The Sultan of Sewers

William Burroughs' anti-authoritarian vision.

Call Me Burroughs: A Life, by Barry Miles, Twelve, 718 pages, $32

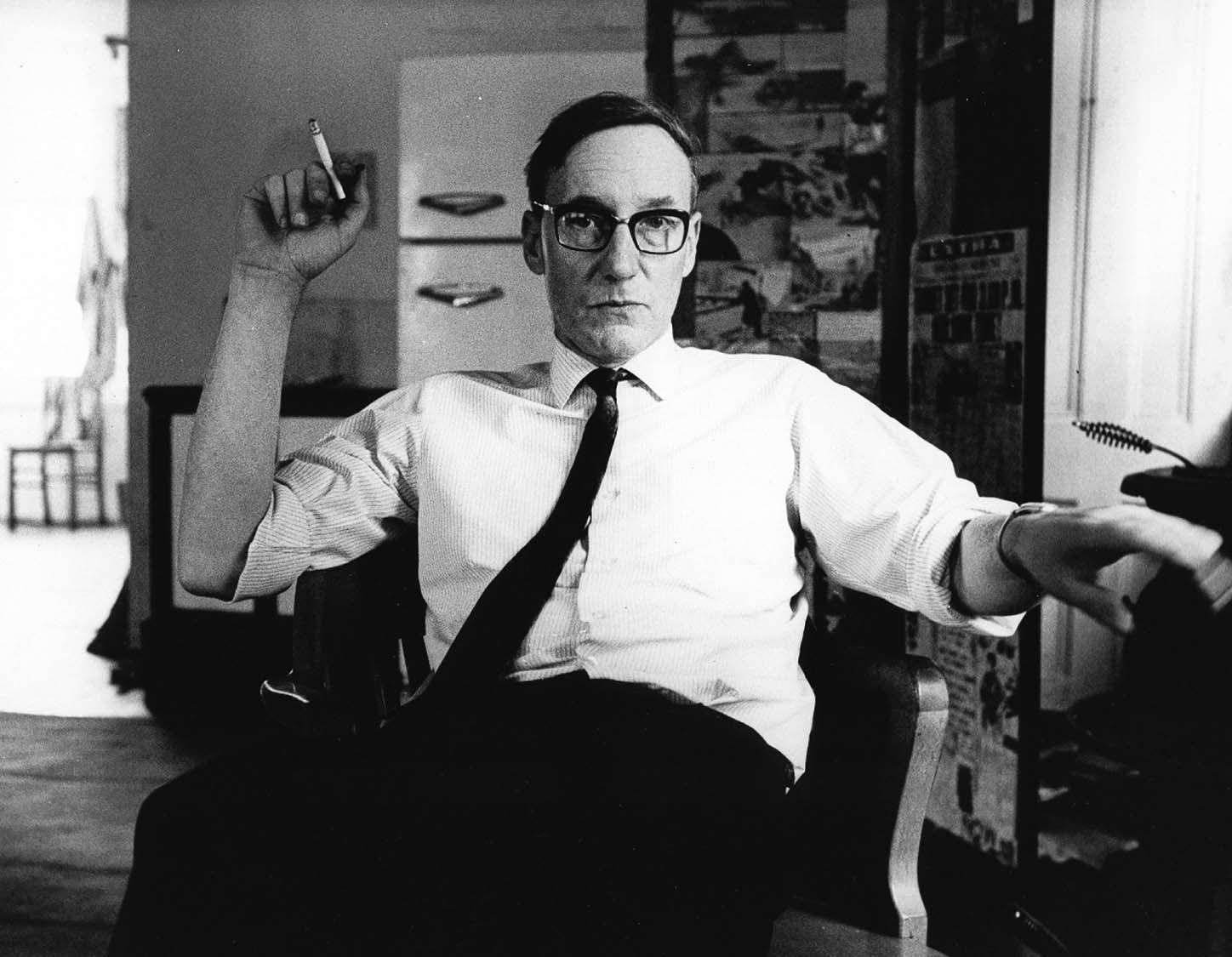

In July of 1957, an unknown writer named William Burroughs visited a friend in Copenhagen. After three weeks in the area, including a brief excursion to Sweden, he wrote to the poet Allen Ginsberg that "Scandinavia exceeds my most ghastly imaginations." In Naked Lunch, the novel Burroughs was writing at the time, Scandinavia became a model for a place called Freeland. "Freeland was a welfare state," the book explained. "If a citizen wanted anything from a load of bone meal to a sexual partner some department was ready to offer effective aid. The threat implicit in this enveloping benevolence stifled the concept of rebellion."

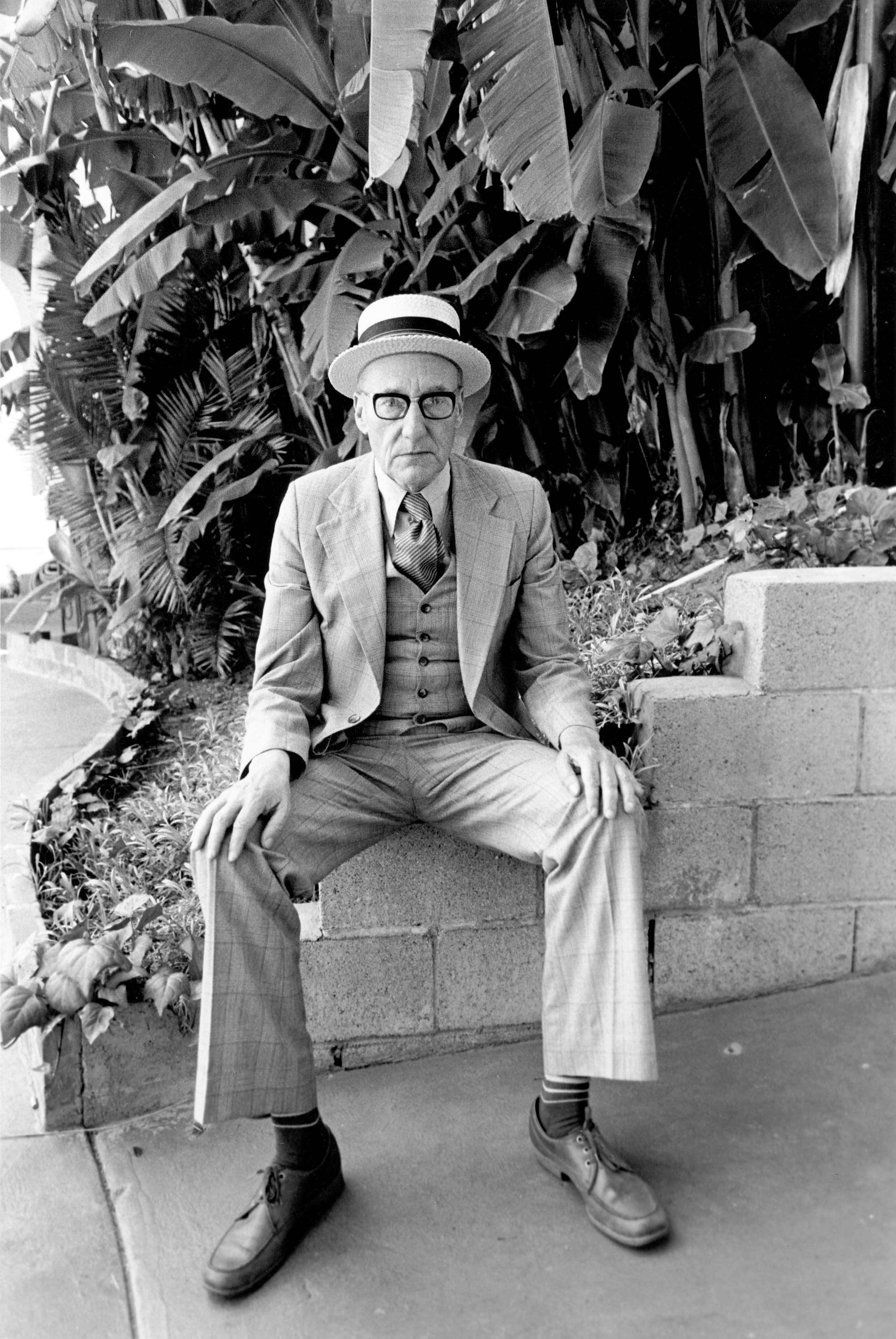

After Naked Lunch was published in 1959, Burroughs graduated from unknown writer to literary celebrity. Today he is widely regarded, along with Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, as one of the three towering figures of the Beat movement. He was one of the most prominent figures in the emergence of the postwar counterculture, and his influence stretches well beyond the Beats to the bohemias of the '60s, the '70s, and beyond. In 2014, a century after his birth in St. Louis, his work remains a touchstone for alienated cynics of all kinds.

But Burroughs' worldview was miles from the peace-and-love socialism that our cultural clichés tell us to expect from a hippie hero. In 1949, according to Barry Miles' new biography Call Me Burroughs, he complained to Kerouac that "we are bogged down in this octopus of bureaucratic socialism." When he was a landlord in New Orleans he sent Ginsberg a rant against rent control, and when he found himself owning a farm in Texas he gave Ginsberg an earful about the evils of the minimum wage. Eventually he departed for Mexico, and there he wrote to Ginsberg again. "I am not able to share your enthusiasm for the deplorable conditions which obtain in the U.S. at this time," he told his leftist friend. "I think the U.S. is heading in the direction of a Socialistic police state similar to England, and not too different from Russia….At least Mexico is no obscenity 'Welfare' State, and the more I see of this country the better I like it. It is really possible to relax here where nobody tries to mind your business for you." He added that Westbrook Pegler, a hard-right pundit who would soon be a vocal defender of Sen. Joe McCarthy, was "the only columnist, in my opinion, who possesses a grain of integrity."

Two decades later, covering the Democratic Party's bloody 1968 convention for Esquire, Burroughs manifested a more left-wing aura. A day after his arrival he donned a McCarthy button—the antiwar insurgent candidate Eugene McCarthy, that is, not Pegler's pal Joe. When cops started assaulting protesters outside the convention hall, Burroughs immediately aligned himself with the radicals in the streets, declaring in a public statement that the "police acted in the manner of their species" and asking, "Is there not a municipal ordinance that vicious dogs be muzzled and controlled?" He then helped lead an illegal march that ran straight into a contingent of cops and National Guardsmen.

In doing this, he was not merely supporting the protesters' civil liberties. He was aligning himself with one side of what he saw as a grand conflict. "This is a revolution," he wrote in a 1970 article for the East Village Other, "and the middle will get the squeeze until there are no neutrals there." Still later in his life, he would identify "American capitalism" as his foe, specifying: "the American Tycoon…William Randolph Hearst, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, that whole stratum of American acquisitive evil. Monopolistic, acquisitive evil."

So had the aging artist shifted from the far right to the far left? Not exactly. Burroughs' hostility to the police was a constant throughout his career. In that same letter to Ginsberg that praised Mexico for not being a welfare state, he added this nugget: "Here a cop is on the level of a street-car conductor. He knows his place and stays there." And when Kerouac's 1957 novel On the Road described a lightly fictionalized version of Burroughs, it declared: "His chief hate was Washington bureaucracy; second to that, liberals; then cops." The hostility to corporate monopolies had been there in the early years too, with Burroughs displaying a particular fondness for conspiracy tales in which big business suppresses inventions that threaten the bottom line. And the young Burroughs' hatred of the New Deal liberals who held power in North America didn't keep him from embracing the anti-feudal, anti-imperial liberals he encountered in South America. In Colombia he even gave his gun to a guerrilla boy. "Always a pushover for a just cause and a pretty face," he wrote to Ginsberg in 1953. "Wouldn't surprise me if I end up with the Liberal guerrillas."

In later years, conversely, he still didn't have much praise for the federal government. In The Job—Daniel Odier's book of interviews with Burroughs, published in various forms between 1969 and 1974—the novelist denounced the income tax ("These laws benefit those who are already rich") and allowed what began as a rant about money to evolve into an attack on inflation. ("Money is like junk. A dose that fixes you on Monday won't fix you on Friday. We are being swept with vertiginous speed into a worldwide inflation comparable to what happened in Germany after World War I.") When Odier inquired about the assassination of Sen. Robert Kennedy, Burroughs began his answer with the sort of conspiracy theory you might expect from a hip '60s liberal—"It seems likely that the assassination was arranged by the far right"—but then veered in a different direction, declaring that "the arrangers are now taking this opportunity to pass anti-gun laws, and disarm the nation for the fascist takeover." On the rare occasion that Burroughs did manage to say something nice about the feds, he still couched his comments in libertarian language. In 1982, when Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine asked him how he felt about the space program, he replied that it was "practically the only expenditure I don't begrudge the government."

Burroughs was no conventional conservative. As a bisexual, a drug user, and a writer whose work was regularly damned as "obscene," he came to regard the right as a gang of bigots and busybodies. But he was no conventional radical either. His anti-authoritarian vision cut across the normal categories of left and right. "At the present time," he said in The Job, "we are all confined in concentration camps called nations. We are forced to obey laws to which we have not consented, and to pay exorbitant taxes to maintain the prisons in which we are confined." As an alternative, he called for consensual communities that "break down national borders."

* * *

Burroughs' influences ranged from Pegler to the ultra-left Situationist International, but the most important early source for his worldview was a man not normally thought of as a political writer at all. Jack Black was a former hobo and burglar whose memoir You Can't Win engrossed the teenaged Burroughs, leaving a lasting impact on both his outlook and his literary voice. (Black's first publication, a newspaper serial titled "The Big Break at Folsom," was ghostwritten by a young reporter named Rose Wilder Lane, who would later play a formative role in the American libertarian movement.) It was Black's description of an underground code—and his scattered references to the beggars and outlaws who embraced that code as an extended "Johnson Family"—that gave Burroughs' rebellious streak an ideological framework.

A Johnson "just minds his own business of staying alive and thinks that what other people do is other people's business," Burroughs wrote in his 1985 book The Adding Machine. "Yes, this world would be a pretty easy and pleasant place to live in if everybody could just mind his own business and let others do the same. But a wise old black faggot said to me years ago: 'Some people are shits, darling.'" In 1988, penning a preface for a reprint of Black's book, Burroughs offered this account of the world's core conflict: "A basic split between shits and Johnsons has emerged."

The Johnsons took center stage in my favorite of Burroughs' novels, a surreal sci-fi western from 1983 called The Place of Dead Roads. The book's hero is an Old West outlaw who dreams of "a Johnson Family takeover. He will set up a base in New York. He will organize the Johnsons in Civilian Defense Units. He will oust the Mafia. He will buy a newspaper to push Johnson Policy, to oppose any further encroachment of Washington bureaucrats. He intends to strangle the FDA in its cradle, to defeat any legislation aimed at outlawing liquor, drugs, gambling, private sexual behavior or the possession of firearms." This being a Burroughs book, the Johnsons find themselves in conflict with a control system far larger than any government: a "prerecorded universe." So they set out to "tamper with the prerecordings."

Another revolutionary fantasy opens Burroughs' 1981 novel Cities of the Red Night. Here again the heroes are outlaws. Burroughs had discovered the legend of Captain Misson, a probably-fictional pirate whose self-governing, freedom-loving crew was said to have targeted slave ships, liberating the cargo and inviting them to join Misson's buccaneers as equals. According to legend, they eventually established an anarchistic colony on Madagascar called Libertatia. Burroughs imagines an alternate history where Libertatia survived and inspired imitations. "Imagine a number of such fortified positions all through South America and the West Indies, stretching from Africa to Madagascar and Malaya and the East Indies, all offering refuge to fugitives from slavery and oppression," Burroughs writes. "Imagine such a movement on a world-wide scale. Faced by the actual practice of freedom, the French and American revolutions would be forced to stand by their words. The disastrous results of uncontrolled industrialization would also be curtailed, since factory workers and slum dwellers from the cities would seek refuge in [the pirate colonies]. Any man would have the right to settle in any area of his choosing. The land would belong to those who used it. No white-man boss, no Pukka Sahib, no Patrons, no colonists."

In a sense this was a new Burroughs: The onetime landlord and employer was now dreaming of a world without landlords or bosses. But the mechanism he imagined didn't resemble the rent-control and minimum-wage laws he denounced in the '40s. If anything, he was calling for something even more anti-statist. Burroughs didn't want a bureaucracy; he wanted a world without control systems.

When Burroughs discussed control systems, he frequently deployed the metaphor of addiction. When people mix the rhetoric of addiction with the rhetoric of liberty, they often end up calling for restrictions on freedom in the name of freedom. There is a long history, for example, of Prohibitionists defending anti-alcohol laws on the grounds that they liberate us from the "slavery of drink." But Burroughs didn't take that path.

Consider his most famous statement on the subject of addiction. From 1962 onward, Naked Lunch has included an introductory essay that tells us that drug addicts live in a state of "total possession," that they are "sick people who cannot act other than what they do." This needs to change, Burroughs announces: "The junk virus is public health problem number one of the world today" (italics in original). This is precisely the sort of language you often hear from supporters of the war on drugs.

These words came in the context of Burroughs' struggles with the censors—there were several attempts to stop the book from circulating, culminating in a famous obscenity trial in 1965—and it's easy to read his preface as a way to show the speech police that the book has redeeming social value. ("Since Naked Lunch treats this health problem," it states, "it is necessarily brutal, obscene and disgusting.") Even so, it contains nuances that undercut the impression that the novel is an anti-drug cautionary tale. When Burroughs uses the phrase "junk virus," the literary scholar Timothy Melley notes in Empire of Conspiracy (2000), "it is never quite clear whether this term refers to addictive drugs themselves or the larger drug economy in which they move." And the way to undermine that drug economy, Burroughs explicitly writes, is to allow people legal access to morphine rather than letting pushers monopolize it.

In the 1991 edition of the book, Burroughs added an "afterthought" to the preface that stood the Prohibitionists' rhetoric on its head. "When I say 'the junk virus is public health problem number one in the world today,'" he wrote, "I refer not just to the actual ill effects of opiates upon the individual's health (which, in cases of controlled dosages, may be minimal), but also to the hysteria that drug use often occasions in populaces who are prepared by the media and narcotics officials for a hysterical reaction." He goes on to state that the drug problem began with prohibition and that the anti-drug panic "poses a deadly threat to personal freedoms and due-process protections of the law everywhere."

For Burroughs, the word addiction applied to far more than just drugs. The world's rulers, notably, were addicted to power. "Is Control controlled by its need to control?" he wrote in Ah Pook Is Here (1979). "Answer: Yes."

* * *

Miles' biography is one of those doorstops full of details that may be diverting for readers already interested in the subject but aren't likely to engross anyone else. Virtually every available fact about Burroughs' life is here, from his favorite sexual position to what he liked to eat for breakfast. Where a firm fact isn't available, we get well-documented speculations. Being a Burroughs fan myself, I enjoyed it, to the extent that it's possible to enjoy a book that paints such an unflattering portrait of a writer whose work I admire. The fact that Miles clearly likes Burroughs and is doing his best to put a positive spin on things just makes the effect worse.

Burroughs was the spoiled scion of a wealthy family—his grandfather, also named William Burroughs, had invented the adding machine—and he received a monthly allowance from his parents until he was 50. (The resulting mix of dependence and resentment may have influenced his ideas about the stifling benevolence of welfare.) With that money to cushion him, he was able to drift from one short-term job or business venture to another. He dabbled in petty crime, for a brief period even teaming up with a junkie buddy to roll drunks. Under Jack Black's spell, the young Burroughs romanticized the criminal life; it wasn't until the '50s that he came around to condemning crimes against persons and property, distinguishing them from acts that are illegal but victimless. "And I used to admire gangsters. Good God," he told Ginsberg.

His irresponsibility reached its zenith in Mexico on September 6, 1951, when a drunken Burroughs announced that he and his wife would demonstrate their "William Tell act." She then placed a whiskey glass on her head, and he tried to shoot it off. The bullet hit her forehead instead, and she died. It was the worst of the bad things Burroughs did in his life, but it wasn't the last: The homicidal spouse went on to be a neglectful father too. By Miles' account, he was also a neglectful employer, handing over the day-to-day operation of that farm he briefly owned to managers who treated the laborers poorly. (He claimed to Ginsberg that he was working on a profit-sharing plan, but Miles doubts that anything came of it.)

The book sheds light on the less appealing parts of Burroughs' worldview as well as the less appealing parts of his life. There was an ugly current of misogyny in his work. There was that early indifference to violent crime. And his attempts to evade control systems sometimes led him down bizarre paths, some of them excessively rationalist and some irrationalist.

On the rationalist side, his suspicion of tradition led him to flirt with ideas like a new calendar devised from scratch. (He saw the old calendar, in Miles' words, as "an obvious control system accepted unthinkingly by everyone.") On the irrationalist side…oh, where to begin? Burroughs was fascinated with fringe science and the occult. He "often took tabloid reports seriously," Miles reports, "particularly if they were of a pseudoscientific nature." He engaged in pseudoscientific speculations of his own as well, and not just in his fiction. In that interview with Asimov's, he followed up his kind words for NASA with a strange complaint that the agency was sending people into space in an "aqualung" instead of "effecting biological alterations in the human structure that would make it more suited to space conditions." When the interviewer countered that we'd still need oxygen, Burroughs replied: "Well, that's what we say, but there's no prerequisite."

Burroughs' obsession with fringe science even led him to an interest in Scientology, which occupied much of his attention for a period in the 1960s. He was turned off by the sect's authoritarian atmosphere, and he eventually denounced its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, as a fascist. ("Scientology is a model control system," he wrote in Rolling Stone. With Burroughs, remember, "control system" is always a term of abuse.) But he also believed that many of Hubbard's techniques really worked. While other people attacked Scientology for spreading pseudoscience, Burroughs attacked it for trying to maintain a monopoly on its scientific discoveries.

* * *

Burroughs was a criminal before he denounced crime, an addict before he denounced addiction, a Scientologist before he denounced Scientology. It's a core part of his persona: He exuded the air of someone who's been there, who's made mistakes, who's been a shit as well as a Johnson. Burroughs often affected the pose of an old con letting the marks in on how a confidence game is done. If he seemed at times to be indicting himself along with everyone else, well, he deserved it and he knew it.

In 1975, Harper's posed a question to an assortment of public figures: "When did you stop wanting to be president?" The respondents were an odd collection: former presidential candidate George Romney, future president Ronald Reagan, JFK hagiographer Ted Sorensen, and so on, with Bill Burroughs dropped into the middle of them. "I never wanted to be President," he answered. "This innate decision was confirmed when I became literate and saw the President pawing babies and spouting bullshit." This was not, he continued, a matter of "youthful idealism." It's just that Burroughs' ambitions were "of a humbler and less conspicuous caliber. I hoped at one time to become commissioner of sewers for St. Louis County—$300 a month, with the possibility of getting one's shitty paws deep into a slush fund."

A long fantasy follows of his life in office: blackmailing the governor, leaning on the sheriff for the drugs he's confiscated ("he'd better play ball or I will route a sewer through his front yard"), assembling a personal goon squad ("handsome youths, languid and vicious as reptiles, described in the press as no more than minions, lackeys, and bodyguards to His Majesty the Sultan of Sewers"). The essay becomes a fever dream of grimy grandeur: "Let kings and Presidents keep the limelight. I prefer a whiff of coal gas as the sewers rupture for miles around—I have made a deal on the piping which has bought me a $30,000 home, and there is talk in the press of sex cults and orgies, carried out in the stink of what made them possible. Fluttering from the roof of my ranch-style house, over my mint and marijuana, Old Glory floats lazily in the tainted breeze."

It's a great riff, funny on the page and even funnier if you hear a recording of Burroughs reading it aloud in his dry Midwestern tone. And it ends with Burroughs returning not just to the question about the presidency but to his old theme of addiction and control, though he doesn't use those terms this time. "What would you do if you were in the President's place?" he asks. "You would be inexorably pressured by the forces and the individuals that made you President, and by your own desire to be President in the first place; so you would wind up doing just what they all have done." Burroughs' line about dope addicts—"sick people who cannot act other than what they do"—turns out to apply to power addicts as well. Control is controlled by its need to control.

Like many satirists, Burroughs here takes on the role he's mocking, lacerating his target by playing an exaggerated version of the part. But it isn't entirely a role. To expose corruption, Burroughs exposed a corrupt place in his soul.

Around the same time Burroughs was sending Ginsberg letters from Mexico about the evils of big government, he learned that he could get a generous GI Bill subsidy if he enrolled in the Mexico City College School of Higher Studies. He didn't hesitate to sign up, and in a letter to Kerouac he didn't hesitate to speak frankly, self-mockingly, about his monetary motive. "I always say," wrote the Sultan of Sewers, "keep your snout in the public trough."

Show Comments (39)