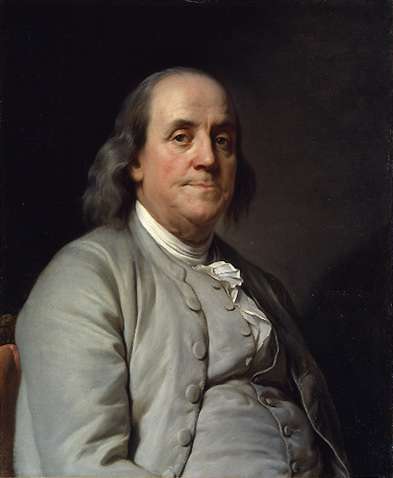

Span's piece for the Times delved into the grief and anger felt by an adult daughter who felt abandoned when her ailing father took his own life. But there's an unavoidable conflict when friends and relatives are unprepared to see us go and we're ready to say goodbye. As he gasped for painful breaths on his deathbed, Benjamin Franklin's daughter, Sally, told him that she wished he would live many years more. "I hope not," he answered.

Grief comes as a natural response to the death of a loved one. So far, death is inevitable at some point, whether naturally or at a time of our choosing.

I have a male relative whose plan for long-term care as he ages consists of ending things when he can no longer care for himself. He's quite clear and matter-of-fact about it, and has held his position for many years. Specifically, when I sat him down to have that simultaneously dutiful and presumptuous conversation about long-term care, he looked at me and said, "I have a .357 Magnum."

My curiosity was as satisfied as it's ever likely to be, and I couldn't fault his choice, though my own preference is a .45. I'm inclined to the same course of action myself, when the time comes. If I'm still up to it those many (I presume) years from now, I think I'll take one last backpacking trip that never ends.

Given that we all must eventually die, the taboo against discussing when and how some of us might want to voluntarily check out can be jarring. It's coming, no matter what; that would seem to be sufficient reason to give some thought to how to confront the end.

"My glioblastoma is going to kill me, and that's out of my control," Brittany Maynard told People magazine in the lead up to her much-publicized death by her own hand (perhaps conscious of the weight carried by the term, she insisted it was not suicide). "I've discussed with many experts how I would die from it, and it's a terrible, terrible way to die. Being able to choose to go with dignity is less terrifying."

If that logic makes sense for a terminally ill 29-year-old, it's no less compelling for other people for whom the end nears one way or another.

That's not to say that every suicidal impulse should be treated as a brilliant idea—such an irreversible act seems especially perverse among the young and healthy. But for people for whom death is a looming reality, the decision by some to slightly adjust the date, place, and manner of their demise can be a rational effort to take control of their ultimate fate and retain a little dignity.

Show Comments (113)