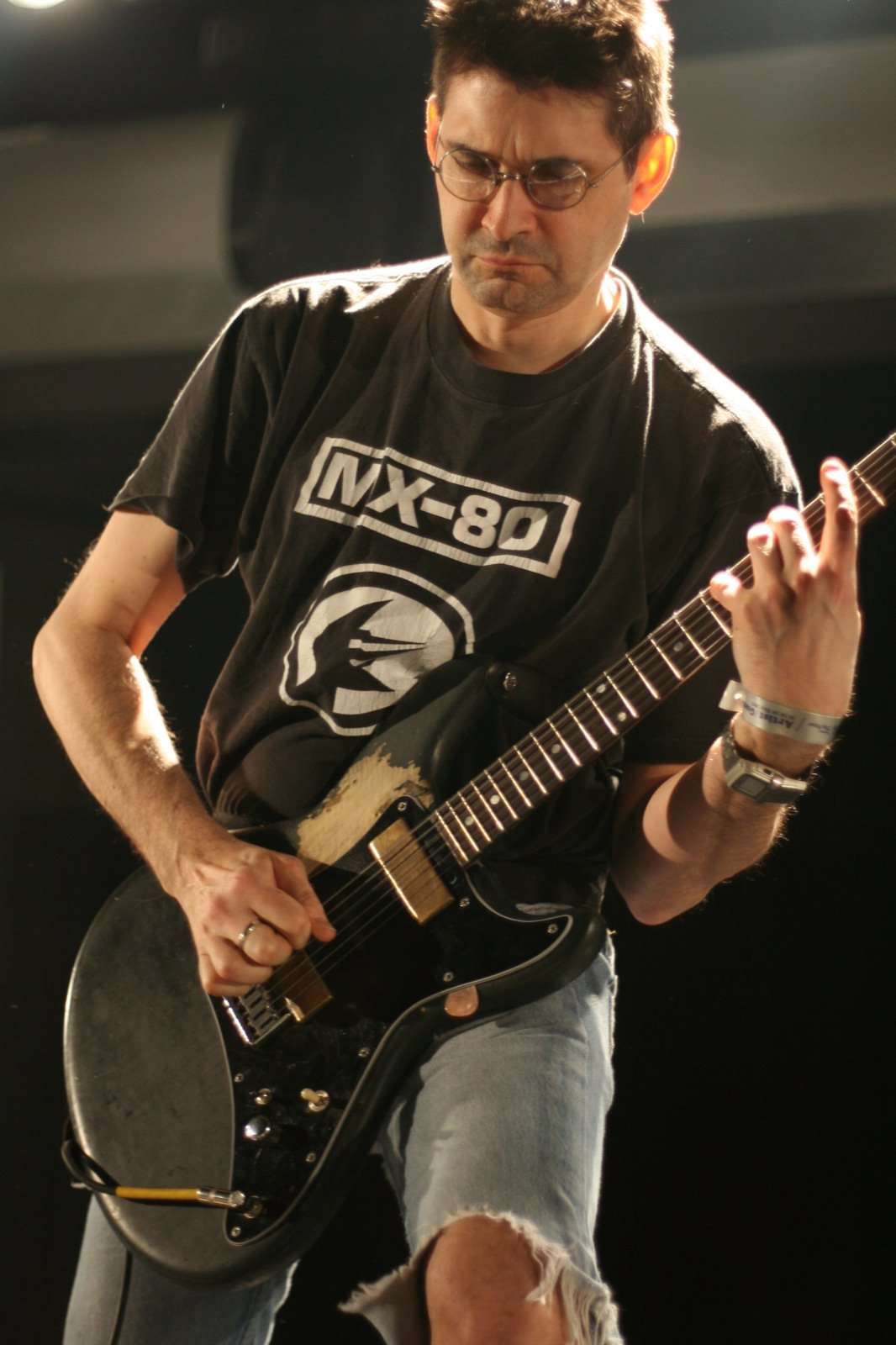

Legendary Punk Producer Steve Albini Says the Internet Solved the Problem With Music

Those of you old enough to remember when the word "grunge" described both a genre of music and an "alternative" lifestyle choice may remember an influential Baffler essay by rock producer Steve Albini, "The Problem With Music." You can read the whole thing online here, but the gist was a sort of punk-radical, anti-corporate argument that the entire music industry was set up to benefit everyone—the studios and the scouts, the image consultants and video makers, the lawyers and managers—except the fans and the musicians. Thanks to the complex structure of recording contracts, bands with huge deals could come out of the process making essentially nothing, or in some cases technically in debt.

This was an essay that people interested in the alternative music scene talked about for years afterwards—it was published in 1994, but I don't think I heard about it until the late 1990s—because it seemed to capture and diagram the slimy, stupid awfulness of the generic, corporate-captured music that dominated the era. Not only that, it came at an unusual time for the punk/alternative community. The big labels appeared to be handing out zillion-dollar record contracts to punk and indie-rock bands with roughly the same sort of attitude that one throws parade candy into a crowd. Garage bands with six songs and three shows under their belt were being shown big dollar signs, snapped up, and pushed through the corporate-music grinder, or at least that's what it felt like. There was a big debate within the scene about what constituted selling out, and whether it was a good thing or a bad thing. This was all informed by punk's longstanding suspicion of commercially successful art and corporate culture. It was a scene where the most common stage move for a frontman was to turn his back on the audience and look at this shoes. It was all very angsty and introspective. People wore a lot of flannel.

Albini's essay made such a big impact in part because was arguing that you could sell out—and still manage to not get paid. Which was about as strong an argument against selling out and going mainstream as one could imagine. And, of course, Albini's credibility on the subject was more or less unimpeachable, because, as we used to say, he'd been there and done that. Albini was Kurt Cobain's choice to produce Nirvana's final studio album, In Utero, which was made to sound dirtier, noisier, and, well, grungier than the slick rock sound Butch Vig had given the band's breakout record, Nevermind.

I note all this because Albini recently returned to the ideas of his famous essay in a brief interview with the online magazine Quartz. Somewhat surprisingly, Albini, who was typically pretty consistent for his music-business pessimism, is now rather upbeat, even as many in the music industry have become increasingly pessimistic.

"The single best thing that has happened in my lifetime in music, after punk rock, is being able to share music, globally for free," he told Quartz. Here's a bit from the piece:

"Record labels, which used to have complete control, are essentially irrelevant ," he says. "The process of a band exposing itself to the world is extremely democratic and there are no barriers. Music is no longer a commodity, it's an environment, or atmospheric element. Consumers have much more choice and you see people indulging in the specificity of their tastes dramatically more. They only bother with music they like."

In the physical music era, company executives and the music press were the arbiters of taste—a band needed to convince a label to sign it, fund it, and often get critics to like it, to have a realistic shot at success. These days, it's a much more meritocratic process: people can make music in their garage and reach their audiences through YouTube, BandCamp and any number of internet avenues. "You can literally have a worldwide audience for your music….with no corporate participation, which is tremendous," Albini says.

I think Albini's right that the Internet has positively changed music culture, and allowed for strange niches to develop and individuals to explore and connect with what they like. I used to spend weeks or months hunting down certain albums, hoping for a chance to hear some obscure band from across the country that I'd heard about at a show. Touring bands would travel with bins full of tapes, and eventually blank CDs, copying and trading interesting new music from local artists at every tour stop. When a new band would come into town, suddenly you'd find new music being passed around. But the process of diffusion was pretty slow. It could be weeks before anything new or interesting popped up again.

That doesn't really happen anymore, because everyone has heard everything already. Practically anything anyone wants to hear is already there, on the Internet. The concept of "alternative" music basically doesn't exist anymore. There's just the music that people like.

The Internet killed corporate music. But it also killed the corporate music business model. The downside, then, is that the old revenue mechanisms are gone (or at least significantly diminished) too.

It's hard for even fairly successful rock artists to support themselves these days. At best, selling music ends up being a loss leader for live shows and other revenue streams. But that only works in a limited number of cases. Concert tickets, even at higher prices, don't make up for nearly as much revenue as the overall industry has lost.

What keeps me hopeful, though, is that there's still a lot of great new music being made. And it's easier for fans to access, and artists to break out, than ever. Nor is it as if it were ever easy to make big bucks playing rock-n-roll. As Albini's original essay made clear, it's always been hard for artists to succeed financially, even with the old money-making mechanisms in place. It still is. But the Internet (along with cheap, high-quality home recording technology) has changed the focus of the industry from discovery and distribution to the music itself. Overall, that's a good thing.

This post has been updated for clarity.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Wasn't the early 1990s when Brian Doherty was in the punk band industry? Interested on his take on this.

The music "industry" has sucked since the advent of the compact disc.

Yeah, reel-to-reel was the pinnacle of music distribution technology!

You're not to far off the mark. I blame digital recording and production.

And the loudness war.

The main issue with CD's is that since there is no extra mfg cost to releasing a 75-minute album vs. a 33-minute album, artists stopped editing themselves and released far too many records that were 70% filler.

The only genre improved by CD is classical.

I ran an indie record label, yes. And for my own purposes, I stopped exactly as the digital transition was being made---mostly out of an entrprenurial laziness in trying to figure out how to navigate that brave new world. But Albini is of course self-evidently correct: it is easier for more bands to try to find an audience. The brief historical bubble when musicians could reliably make a living selling recorded music may have seemed like "the way the world is" if you were born in the 60s or before, but it ain't the way the world is anymore.

While it doesn't mention Albini per se, I wrote a Reason cover feature in the antediluvian era about how selling out wasn't necessarily the way to strike it rich in indie culture:

http://reason.com/archives/199.....-of-riches

Cool.

Brian, if you don't mind mentioning it, can you name some of the artists you worked with?

Sure. I can almost guarantee you've never heard of any of them! The Jeffersons (my band), Fluffy Kitty, Weinix, Meringue, Big Swifty, Vacation Bible School, Action Suits (Peter Bagge's then-band), Hazeldine (only one who went on to the "majors" with one lp on Polydor, Europe only!), Harry Pussy

That's pretty rad. I actually have been meaning to listen to Harry Pussy - just listened to an interview of Patrick Flegel from Women and he mentioned them.

I lost a fair amount of money doing it, but not crippling by any means. Nothing sold more than 1,800 or so units on my end, most below 500. I wasn't very good at it, whatever being good at it was supposed to mean, except I thought the music was all very good.

the Internet (and cheap, high-quality home recording technology) has changed the focus of the industry from discovery and distribution to the music itself. Overall, that's a good thing.

Don't you mean "again"? Until the 1950s the music industry was based on sales of sheet music.

Yep, the "sell recordings to make a living" model was a bizarre and in retrospect brief historical outlier in mankind's relationship with music...

That's where the publishing scam began. Which is why publishers make huge coin off radio play in the US and the internet streamers have to pay mechanical royalties while radio does not.

For the 10 people interested in the music promotion business, this is a good book:

http://www.amazon.com/Pennies-.....rom+heaven

I mostly agree with Albini here, but there are two minor sticking points:

1) Albini doesn't know what "democratic" means. He seems to think it means "everyone gets their own way", but that's not democracy. Democracy is majority rule. If 49% vote for certain bands/labels/genres to get their money, and 51% vote for OTHER bands/labels/genres to get their money, guess who gets the money? The ones the 51% voted for, while the ones the 49% voted for don't. Democracy is majority rule, not everyone gets their way. This isn't democracy. This is BETTER than democracy.

2) Albini doesn't know what a "commodity" is. A commodity is just a marketable item. Is music in the digital age no longer marketable or marketed? No. It still is, it's just not up to a privileged, well-established, and legally backed set of special interest groups (e.g. the RIAA).

The problems he's been so upset with aren't really the fault of the type of business structure that's been involved (the corporation), it's because of the legal backing (*cough*government*cough*) the interest groups have had. Legal backing that is no longer enough.

You are right about the legal backing. It's amazing how much pull J.P. Sousa had in shaping IP law regarding music, and of course he was a government employee so he had a lot of pull.

i took an entertainment law course once and my professor said you'd be surprised how many broke rockstars there were because they were always in debt to the label for the record costs and touring costs. I think you have to make it pretty big to be financially secure as a musician -- maybe Metallica big or some other equivalent. The ability to record a quality record at home using a computer and post it on iTunes is a pretty cool thing. However, because we now have so much music and other content out there, it's easier to miss something that is actually good which is kind of frustrating.

I still mainly rely on radio for new music. I don't have the time or inclination to wade through the piles of junk out there to find the good stuff. Radio DJ's are payed to find good stuff so I rely on them and then pick and choose what I personally enjoy from what they play.

The app Shazam I think has done more for finding music than anything I can think of. There have been countless times that I have heard a song playing somewhere and Shazamed it to find out what it was.

Unless your listening to stuff off the top-40/easy listening/oldies channels that's exactly *not* what the DJ's job is.

Those guys are paid to play the shit ClearChannel tells them to play - its the execs at ClearChannel who are looking for new music to fill those lists with, not the DJ's.

Maybe on Top 40 stations. There are a lot of stations that don't play top 40 though.

Most stations cap their current playlists at 100 songs, and will have no more than 1,500 (and that would be large) in their 'library'. What market are you in with terrestrial radio so outside the norm?

That is the one thing about radio these days - the stations in small markets now sound more adventurous than the large market stations. 25 years ago it was the exact opposite.

Radio DJ's are payed to find good stuff

Nope.

The few radio DJ who are allowed to put what they want on the air are almost all volunteers. The few who get paid are doing someting else for an actual living.

On the other hand - its easier to find the one or two things a small band puts out that are good rather than having pushed on us the mediocre shit that forms a good chunk of really big band's output.

In the past, a Madonna or Metallica put out a record with 3 or 4 really awesome songs and a lot of filler and that's all you got.

Nowadays you can dump the filler and find the good shit that tons of one-hit wonders put out.

Creedence Clearwater Revival are probably the poster boys for broke rock stars. They were badly screwed by their record contract.

Or Badfinger- broke and dead.

Legendary? Dude made every artist he produced sound exactly the same. I guess that's a skill...sorta.

Listen to Nirvana's "In Utero" and Slint's "Spiderland" and get back to us.

I actually like the sound of his recordings, but yeah, he gets a lot of credit for essentially just not miking everything ridiculously close.

Plus, when comparing the Nirvana albums, Butch Vig is a drummer and Albini is a guitar player so they kind of have personal biases on how they wanted the instruments to sound that is always reflected in how their production jobs sound.

My #1 complaint about Led Zeppelin is that Jimmy Page always made the drums sound like shite.

Cobain had a baffling double personality when it came to the producers he chose.

On one hand, he was disappointed by the slickness that Vig and Andy Wallace had given Nevermind. On the other hand, he liked the lo-fi quality of In Utero, but complained that the drums and vocals were too quiet in the mix.

I think Vig's genius was locking down Grohl on the drum beat. The band was all over the place when they recorded Lithium. Vig eventually had to force Grohl to use a click track. But it produced a suitable recording.

Also, tricking Cobain into doing multiple takes so that he could layer the takes was a genius move. Drain You alone has about a dozen guitar and vocal tracks, and it is the best track on the album. Vig pushed this tactic to the extreme on the Pumpkins' Siamese Dream, arguably his best work.

"Touring bands would travel with bins full of tapes, and eventually blank CDs, copying and trading interesting new music from local artists at every tour stop."

Really? I never heard of any band doing this ever. Are you sure they weren't just dumping the unwanted demo tapes handed to them by kids at the previous show? Because that I've seen.

there's still a lot of great new music being made

More like a little bit by a handful of Scandinavians

What, Dude I never heard of such a thing.

http://www.myAnon.tk

I disagree with Albini on one point- the relevance of labels. Going way back, indie labels were a sort of curator. Take an SST or Alternative Tentacles. You heard of Black Flag and Dead Kennedys, liked what you heard. You wanted more. Where did you turn? Those labels put their catalogs inside their records. Buying a Black Flag record gave you access to the Minutemen, Husker Du, Meat Puppets. A Dead Kennedys record gave you access to the Crucifucks, BGK, or TSOL. I bought records from several labels just on the strength of association.

This is still possible today, and labels like Joyful Noise and Outer Battery do this. Small labels that cultivate particular sounds or scenes are as relevant as ever- maybe more now than ever. The other side of everything being out there is that there is a lot to wade through to get directly to the sounds that will please.

When no one buys music, the funds to buy studio time dry up, and this is exactly what has happened. A young band (or a not so famous old band) is lucky if it ever gets to see the inside of a real studio these days.

Record labels did bad things, sure, but they also did good things, e.g. provided the budgets for studio recordings, many of the same ones that spotify and its ilk now collect money on with only token compensation to the artists. These records would not exist were it not for these budgets. On the small to middling scale, this just doesn't happen anymore, because it can't.

There's no use complaining about it, because it is the way it is and it's not going to change. The reality of the market is that a song is worth just about zero dollars now. But it's a bit rich for people who achieved fame and fortune under the old system to celebrate this fact. No matter what people say about the wonders of laptop technology, you can't record a rock and roll album in your bedroom (I mean, Radiohead probably can in their country estate or whatever, but you probably can't.) It's harder now, a lot harder. That's just the way it is, but it's no reason to celebrate.

Sun Records studio was about the size of a small bedroom.

Was it actually a bedroom, though?

For the particular world I was working in, indie-hipster rock, yes those would have been exceptional successes, though of course in the "major label" world, dismal failures.

The 1997 feature I linked to in my first comment has more specifics about the economics of the 90s pre-digital business model.

those would have been exceptional successes, though of course in the "major label" world, dismal failures.

Bud and Miller will generally quickly cancel a new brand that "only" sells 500k bbls in a year.

That is larger than the entire brewery output but all of a small handful of craft breweries.

And about 1000x my 2014 target.