The Financial Crisis of 1837

Trying to understand one of America's great economic downturns

The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis, by Jessica M. Lepler, Cambridge University Press, 337 pages, $29.95

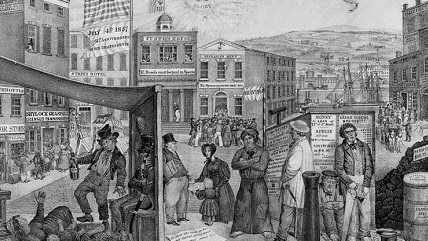

In May 1837, a major financial crisis engulfed America's approximately 800 banks, with all but six ceasing to redeem their banknotes and deposits for specie (gold or silver coins). This was followed by a short but sharp depression, constituting only the second manifestation of the modern business cycle in the country's history up to that point.

The panic had been preceded by President Andrew Jackson's famous "Bank War," in which the Second Bank of the United States lost its exclusive charter from the national government. It was followed by vociferous political disputes about the monetary system, and by a prolonged price deflation that began in 1839 and didn't end until 1844.

Historians and economists continue to explore the panic's causes and consequences, a question made all the more relevant by the financial crisis of 2007-08. Now the University of New Hampshire historian Jessica M. Lepler has entered the fray with The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis, based on her award-winning Brandeis doctoral dissertation. Lepler's book is a social and business micro-history confined to the events leading up to and culminating in the bank suspension. She thus joins the ranks of those cultural historians who over the last decade or so have tried to illuminate topics usually addressed by economists. The result is a work of great detail and mixed quality.

The best feature of The Many Panics of 1837 is the author's prodigious research. Focusing primarily on events in three locations-London, New Orleans, and New York-Lepler combs through such primary sources as Bank of England archives, contemporary newspapers, personal correspondence, sermons, and assorted forgotten books that offered advice on household economy. She exudes familiarity with a vast secondary literature as well, and the footnotes refer to several titles from libertarian authors, among them Lawrence White's Free Banking in Britain, Murray Rothbard's The Panic of 1819, and Richard Timberlake's The Origins of Central Banking in the United States.

Lepler construes the term "panic" in its literal sense to mean an increasing uncertainty and fear, particularly among businessmen, brokers, and bankers. She convincingly argues that not one but multiple panics, arising in each of the three major commercial centers covered, preceded the American bank suspension. Once the suspension took place, it actually had a calming effect on both sides of the Atlantic, she maintains.

These panics were fueled in part by imperfect and delayed communication in an interconnected international market that relied heavily on credit, notably bills of exchange. The failures of major commercial houses in all three cities became the trigger that set off the suspension of specie payments. The Many Panics of 1837 thus reinforces the contention that the subsequent economic downturn was driven as much by events in the United Kingdom as in the United States.

Many historians and economists, by contrast, still place primary blame for the Panic of 1837 on the policies of President Jackson. According to this view, the Second Bank of the U.S. acted as a nascent central bank in restraining the monetary expansion of state banks. As Jackson eliminated the Second Bank's privileges, he unleashed an inflationary boom. Then his Specie Circular of 1836, requiring that payments for public land be made in gold or silver, abruptly cut the boom short and initiated the downturn.

But in the 1960s, George Macesich, Richard Timberlake, Peter Temin, and other economic historians, employing more sophisticated quantitative techniques, began examining the determinants of the domestic money stock. They discovered that the primary factor causing monetary fluctuations during this period was international specie flows, orchestrated largely by the Bank of England. If anything, the Second Bank had encouraged greater use of bank-issued notes and deposits as money rather than keeping a check on state banks. It was therefore the Bank of England, faced with declining reserves, that precipitated the panic by raising its discount rate in 1836.

The deflation that started three years later, after the initial economic recovery of 1838, had a different cause. By this time, specie was again flowing into the United States. A string of outright bank failures (which are more serious than temporary suspensions) drove up both the reserve ratios of the surviving banks and the specie holdings of the general public, causing a collapse of the money stock as large as during the Great Depression from 1929 to 1933 (although the resulting economic distress was nowhere near as severe).

Lepler hardly delves into this period. But she does touch on President Martin Van Buren's proposal for an Independent Treasury, first inspired by the Panic of 1837 and ultimately instituted as a result of these monetary dislocations. Bringing about what was then touted as a "divorce of bank and government"-an explicit invocation of Jefferson's separation of church and State-this reform constituted the first and only time in all of the country's history that the financial system was completely and totally deregulated at the national level. Its full implementation in 1846 also ended the political convulsions over monetary issues, despite the fact that financial deregulation had not extended to the state level.

Unfortunately, Lepler couples her valuable contributions to the literature with some noticeable flaws. Despite her familiarity with several sophisticated economic analyses, she seems to have never mastered the fundamental principles available in more basic economic texts. She states, for example, that banks and brokers attempted to resell bills of exchange for "more than the bill's face value." Perhaps she is using the term "face value" in an idiosyncratic or anachronistic way. More likely, she doesn't understand that bills invariably sold at a discount below face value until maturity. The discount is what varied, usually declining as maturity approached.

This misunderstanding probably contributes to Lepler's scant attention to changes in interest rates when she discusses credit relationships. She instead places most of her emphasis on trust and confidence. Although she does stress how ubiquitous credit was in 19th-century commerce, Lepler never fully grasps its vital role in the allocation of savings. And in her extensive examination of the part that information played in the development and spread of panic, she could have profited from Friedrich Hayek's insight into the role of markets in revealing information. Lepler even believes that economists are oblivious to the obvious, well-known fact that aggregates such as Gross Domestic Product result from "a nearly infinite number of individual choices." These and other lapses lead her to a thinly disguised disdain for economics as a discipline.

The book exhibits some historical lacunae as well. It is undoubtedly a bit churlish to complain that such a well-researched account overlooks some important works. Nonetheless, I was surprised to discover Lepler's reliance on the popular, superficial biography of Van Buren written by Clinton speechwriter Ted Widmer. She never cites Major Wilson's The Presidency of Martin Van Buren, the best book by far not only on Van Buren's presidency but also on the Independent Treasury. If she had consulted it, she would have a deeper understanding of the Jacksonian hard-money program and would have realized that the Independent Treasury was far more profound than a mere alternative to government deposits in those state banks that had suspended. Susan Hoffman's Politics and Banking: Ideas, Public Policy, and the Creation of Financial Institutions would have similarly given her a better perspective on the ideological contours of these monetary debates. Such works might have saved her from her bizarre characterization of the system of state banks-individually chartered by state legislatures, prohibited from interstate branching, and otherwise highly regulated and often subsidized-as a form of laissez faire.

Other flaws arise from Lepler's effort to over-differentiate her product, a vice endemic in academia. Considering The Many Panics of 1837 as more a replacement for earlier studies than a supplement to them, she presumptuously declares that "for political or economic purposes, the panic in 1837 had vanished" from historical accounts until her "rediscovery of the history of panic itself." This is like dismissing a general military history of the Civil War that recounts campaigns, battles, and strategy for not being exclusively devoted to the anecdotal experiences of individual soldiers.

Indeed, Lepler tends to elevate the perceptions of people at the time, which she has documented so well, into reliable and definitive causal explanations of these complex phenomena. One cannot help but be reminded of the fable of the blind men and elephant, except that Lepler has actually seen the entire elephant and still, minutely familiar with one of its legs, adamantly insists that the animal is really a pillar.

While denying that the many panics of 1837 in any way constitute a single event, Lepler does an outstanding job of showing how they are intimately tied together. But while dismissing political interpretations of the panic she simultaneously asserts one of her own: that Jackson's Bank War aroused the anxiety in England that triggered the unraveling of credit relationships. Jackson's actions may have played some minor role, as previous writers have suggested, but it was far from a sole or dominant consideration for Bank of England policies.

While praising the decentralized system of state-chartered banks for their ability to "channel capital into local investments," Lepler nonetheless denounces them because "no single authority determined the policies of political economy." Her overarching conclusion thereby becomes that "the crisis provided a testing ground for different systems of political economy," with the alleged regulatory "protectionism" of the Bank of England outperforming American free trade.

This characterization is off the mark for both countries. Not only does it overlook the extensive state regulation of American banks-and the substantial state subsidies for both banks and internal improvements, which contributed immensely to the panic and subsequent deflation-but it is unduly charitable to the Bank of England and its 1836 bailouts, which hardly brought an end to financial crises in that country. Indeed, a rather severe English crisis that followed in 1847 was hardly noticeable in the U.S., which by then was operating under the complete federal deregulation of the Independent Treasury.

The Many Panics of 1837 is definitely not a book for the general reader. Those not already familiar with the period will find themselves frequently lost or confused by Lepler's grab-bag selection of particulars. Scholars, on the other hand, will find it a superb source of historical details, even if they have to look elsewhere for a compelling or comprehensive integration of these data.

Does the book have anything to teach us about recent economic events? We must be careful to avoid glib generalizations based on superficial or exaggerated parallels; the cause of business cycles remains the great unresolved theoretical problem of macroeconomics. Yet one relevant lesson does apply to both the Panic of 1837 and the financial crisis of 2007-08, a lesson reinforced by Lepler's research: An international crisis invariably involves international causes. Any story that just blames America's domestic monetary institutions and policies, whether for the 1830s or the 2000s, is seriously deficient.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Here's Murray Rothbard's A History of Money and Banking in the United States Before the Twentieth Century

Thanks!

He was a terrible economist as well as a god-awful political theorist.

Oh my, I'm never going to read any more of his books based upon your fact filled comment.

Not sure how interested I am in history so far back.

What I'd like to know is how the current arrangement seems to have left most of the risk at the investor level while pushing the reward up to the banker's level. These days risk seems about the same as it was 25 or 30 years ago but reward is nowhere near the 9 to 12% that was common back then.

I have a number of ideas about how electronic trading has flattened the margins down to whisker thin but it seems the institutions are not giving a whole lot up to the people who bring the cash into the equation.

Let me guess... It was the Fed and quantitative easing.

Hey, AS, why don't you tell us about how great things are going in the glorious people's paradise of Venezuela?

There's a bunch of rich people upset that they can 't pocket more petro dollars like they used to.

Hahahahaha. Yeah, I'm sure all the people with no drinking water are just the rich cronies of the pre-Chavista revolution.

Stupid Venezuelans. Why don't they just willingly die of cancer or dehydration in service to the revolution?

Always remember, Irish, Venezuela, success story, but for being encircled by capitalists.

Cuba in 1959 had the same per capita GDP as Japan.

No, that is why it was short instead of the lingering malaise and gradual withering we are experiencing now.

Actually I came here today to see what kind of knots Richman was tying himself into this sunday....so far nothing. He must have had a brain-freeze at his keyboard.

He must have had a brain-freeze at his keyboard.

I blame Israel.

For someone who comes across as such an avowed socialist and devout Marxist, Why spend your time on a free-market libertarian website?

You sit back and fire off an old cliche socialist argument(that we all know failed) then you subsequently get hammered for it with superior arguments.

It's like watching a 5 year old (AS being the 5 year old) debating theoretical physics with Albert Einstein.

Did you forget about the Second bank of the US? Or do you just choose to blatantly ignore monetary history and the debauchery of money? Oh wait, it didn't say federal reserve, and facts simply can not support your argument.....so just ignore them. You could go back further and research how the Romans debased the Denarius and the troubles that caused....nah but to hell with that, you can advocate your socialism based upon myths and all the failures of such a violent system throughout history....oh and wait, go on to call yourself compassionate.

An international crisis invariably involves international causes. Any story that just blames America's domestic monetary institutions and policies, whether for the 1830s or the 2000s, is seriously deficient.

What?

So Fanny and Freddie had nothing to do with it?

Are you fucking kidding me?

If you meant this seriously, I think the important word in the passage you quoted is "just". If you were being sarcastic, then disregard.

JC, to blame an international financial crisis solely on a non-world power America (1837) is dubious.

Yes, the 2008 crisis, in my opinion may lay more with American financial policy. However, to look at Europe's endemic welfare state corruption and debt-based government operations as non-contributing is also dubious.

So Fanny and Freddie had nothing to do with it?

Are you fucking kidding me?

Necro alert, but you're reading the issue wrong. It's not that Fannie/Freddy didn't have anything to do with it, it's that their collective impact is overstated.

Hennessey, Holtz-Eakin, and Thomas's dissent from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission fleshes this idea out a bit further. The other Dissent (Wallison's) goes in-depth with just how much of an impact Fannie/Freddie may have had.

The distortions in the business cycle between 1803 and 1850 had to do with the digestion of the Louisiana Purchase - cycles of boom and bust for decades. Of course a little bad government policy and proto-cronyism certainly helped. We know the boundary because it was around 1850 that we had to turn to settling Northern and Southern borders. The real question is what extra cronyism made 1837 particularly worse.

its awesome,,, Start working at home with Google. It's a great work at home opportunity. Just work for few hours. I earn up to $100 a day. I can't believe how easy it was once I tried it out. http://www.Fox81.com

It was theoretically resolved by the time of Von Mises. All that remains unresolved is the root cause of the cycle; the state.

The root cause of the cycle is a sudden influx of money into a monetary system. It can occur without state intervention, even in a monetary system that utilizes full reserve banking, as has happened due precious metal rushes. The best defense against it is to completely separate saving and investment within the banking system so as to prevent contagion when investments firms begin bankrupting due to malinvestments.

Are we hinting at a Glass Steagal solution? If only there were a system which would only punish overleveraged banks and leave the others alone.

That's what happened with the Spanish economy after they pillaged the Aztecs but that in no way is an explanation of the modern business cycle.

A system-wide downturn is not the result of millions of decentralized actors voluntarily trading at mutually agreed upon terms. The only way a systemic downturn comes into being is with a system-wide catalyst. The only such catalysts are central banks and regulatory regimes. If your thesis were valid, the business cycle's existence wouldn't happen to coincide with the rise of state banks and hyper-regulation.

Not at all. The best defense is stop perverting incentives, to stop creating moral hazards. If the investment banks that made bad decisions weren't receiving politically funded rewards for their bad decisions, they wouldn't make such decisions.

And so what if the savings and investment banks aren't separated? Why don't other countries without a Glass-Steigel type of statute face the same outcome? Canada wholly lacks such a law for instance.

I was thinking more about the Bank of Amsterdam. Central banking systems contain feedback mechanisms which tend to cause the rapid expansion of the money supply which causes problems similar to those that occur during precious metal rushes. I never said it was an explanation, it is the root cause though.

'Business cycles' have been occurring for thousands of years. A few unusually productive harvests and people begin to think it will continue indefinitely such that they reduce their savings and are less concerned about capital destruction. A bad season hits and they're fucked. Historically, states have absolutely made the situation worse, but their full explanation goes beyond the state.

I was not referring to Glass-Steigel regulation, which has little to no effect. I was talking about a full reserve banking system, where loans would be handled by wholly separate investment firms. It's imperative that people understand that putting money in a fractional reserve bank is not saving, it's investing. It carries risk which should be assumed by the investor(no fdic) and it would be wise to choose a firm on the basis of it's loan portfolio, not the arbitrary reasons people currently choose banks. So I agree with you, the best defense is to stop perverting incentives and to stop creating moral hazards.

Unlike government fiat, precious metals are finite. It's government fiat's near unlimited ability to expand the monetary supply that is the root. And we certainly can't ignore the regulatory regimes that help cause the moral hazards that provide incentives to market actors to be unscrupulous with other people's money, like in '08.

Booms and busts have indeed happened for a long time. But not at regular intervals we see today and not nearly as dramatic or long lasting as the one's we endure today. Bubbles in the past were the result of emergent events, not necessarily an inevitability within a given amount of time. System-wide events have a system-wide cause, and if we exclude natural disasters and such, the only institution capable of inducing a persistent system-wide deficiency are political institutions.

Perhaps I'm wrong in my reading of your text here but it seems to me that you're arguing that the boom and bust cycle is itself a feature of free markets. A feature of people creating and voluntarily exchanging value. This argument would imply that we need a mafia to coerce those marketplace participants to not fuckover every other marketplace participant. When in fact the market itself contains such regulating mechanisms and it's the mafia that creates these "market failures" with their corrosive interference.

I can't say I disagree here. Aside from burying your money in the back yard, virtually anywhere you park your money should be viewed as an investment. Especially in this age dominated by inflation.

In the past, I think banks were best suited to deliver that product but overtime as the ad-hoc patchwork of regulation has been heaped on the industry, this has changed. It's the same reason why credit unions have become so much more attractive over the past few years, they're exempt from most of the rules governing financial institutions in the Federal Reserve System. We'll see more species of financial holding companies come into existence.

OMFG. Rothbard, and many other Austrian economists (Sanchez, Philbin, etc.) have covered this and many other economic events throughout history already. The business cycle was already figured out and explained by Mises among many others.

The socialists and Keynesians still can't grasp such am explanation, not because it is hard to learn, rather it is because they don't face consequences for the theft, and violence they advocate as they are shielded by politicians.

Trask (etc.) dealt with Temins 1969 works that many held on to for a while. Why this is being made into some "new discovery is nonsensical. It's all there to read....all that was needed was a little research.

Well Keynesians and their school of thought weren't created to discover truths of economics, they were created to provide and intellectual excuse for fascist policies.

There are many "ists" that can be attached to Keynesian economics. Hate to be repetitive (maybe it will finally sink in one of their effing heads) but the policies of John Law put Keynes to bed before him and his latter followers were born. There are many other examples as to why such policies, and economic interventions are ludicrous.

I don't toss the various -ist's around lightly. Don't take me for one of those "You're a fascist, maaaaan!" types. I mean to say Progressivism is an intellectual descendant of 20th century fascism. A bunch of liberals who decided they sort of liked markets but not as much as they liked dictators with unbridled power. FDR for instance, was a big fan of Mussolini and in the early years of Nazi propaganda they bragged about ideological kinship they shared with American progressives and New Deal policies.

I am not taking you for anything! You're supposed to be taking MEEE for burgers.

financial crisis engulfed America's approximately 800 banks