The Difficult Policy Choices of ObamaCare's Medicaid Expansion

Florida Governor Rick Scott's decision to participate in ObamaCare's Medicaid expansion reveals the tough politics of that choice: Scott is not only a Republican but a vocal critic of the health law who spent millions of his own money opposing its passage and vowed that his state never participate in any part of it. Yet last month, after facing pressure from hospital groups and others, he decided to go ahead with an expansion of Medicaid under the law anyway. But now he's getting pushback on that decision: committees in both houses of the Florida legislature have either delayed or rejected his Medicaid proposal.

But it's more than tough politics. It's also tough policy. A new paper from Charles Blahous, one of Medicare and Medicaid's public trustees and a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center, sheds light on some of the difficult choices that states face in deciding whether or not to expand Medicaid.

Backers of the law have argued that the decision to expand Medicaid should be a no-brainer: The federal government, after all, is paying for 100 percent of the expansion through 2016, and then declining 90 percent by 2020. It's free money, the argument goes. Why would states turn it down?

For one thing, expanding Medicaid isn't cost free to states—even during the initial years when the federal government is paying for 100 percent of the cost of the coverage expansion. One reason is what's known as the "woodwork effect": Yes, the federal government will initially pay 100 percent of the cost of covering the newly eligible. But there are millions of Americans who were already eligible for Medicaid programs before ObamaCare passed—and yet weren't enrolled. Thanks to the mandate and the enrollment push, many of those people will become covered following the expansion. And states will have to cover the tab for all of the previously eligible.

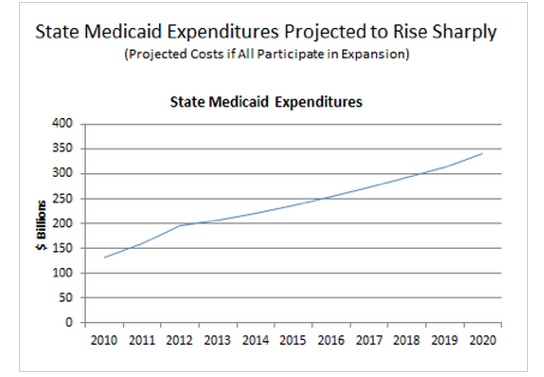

More broadly, even if the cost of participating in the expansion is low, it has to be considered in the context of the substantial increase in Medicaid spending that's projected over the next few years—and the already high share of state budgets the program accounts for. As Blahous points out, the cost of Medicaid is equal to an average of about 24 percent of state budgets, and the bipartisan State Budget Crisis Task Force has warned that it is already "crowding out other needs."

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, meanwhile, currently expects the state portion of the cost of Medicaid to grow by 158 percent over the next decade, should all states opt in to the expansion.

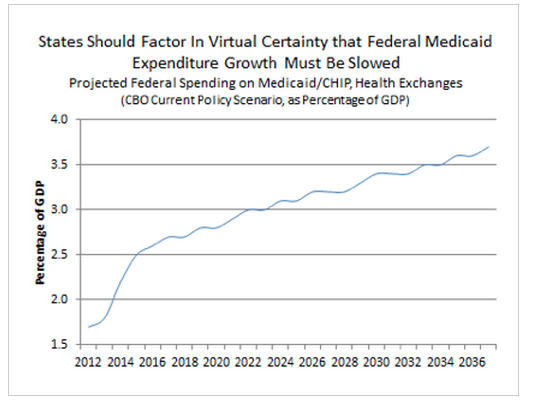

The federal government will be spending a lot more too. Here's what that looks like:

The cost of the expansion also has to be considered in the context of the overall federal financial trajectory, which, needless to say, isn't good. "Given the current state of federal finances," Blahous argues, "it is unrealistic to assume that the federal government will make all future Medicaid payments now scheduled under law." Shifting more costs to the states in the future, he says, is "virtually assured."

You can already see this on the horizon. The Obama administration has implicitly admitted that the program's costs are going to have to be reduced somehow: For the last few years, it's been fighting a legal battle to ensure that states have an absolute right to cut the program's reimbursement rates as low as they wish. The Obama administration's position is that "there is no general mandate under Medicaid to reimburse providers for all or substantially all of their costs." This is in the health program that notoriously pays the lowest reimbursement rates in the nation.

For states, it's the medium to long-term fiscal picture that presents the biggest worry. The long-term politics of federal budgeting make short-term state policy choices rather dicey: Who knows what Congress will do as the cost of government health programs rise and the already bad budget situation grows worse? Cost shifting to states may not be inevitable, but it's quite likely, which means that even if expanding Medicaid is essentially free now, it almost certainly won't be in the future.

Show Comments (6)