As Government Grasps For Taxes, Brace for an Unwinnable War Against You

Uncle Sam has worked up an appetite

Many years ago, I dropped out of law school. As wise a decision as fleeing from law school is at any time, it left me unemployed and debt-ridden in Boston in the midst of the recession of the early 1990s. Cut off from my cozy, if temporary, academic existence, and with my list of creditors rather lengthier than my list of potential employers, I did what any enterprising young man does in difficult economic times: I sold…umm…genetic material to the highest bidder in a city full of competing researchers; I worked as a paid medical guinea pig in a series of increasingly bizarre experiments involving both cocaine and marijuana, and wrote about the experience for Penthouse; and I started a little house-painting and handyman business off the books.

You want hard-wood floors stripped and refinished? I did that. You want firewood split? I did that. You want classic trim painted a different color than the walls? Yep. How about painting over ancient leather wallpaper that just drips character? I…refused that job. Come on, that's a piece of history on your wall. Crusty, cracking history.

I did it all for cash, of course. No checks, no credit cards, and certainly no taxes.

Of course, at my income level at that time, taxes would likely have meant the difference between protein and no protein in my diet in any given week. But I doubt that Uncle Sam would have cared much about my financial straits or my efforts to keep my head above water—he always wants his pound of flesh.

In fact, each tax season, as the U.S. federal government's ongoing spending spree grows ever-more clearly uncontrollable, politicians' proposals inevitably turn to collecting taxes owed under the law, but never paid. Closing the so-called "tax gap" is an easy sell to the public because it sounds like simple fairness.

Fueling politicians' appetite for tax dollars uncollected, "[t]he voluntary compliance rate—the percentage of total tax revenues paid on a timely basis—for tax year 2006 is estimated to be 83.1 percent," according to a thrill-a-minute report released by the Internal Revenue Service in January of 2012. That compliance rate, or rather the corresponding noncompliance rate, resulted in a gross tax gap estimated at $450 billion dollars left beyond the grasp of the nation's gatherers of other people's money. Even after enforcement efforts, $385 billion is believed to have slipped away.

Those hundreds of billions of uncollected dollars have politicians salivating. What less provocative way could there be for funding the government's ever-growing wish list (or, maybe, reducing the debt just a tad) than by going after money that is owed under existing tax laws, but which is being hidden from the IRS? After all, it's about making people pay their fair share, isn't it?

But there's a difference between fever dreams of 100 percent compliance and the real world, and the fact is that no law ever achieves complete compliance. In fact, the IRS is already the envy of tax collectors around the world for the relatively large degree of cooperation it receives from the American people, resulting in a smaller tax gap than other nations could ever hope to achieve. And trying to collect the elusive billions that remain outside official reach would mean an escalating and doomed war by the government against the American people.

What do I mean?

First, you have to understand that the IRS is one of the few tax agencies to release its compliance figures. When you look at the numbers for other countries — painstakingly compiled by independent economists — the reason is clear.

In What Explains Tax Evasion: An Empirical Assessment Based on European Data, a paper prepared for the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, authors Edward Christie and Mario Holzner calculated tax compliance rates for European Union members and several candidate countries. A separate paper by Lars P. Feld and Bruno S. Frey, Tax Evasion in Switzerland: The Roles of Deterrence and Tax Morale, calculated Swiss income tax compliance.

In terms of personal income tax, the most recent compliance rates calculated in the paper are shown below. For the purposes of a more apples-to-apples comparison, I've used numbers only from more-developed Western European countries to compare to the U.S.:

Personal Income Tax Compliance Rates in Europe

Austria: 74.80%

Belgium: 70.15%

France: 75.38%

Germany: 67.72%

Italy: 62.49%

Netherlands: 72.84%

Portugal: 68.09%

Switzerland: 77.70%

United Kingdom: 77.97%

United States: 83.10%

Is anything jumping out at you? How about the fact the U.S. tax compliance, at 83 percent, is higher than other countries have been able to manage?

This actually is no secret, no matter how much certain Americans like to pretend that Europe is a magical place where people eagerly cut checks to the tax man to pay for a grab-bag of social services. Italian President Silvio Berlusconi once described tax evasion as a "natural right," reflecting the views of many of his countrymen. In practical terms, this likely puts Italy on the same footing as Belgium, where dodging taxes is widely described as the country's "national sport."

In a November 2011 column, CNN's Tim Lister pointed out, "When [researchers] analyzed Europe's 'shadow economies' — defined as areas that fall beyond the reach of the taxman — those of Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal were much larger (relatively) than those in northern Europe.

"Shadow economy" is an interesting measure. Where tax-compliance rates are often held as closely guarded secrets by somewhat embarrassed tax officials, and even when pried loose may obscure differences in measurement and tax laws, the size of the shadow economy can be calculated independently by economists and used as a handy apples-to-apples comparison.

Professor Friedrich Schneider of the University of Linz is a recognized expert in tracking unofficial economic activity. He defines the "shadow economy" as:

The shadow economy includes all market-based legal production of goods and services that are deliberately concealed from public authorities for the following reasons:

1. to avoid payment of income, value added or other taxes,

2. to avoid payment of social security contributions,

3. to avoid having to meet certain legal labor market standards, such as minimum wages, maximum working hours, safety standards, etc., and

4. to avoid complying with certain administrative procedures, such as completing statistical questionnaires or other administrative forms.

So, we're not talking about illegal drugs or other illicit activities here — the shadow economy reflects only things that would be legal if all the taxes were paid and permits secured.

In The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know?, Prof. Schneider estimates the sizes of the underground economies of 21 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries as percentages of their official GDPs as of 2007. They're listed below, in ascending order:

- United States: 7.2%

- Switzerland: 8.2%

- Japan: 9.0%

- Austria: 9.4%

- New Zealand: 9.8%

- Netherlands: 10.1%

- United Kingdom: 10.6%

- Australia: 10.7%

- France: 11.8%

- Canada: 12.6%

- Ireland: 12.7%

- Finland: 14.5%

- Germany: 14.6%

- Denmark: 14.8%

- Norway: 15.4%

- Sweden: 15.6%

- Belgium: 18.3%

- Portugal: 19.2%

- Spain: 19.3%

- Italy: 22.3%

- Greece: 25.1%

Sure enough, the United States has the smallest underground economy of the bunch. Fewer Americans than their counterparts in Switzerland, Canada or (especially) Italy and Greece choose to conduct their business out of sight and reach of the tax and regulatory authorities.

The "why" of tax compliance rates certainly depends on a variety of factors, and these likely vary a bit from country to country. Christie and Holzner point to the complexity of tax systems (interestingly, they believe that too much simplicity may reduce compliance), corruption and income inequality as potential influences on tax compliance.

Overall, though, Christie and Holzner conclude that tax rates matter — when rates are higher, people hide more money; when rates come down, people put less effort into evading the authorities. "[W]e found as our most general result that tax evasion is positively correlated with the tax rate itself … reducing average effective tax rates should positively impact on compliance rates."

Schneider agrees, writing in Shadow Economies of 145 Countries all over the World: What do we really know? (PDF), "In almost all studies it has been found out, that the tax and social security contribution burdens are one of the main causes for the existence of the shadow economy." He adds, "The bigger the difference between the total cost of labor in the official economy and the after-tax earnings (from work), the greater is the incentive to avoid this difference and to work in the shadow economy."

That's not that surprising, is it? If you raise the price of anything, fewer people are willing to pay. There's no reason that shouldn't go for government as much as for cars or potato chips.

But governments are the only vendors that don't let customers walk away. And the U.S, government's latest emphasis on squeezing Americans ever-harder for the change in their pockets isn't exactly a new idea.

In France and Germany, ferocious tax police are kicking in doors in an effort to squeeze the last euros from tax evaders great and small. The German authorities have even taken to paying for data stolen from banks in other countries in an effort to find where the money is hidden.

And still the underground economy, beyond the reach of tax authorities, thrives and whets the government's appetite.

Abuses by tax collectors in the United States led to congressional hearings in the 1990s. Tax agents were waging SWAT-style raids on homes and businesses, using phony credentials, pointing guns at people, and generally acting like an occupying army. The IRS pulled in its horns after public outrage led to tongue-lashings by powerful lawmakers and much embarrassment.

But when a government is running up a multi-trillion-dollar debt and has abandoned any pretense of fiscal discipline, that tax gap starts looking like a piggy bank, and there are always tax collectors willing to do some smashing.

The international experience suggests that enforcement efforts don't do much to budge the bottom line. Compliance is largely a matter of finding the right price. Keep taxes within an acceptable range and maintain a system that people perceive as reasonably fair, and you'll get a decent amount of compliance (but never 100 percent). Raise the price, and people stop paying.

And when they stop paying, it's hard to get those customers back. Writes Schneider (PDF):

But even major tax reforms with major tax rate deductions will not lead to a substantial decrease of the shadow economy. Such reforms will only be able to stabilize the size of the shadow economy and avoid a further increase. Social networks and personal relationships, the high profit from irregular activities and associated investments in real and human capital are strong ties which prevent people from transferring to the official economy.

That is, once people get used to operating in the shadows, and make connections there, it becomes increasingly difficult — and unattractive — for them to come back above-ground.

Just recently, to resolve the "fiscal cliff" financial crisis that predated the sequestration financial crisis, politicians hiked income taxes on higher-income Americans, and sneakily raised payroll taxes on most of the rest of us. If the economists are right about the record of taxes and tax enforcement around the world, that will lead to higher levels of non-compliance, no matter what enforcement efforts are put in place.

But it's not only taxes – the rest of the economic environment matters, too. Remember, two of the four reasons Schneider gave for people fleeing the tax man have to do with regulations and bureaucracy. And, indeed, he finds, "every available measure of regulation is significantly correlated with the share of the unofficial economy and the sign of the relationship is unambiguous: more regulation is correlated with a larger shadow economy." In particular, enforced regulations — not just nominal red tape to which people turn a blind eye — drives people into the shadows.

Summarizing the argument, Professor Pietro Reichlen of Rome's Luiss University told the Financial Times in a June 2011 article on Europe's hidden economy, "Among the main causes of the black economy is the level of taxation. The higher the tax and the regulatory burden the bigger the shadow economy of the country." He recommended simplifying and reducing taxes, reducing the regulatory burden, including laws that make it difficult and expensive to hire and fire workers, and improving often-corrupt, archaic and unresponsive judicial systems.

But that's not the tack the current administration has taken. The Associated Press reported in December 2012, "since the election, the Obama administration has quietly reopened the regulations pipeline."

Investors Business Daily cautions:

The cost of regulation to the economy is already $1.8 trillion a year, according to reliable estimates by various think tanks and by the Small Business Administration.

In coming years, that will surge. In the first three years alone, Obama added $46 billion a year to regulatory costs — compared to just $8.1 billion under Bush.

So, taxes are going up, not down, and regulations are tightening, instead of loosening. even as the federal government wants more revenue. And our fearless political leaders do want more. Even with the oh-so-brutal cuts … err … reductions on the rate of increase in federal spending, the federal government is expected to run a deficit of $845 billion this year, according to the Congressional Budget Office (PDF). In fact, it's expected to run deficits in the hundreds of billions of dollars for the foreseeable future. That's based on assumptions of 3.4 percent economic growth in 2014, and 3.6 percent growth from 2015 through 2018. That's after economic growth of 2.2 percent last year and 1.8 percent in 2011 (PDF).

In fact, the CBO's depressing outlook is based on unrealistically optimistic forecasts for economic growth and revenue collection!

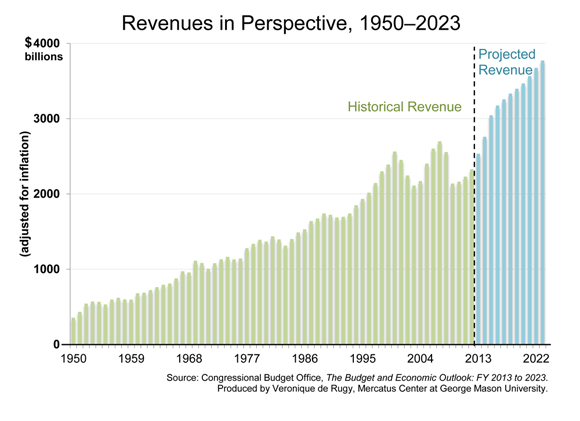

As Reason columnist and Mercatus Center economist Veronique de Rugy points out:

The annual projected revenue growth between 2013 and 2023 is 4.5 percent, which is much higher than the historical average of 3.3 percent. In particular, revenue is projected to grow at an average annual rate of over 9 percent for the next three years. This is nearly three times the historical average. Moreover, as the second chart shows, the CBO projects a positive revenue collection growth for ten consecutive years, an unprecedented trend.

The chance of the United States government collecting the tax revenue its official predictions now call for is about zilch. When government officials don't get what they want, they tend to escalate. That has happened with Prohibition, the war on drugs, efforts to stamp out Internet gambling — and tax enforcement. Tactics get nastier, and nastier, and — as they don't achieve the desired result — turn increasingly abusive.

And kicking in doors and staging intrusive audits runs the risk of making the government "the enemy" in the eyes of many Americans. That means a big hit on the "tax morale" that helps determine taxpayers' willingness to cooperate with the authorities. Nobody willingly surrenders their lunch money to somebody they hate. So the tax gap will grow even as enforcement efforts become more intrusive.

So, as politicians and talking heads chatter on about closing the tax gap, keep in mind that they're talking about waging an unwinnable but still nasty war — against you.

Show Comments (39)