8 Reasons Not to Go to War in Syria

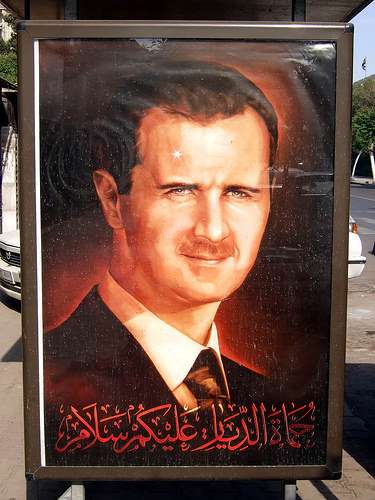

Is the U.S. on the march to war in Syria? Over the past week, the stage has been set for yet another military intervention in the Middle East. Calls for U.S. action in Syria have grown louder following reports of a chemical weapon attack in Damascus said to have been carried out with the knowledge and approval of President Bassar al-Assad's regime. In the past few days, hawkish rhetoric has grown increasingly aggressive, and additional reports today indicate that the U.S. is no longer seeking approval from UN or NATO allies for a strike. But the case for action in Syria is thin—and there are plenty of reasons to avoid becoming mired into another Middle East conflict. Here are eight reasons to avoid war in Syria:

1. If the rebels win, it's bad news for the U.S. Assad is no friend to the U.S. But neither are the rebel groups leading the charge against the Syrian dictator. Indeed, many of the rebel factions have strong ties to Al-Qeada. If the rebels successfully oust Assad, it's entirely possible that they will attempt to set up a new regime that is intensely hostile to the United States. Intervention on the side of the rebels would also complicate America's already-fraught relationship with Russia, which is close with the Assad regime.

2. If Assad wins, it's bad news for the U.S. Especially if the U.S. is seen to have openly sided with the rebels. A win for Assad is a win for anti-American forces Iran, which would see its influence in the region strengthened. It's also a win for Hezbollah, which is closely linked with Iranian extremists. With no good option, then, the U.S. is better off staying out of the conflict entirely.

3. It's far from certain that any "limited" actions would actually be effective. Most of the talk right now revolves around the possibility of limited cruise missile strikes and/or no-fly zone enforcement. But as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey told NPR last month, the possible results of enforcing a no-fly zone could "include the loss of U.S. aircraft, which would require us to insert personnel recovery forces. It may also fail to reduce the violence or shift the momentum because the regime relies overwhelmingly on surface fires -- mortars, artillery, and missiles." The same goes for targeted strikes. Here's how Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies explained it to the L.A. Times: "Can you do damage with cruise missiles? Yes," he said. "Can you stop them from having chemical weapons capability? I would think the answer would be no. Should you limit yourself to just a kind of incremental retaliation? That doesn't serve any strategic purpose. It doesn't protect the Syrian people, it doesn't push Assad out."

4. It's hard to keep limited actions limited. As Chairman Dempsey further cautioned, "Once we take action, we should be prepared for what comes next. Deeper involvement is hard to avoid." And then what?

5. There's no endgame. Not in Syria, where there seems to be no plan beyond a limited initial strike. And not in the region or the world, where the U.S. would be all but committing itself to opposing, through military force, chemical weapons regimes across the world. The problem is that there's no clearly stated long-term objective — perhaps because no obvious long-term objective is achievable. Given that strikes are unlikely to completely eliminate Assad's chemical weapons capabilities or end Assad's capacity to slaughter through more conventional means, it's not clear what they would be for. Which means there would almost certainly be pressure to give them meaning by increasing America's commitment to the conflict.

6. The chemical weapons "red line" was already crossed. Roughly a year ago, President Obama said that the use of chemical weapons by Assad against his own people would constitute a "red line" that would change how the White House views the Syrian conflict. Talk of strikes has increased following reports of a chemical weapons attack in Damascus last week said to have killed hundreds. But American officials already believe that Assad has used chemical weapons on a somewhat smaller scale over the past year. The latest attack appears to be larger than previous chemical strikes, but that's a murky distinction. The red line, in other words, looks more like a gray area.

7. It won't be easy. Reliable GOP hawk John McCain has said that strikes could be carried out "easily" and "would not put a single [American] life at risk." Moreover, he said, a strikes could be carried out in just a couple of days. But the big lesson of so many U.S. military interventions is that they are rarely as easy, quick, or costless as backers promise. As George Friedman of the global intelligence firm Statfor wrote recently, "Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya have driven home the principle that deposing one regime means living with an imperfect successor. In those cases, changing the regime wound up rapidly entangling the United States in civil wars, the outcomes of which have not been worth the price."

8. The public opposes military intervention by a wide margin—even if chemical weapons have been used. The American public has grown tired of war, and doesn't want to get embroiled in yet another complex civil conflict. According to a Reuters poll released over the weekend, some 60 percent of the public opposes military intervention in Syria's civil war, while just 9 percent support it. Support for intervention is still extremely low if it's established that Syria used chemical weapons, with just 25 percent saying they would support action of Assad used chemical weapons on civilians.

Show Comments (115)