The Latest NSA Revelation Wouldn't Be So Scary If Agency Hadn't Gone Bonkers

How to make a search engine sound terrifying

In other circumstances, a description of the search engine the National Security Agency (NSA) invented in order to comb through data about intelligence targets would be remarkably unremarkable. We would expect the NSA to develop ways to access the intelligence they've gathered efficiently, right? An internal search engine to help government agencies find information they've all gathered about terrorists across the world is just about the right way to respond to the Sept. 11 attacks. Sharing more information between agencies was supposed to be part of the solution.

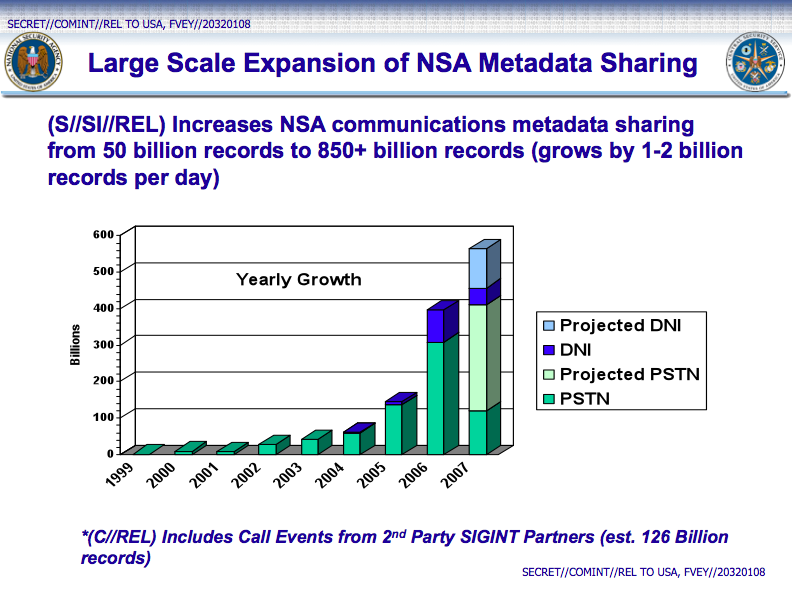

Unfortunately, since that time we've discovered that we are living in a world where the federal government has gathered far, far more information about everybody on the planet, including its own citizens, than we ever conceived. Thus, the latest news story today originating from Edward Snowden's treasure trove of classified documents has a sinister slant that wouldn't have otherwise existed. Today The Intercept detailed the surveillance search engine called ICREACH, which helps more than two dozen federal agencies search through more than 850 billion records about individuals, both foreign and domestic:

The documents provide the first definitive evidence that the NSA has for years made massive amounts of surveillance data directly accessible to domestic law enforcement agencies. Planning documents for ICREACH, as the search engine is called, cite the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Drug Enforcement Administration as key participants.

ICREACH contains information on the private communications of foreigners and, it appears, millions of records on American citizens who have not been accused of any wrongdoing. Details about its existence are contained in the archive of materials provided to The Intercept by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Earlier revelations sourced to the Snowden documents have exposed a multitude of NSA programs for collecting large volumes of communications. The NSA has acknowledged that it shares some of its collected data with domestic agencies like the FBI, but details about the method and scope of its sharing have remained shrouded in secrecy.

The big issue is again what the heck we mean by "metadata." NSA officials and defenders have been downplaying the word ever since Snowden's leaks began, trying to convince us all it's just basic, non-private info. But one of the documents The Intercept has published shows that the NSA has added 25 additional forms of "metadata" past what used to be traditionally accepted: phone numbers called, what time and what length of calls and the like. The new description of metadata includes everything from unique cellphone codes, passport and flight records, visa application records, and cellphone location data.

And then there's the question as to whether this massive expansion in metadata gathering is being used not to fight terrorists but to help secure domestic crime convictions through "parallel construction" processes, secretly sharing this info with local law enforcement agencies:

Parallel construction involves law enforcement agents using information gleaned from covert surveillance, but later covering up their use of that data by creating a new evidence trail that excludes it. This hides the true origin of the investigation from defense lawyers and, on occasion, prosecutors and judges—which means the legality of the evidence that triggered the investigation cannot be challenged in court.

In practice, this could mean that a DEA agent identifies an individual he believes is involved in drug trafficking in the United States on the basis of information stored on ICREACH. The agent begins an investigation but pretends, in his records of the investigation, that the original tip did not come from the secret trove. Last year, Reuters first reported details of parallel construction based on NSA data, linking the practice to a unit known as the Special Operations Division, which Reuters said distributes tips from NSA intercepts and a DEA database known as DICE.

Tampa attorney James Felman, chair of the American Bar Association's criminal justice section, told The Intercept that parallel construction is a "tremendously problematic" tactic because law enforcement agencies "must be honest with courts about where they are getting their information." The ICREACH revelations, he said, "raise the question of whether parallel construction is present in more cases than we had thought. And if that's true, it is deeply disturbing and disappointing."

Read more about ICREACH at The Intercept here and their latest crop of related documents here.

Show Comments (6)