Mitt Romney Was Right, and Wrong, About Russia

Barack Obama and John Kerry might be just wrong

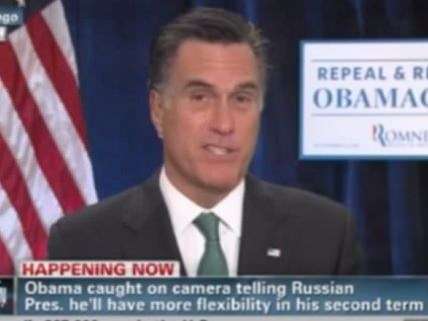

During the 2012 campaign, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney called Russia America's "number one geopolitical foe," an observation that yielded him ridicule from his Democrat detractors. Then-Senator John Kerry made a joke about Romney living in the world of Rocky IV, a comment the Obama campaign even turned into a "movie poster." In 2014, John Kerry, now the secretary of state, has resorted to having to tell Russian President Vladmir Putin that when it comes to Ukraine "this is not Rocky IV." So was Mitt Romney right? Yes and no.

Russia's projection of military power into Crimea after pro-European protesters in Kiev and around Ukraine succeeded in spurring a change of government is certainly the action of a geopolitical power. On March 1, Putin asked for and got from parliament authorization to use military force in Crimea. President Obama called Putin, among several other world leaders, and, according to a statement from the Kremlin, Putin "drew his attention" to ultranationalists he said were supported by the government in Kiev, and "stressed" Russia retained its right to protect its interests in eastern Ukraine.

Since then, Russia has taken effective military control of that part of Ukraine, though the soldiers there are unmarked and Russia insists they're local "self-defense" groups from the ethnic Russian population in the region. The Russian government has also reportedly encouraged veterans to holiday in Crimea. On Thursday, the pro-Russian regional government in Crimea voted to join Russia, with a popular referendum to follow in ten days. President Obama condemned the vote as being against the Ukrainian Constitution and international laws. Obama insists the world is "beyond the days when borders can be redrawn over the heads of democratic leaders," though the actions by Russia and the government in Crimea would appear to indicate otherwise. Russia doesn't recognize the government in Kiev, either, calling it the result of a coup.

Crimea became a part of the Ukraine in 1954, when Nikita Khrushchev, upon succeeding Joseph Stalin as leader of the Soviet Union, transferred it from the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian one. Khrushchev, in fact, was Stalin's man in the Ukraine before the outbreak of hostilities between the previously allied Nazis and Soviets during World War II. Russia, the successor state to the Soviet Union, still considers World War II a defining event in its development as not just a geopolitical power but a global one. And Russia's history as a regional/continental power, of course, extends hundreds of years before that. Wars like the Crimean War in the 19th century were fought between Russia and Western powers looking to contain it, in that specific case while the Russian Empire was seeking to expand into the space left by a waning Ottoman Empire. Russia's bloody and brutal 80-year-long experiment with Communism helped position it as one of just two super powers in the second half of the 20th century, while the final collapse of the Soviet Union created an opportunity for nations long held by some form of Russian empire to use their nominally semi-autonomous SSR status to break free.

Mitt Romney was right: Russia is a geopolitical power, maybe even a foe. Romney's underlying assumptions, that it's our foe, is wrong. The protests in Ukraine started because the country's president, Viktor Yanukovych, who has since stepped down from power and been charged with mass murder, pulled back from talks with Europe in favor of closer ties with Russia.

Some of President Obama's domestic critics may point to Russia's actions in Ukraine as a result of perceived weakness, but that's not really how international affairs work. More importantly, the U.S. isn't relevant in Ukraine. Europe, on the other hand, may be, and certainly wants to be. The eastern countries of the European Union (EU), having spent much of their history as buffer states similar to the Ukraine, are understandably worried about Russia's actions. The EU risks becoming a buffer super-state. So far, it has threatened to call off certain talks with Russia, like over visa liberalization, in response. It can offer little more. While Eurocrats in Brussels spent the last two decades building a political infrastructure and bureaucracy for their super-state, they rely almost exclusively on the American security umbrella for their defense needs. In this way, for much of Europe, too, World War II remains a defining moment—one when the business of spending on military force shifted to the United States.

That didn't change at the end of the Cold War either. U.S. military spending slowed in the '90s, but while the EU worked out a Common Security and Defense Policy, it didn't seek to replace the U.S. military presence on the continent, instead continuing to rely on the U.S. and NATO for its defense needs. Concurrently, it turned increasingly to Russia and its gas, and pipelines running through Ukraine, for its energy needs. Russia, then, may be a geopolitical force, but it's not in Europe's interest for it to be a geopolitical foe. Neither is it in Europe's interest for the U.S. to be involved, even though it may welcome Kerry at ongoing negotiations over Ukraine being held in Paris.

The U.S. may be imposing limited sanctions now, but it's highly unlikely to commit to any military engagement over Ukraine. As Steve Chapman noted this week, even those Obama critics proposing a "stronger" reaction to Russia's involvement in Ukraine aren't offering much more than the Obama administration has—largely diplomatic tools like more sanctions and other economic threats. It would be better for the U.S. to do nothing. Just a few weeks ago, the Pentagon announced plans to reduce the size of the army, an acknowledgement of the need to have a smaller military footprint. That smaller military footprint has to come with a smaller diplomatic one. The Ukraine crisis is Ukraine's alone to solve. Geopolitics may draw Russia and the EU in, but they should keep the U.S. out. Though President Obama and John Kerry may wish the world were a post-geopolitical one, their desires don't make it so.

That said, it may be a Rocky IV world, but it's not our fight.

Show Comments (83)