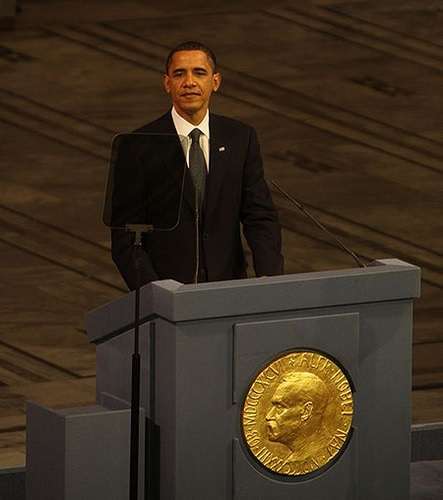

What is President Obama Thinking About With a Military Intervention in Syria?

Is he?

For more than two years, Syria has been embroiled in a civil war. It began when the long-time regime of Bashar Assad (handed down to him from his Ba'athist father, Hafez Assad) tried to quell uprisings in the country pinned to the Arab Spring and spiraled into a full-fledged armed conflict. American interventionists like John McCain have been pushing for US involvement in Syria since 2011. The Obama Administration took a relatively more subdued approach, though President Obama had already said Assad "had to go" back in 2011. That declaration, however, wasn't backed by any kind of real support, and instead had the effect of cutting off the idea of engagement as a solution to an issue the US foreign policy establishment believes is relevant to them.

Eventually, Obama laid down a "red line," the use of chemical weapons. In April, Israel said it was "nearly 100% certain" the Syrian regime had used chemical weapons, but Chuck Hagel wasn't so sure. The next day, Hagel said U.S. intelligence sources had "some degree of varying confidence" Assad had in fact used chemical weapons. Obama said a "line was crossed," but that more "direct evidence" was needed. Eventually, Israel hit what the Free Syrian Army said was a chemical weapons facility. Then, all still this April, Obama moved the goal posts to the "systematic" use of chemical weapons. Iran helpfully agreed that the use of chemical weapons (they, of course, meant by rebels, who the Syrian regime accused) would be crossing a line. But Western (and Iranian, too) intervention in Syria had already begun. By June, the White House said it had confirmed the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime, and announced it would be providing Syrian rebels with military aid.

In this month's apparent chemical weapons attack, the Obama Administration is signaling its intent for a more forceful punitive response. The White House insists it's not seeking regime change (but it already acknowledged that's what it was looking for years ago), but to send a message that chemical weapons use is unacceptable. Here's the way one official put it to the LA Times:

[H]e believed the White House would seek a level of intensity "just muscular enough not to get mocked" but not so devastating that it would prompt a response from Syrian allies Iran and Russia.

"They are looking at what is just enough to mean something, just enough to be more than symbolic," he said.

A phone call to Tehran or even Moscow would ensure a response that was "more than symbolic" without risking the life and limb of whoever the US might decide to point cruise missiles at in retaliation for the use of chemical weapons. Despite the insistence of interventionists to "do something," no one in the US foreign policy establishment has articulated anything close to a strategic interest in intervention. The former Congressman Dennis Kucinich, on the other hand, has been able to articulate a very clear strategic interest in non-intervention: intervention would make the US akin to "Al Qaeda's air force," and even trigger a world war by making a unilateral move in a multilateral conflict. Kucinich zeroed in on the strategic interest that was inherent in not intervening similarly in Libya two years ago; Al Qaeda today has a far stronger presence in the country than it did under Col. Qaddafi (when it was nearly non-existent), and tens of thousands of surface-to-air missiles (and other weaponry) went missing after the US intervention.

Foreign Policy's Stephen Walt sees Obama as being dragged reluctantly into the Syria conflict by a desire not to appear to be damaging US credibility by drawing red lines that can be crossed without a whim. Walt writes that the notion of Obama lacking credibility on the use of force is "especially silly" given the president's history of the use of force in places like Afghanistan, Libya, and in the drone campaign. But credibility isn't just about the use of force. It's about engagement. And while Obama's foreign policy has been heavily interventionist, it has avoided engagement. Together, it makes for a sometimes aimless but highly destructive foreign policy. Obama, for example, "escalated" in Afghanistan, as Walt writes, but he did not use the fruits of that escalation to attempt to broker a peace or negotiate an exit. He let the moment come and pass, and is still dithering on a withdrawal, unwilling to commit to it, but unwilling, also, to engage anyone else about it.

And so it is with Syria, where President Obama and his advisors believe lobbing cruise missiles, without the authorization of Congress and or even an understanding of what would happen next, is more palpable than engaging the other sides involved. Or even imagining that the conflict in Syria might not need any kind of American involvement, and that regional powers, even including in Europe, were free enough to handle it on their own.

Show Comments (197)