If the U.S. Is Going to Have Dynasties, at Least Have Good Ones

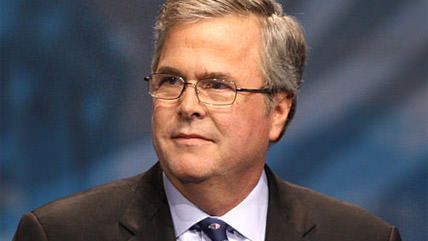

The push for Jeb Bush.

Draft Bush! That's the GOP establishment's bold new scheme for 2016.

And people say they're out of ideas.

"Many if not most" of 2012 nominee Mitt Romney's biggest donors are courting former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, the Washington Post reported Sunday; the "vast majority" would back him in a nomination fight, according to one top fundraiser. Jeb, brother and son to presidents 43 and 41, respectively, hasn't yet made up his mind: "the decision will be based on ?Can I do it joyfully?'"

If he can, he's stranger than he seems, and maybe not the sort of fellow we want to trust with nuclear weapons.

Still, Jeb seemed pretty jubilant last fall, at a Philadelphia event, where he and Hillary Clinton, the odds-on favorite for the Democratic nod in 2016, "basked in a mood of bipartisan bonhomie." Bush was there to give his potential 2016 rival the National Constitution Center's "Liberty Medal." "Hillary and I come from different political parties, and we disagree about a few things," he joked, "but we do agree on the wisdom of the American people -- especially those in Iowa and New Hampshireand South Carolina."

Bundlers are loose in the realm; the battle for the throne is shaping up as House Bush vs. House Clinton, and winter is coming. Oh joy.

In America, any child "may become president, and I suppose it's just one of the risks he takes," two-time Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson once cracked. But we run a bigger risk of getting someone with a famous last name. Since I became aware of politics, sometime around the start of the Iranian hostage crisis, either a Bush or a Clinton has been on a major-party presidential ticket in all but the last two races; 2016 would make it eight out of ten. And consider the irony that one of the main figures standing athwart another Bush-Clinton race is Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., himself the scion of a minor political dynasty.

The Founders wisely barred the federal government from granting "titles of nobility" (though they may have been too quick to dismiss "corruption of blood" as grounds for political disqualification). Still, they recognized that "there is a natural aristocracy among men," as Thomas Jefferson put it to John Adams in 1813, "the grounds of this are virtue and talents."

Neither Jeb nor Hillary, one suspects, is quite what Jefferson had in mind. Like his brother "43," Jeb is given to anti-Jeffersonian tropes about the dangers of "neo-isolationism" and "American passivity" in foreign policy. Hillary thinks it's the president's job to be "commander in chief of our economy," and she's rarely met a war she didn't like, including the Iraq debacle, which she voted for before she was against it.

Alas, political dynasties are hardly a new development in American life. They may even be unavoidable: some intriguing recent research focusing on the prevalence of certain surnames in high-status positions suggests as much.

It may be that the best we can do is what Adam Bellow calls "meritocratic nepotism," an ideal that balances "the privileges of birth" with "the iron rule of merit": connections can get you the job, but you'd better not screw it up.

If so, then we shouldn't look for Kennedys and Roosevelts, Bushes and Clintons to fill the presidency. Whatever its faults, the Harrison presidential dynasty, William Henry (nine) and grandson Benjamin (23), did less damage than its more-famous rivals: "Tippecanoe" barely lasted a month after his interminable Inaugural Address. And the Tafts — President William Howard (our 31st) and son Robert as a senator — resisted the 20th century drive toward imperial presidencies.

If nepotism's our fate, we should go for better nepots.

This column originally appeared in the Washington Examiner.

Show Comments (93)