D-Day's Anniversary

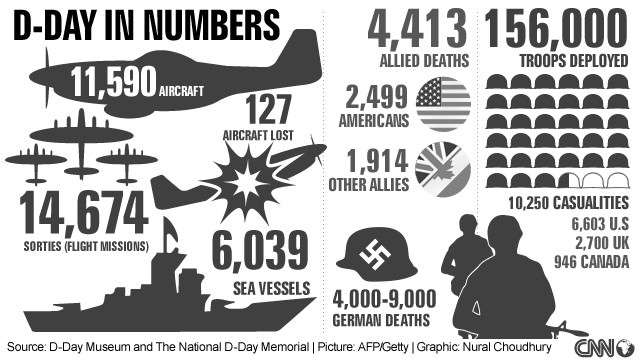

Today marks the anniversary of D-Day, the invasion of Normandy by U.S., British, Canadian, and other allies in World War II.

The full Normandy campaign lasted through August and by the time it was over, it was clear that the Germans were pretty much done for.

By the end of the Normandy campaign the Germans were hemorrhaging men and machines, with two armies all but destroyed. True, a handful of Germans did escape the attempted encirclement around Falaise, but it was still a massive Allied victory. In the rapid advance that followed, the Allies moved more quickly than Germans had in the opposite direction four years before, during the invasion of France.

Last fall, British artists produced a genuinely fascinating and moving project on the beaches of Normandy by sand-sculpting 9,000 bodies to commemorate the fallen:

A wider shot:

My father participated in the Normandy campaign and last summer my sons and I visited the area, which really drives home the immensity of the undertaking and the sheer ballsiness of it all. Would that there was no need for an American cemetery there. But one of the most striking things about it is the incredibly diverse set of names, religions, and states on the grave markers there. You take any five or 10 crosses and there will be three religions; Irish, German, Italian, Jewish, and Lebanese names; and not just different states but different parts of the country altogether.

In 1999, Thomas W. Hazlett commemorated D-Day in Reason with a column about how the ad hoc nature of the invasion once it was under way demonstrated the value of a Hayekian approach to local knowledge and decentralized decision-making. The Allied plans went wrong in a thousand different ways but the American troops had the flexibility and the authority to improvise.

Perhaps the classic demonstration was the landing on Utah Beach at 6:30 a.m.—the first wave. Due to unexpectedly strong tides, landing craft deposited units over 1,000 meters from their pre-arranged positions. Heavy machine gun fire pinned down those who managed to survive long enough to reach the beach. Crouching for cover, U.S. infantrymen assembled and spread out their maps. They had no radio contact, and most of their commanders could not be located. What the hell to do? Should they get down the beach to where they were supposed to be, or attack the German artillery directly in front of them?

The ranking officer quickly made a decision: "Let's start the war from here." With that, brave Americans charged Nazi fortifications straight ahead, knocked out guns, scaled the bluff, and circled around to capture the ground they had originally been assigned to take.

While no lowly soldier in the Wehrmacht had the authority to revamp official orders, the Allied invasion consisted of little besides ad hoc heroism. Decentralized information stormed the beaches on June 6, 1944, and irreparably breached the Atlantic Wall by dusk. Pretty good theory for one day's work. Pretty good work for one day's theory.

Show Comments (84)