The Freedom Factor

What foments violence and war? What fosters peace? A political scientist tallies the evidence.

Democratic leaders should recall that wars between democratic states have not been seen in the twentieth century. Indeed, wearied and demoralised though modern man's democracies have sometimes been, there is no instance at all of any of them being bellicose against each other: an elementary truth which their leaders should take a little trouble to point out to their critics.

—Hugh Thomas, A History of the World, 1979

Of the four horsemen of the apocalypse—war, strife, famine, and pestilence—mankind has all but eliminated one and is succeeding in reducing a second. The plagues and diseases that were a scourge of death through whole nations and continents have been conquered by medical science, modern sanitation and health services, and international cooperation. Disease is still with us, of course, and epidemics do occur. But these are now isolated and contained; at their worst, they are nothing resembling those of the past.

And although mass hunger and starvation is still a huge and heart-rending problem, particularly in Africa, agricultural and nutritional research and advances in agricultural machinery and techniques have made it possible to conquer hunger. Mankind now knows and has the wherewithal to do what should be done; famine is largely a problem of economic and political organization, of values and of dislocations due to war and strife, not of knowledge or technology.

But while pestilence is vanquished and famine reduced and controllable, war and violent strife are still the supreme mass killers. We are presently no less consumed by collective bloodshed than when Thucydides wrote The Peloponnesian War over 2,400 years ago. Consider: World War I killed about 10 million people; World War II about 40 million. Add the other several hundred international and civil wars, plus the mass killing of their own citizens by the Hitlers, Stalins, Idi Amins, and Pol Pots, and the death toll from war and violence in the 20th century probably well exceeds 200 million. And this is without a nuclear exchange.

Before such figures, most people feel helpless. Among the diverse plans and proposals for defeating, or at least reducing, this great scourge of mankind, not many have been realistic. Of the practical ones, none has been successful. As I write this, people are dying en masse in civil or international wars involving El Salvador; Angola; the Republic of South Africa in Namibia; Morocco in the western Sahara; Chad; Israel, Syria, and the Palestinians in Lebanon; Iran and Iraq; the USSR in Afghanistan; and Vietnam in Cambodia.

No wonder many are skeptical of mankind's ability ever to control such violence. Nothing has helped—not the growth in international organizations, education, cross-national ties, popular antiwar movements, or science. The result is deep frustration and despair, partly reflected in the latest mass movement opposing nuclear weapons: if war is to occur, and history and current events seem to say that it will, then at least deprive states of those weapons that may destroy us all in the final apocalypse.

There is hope, though, and it comes from scientific research in recent years on collective violence. Pestilence was conquered in theory when science answered the what, how, and why; it was conquered in fact through appropriate organization and medical services. Famine likewise has been beaten in theory by science and technology, while the political and economic organization most conducive to prosperity has subsequently ended famine in many parts of the world. For war and violence, we are still at the state of conducting scientific research to subdue them in theory. But that research has already produced some highly significant and practical results. In a nutshell, what social science has found is that the more freedom a state has, the less its internal and foreign violence.

While there were isolated early attempts to apply scientific methods to understanding and controlling war and violence (notably by Lewis Fry Richardson, an English meteorologist and Quaker, and by Quincy Wright, a professor of international law and relations at the University of Chicago), the scientific study of war and violence really began in the mid-1950s. The great fear of nuclear war, coupled with an appreciation of the success of scientific research during the Second World War, stimulated many with scientific skills and dispositions to apply them to this area. By the early 1960s, there had emerged within political science a new discipline focused on understanding and resolving violence. Today, peace science, or irenology (from Irene, the Greek goddess of peace), is a fully functioning discipline with journals, scientific associations and meetings, a community of scientists, and the first newly established academic departments granting advanced degrees.

A pacifist in my youth, deeply affected by the killing of World War II and horrified by the potential of nuclear weapons, I have been part of the growth of irenology from its beginnings. I began my academic work in physics and mathematics, transferred to political science, and began in the late 1950s to apply the tools of science to understanding war and peace. Here, I will keynote the major conclusion of over 15 years of research, a conclusion that I believe offers great hope for minimizing violence and eliminating war.

I would not be a good scientist if I did not concede that such hope must be qualified. Enough research has been done by enough different scientists on enough different cases and periods of time and using enough different methods to say that the results are significant and most likely valid. But much more remains to be done, and future research could modify or negate these results. When facing the most serious of mankind's problems, however, such necessary caution can be overdone (especially when numerous politicians and intellectuals, without having seriously studied the problem, proclaim one cause or solution to war to which they would commit mankind's resources).

In what follows, I will present some of the evidence for and explain two related conclusions about violence and war: that freedom is inversely related to violence and that there is no war between liberal democratic states. A liberal democracy is defined as a state that respects basic civil liberties and political rights (such as freedom of the press, religious freedom, and open, competitive elections with a near-universal franchise). A "free state" is not defined relative to other states, as would be the case if the internally freest one-fourth or one-fifth of all states were taken as the sample of those with freedom. Still, the threshold for a liberal democracy used here may be too low; that is, a fair amount of government control and dictation is not precluded. An interesting result, however, is that when freedom is considered relatively, as when it is correlated with violence, we find that the more freedom, the less violence; the implication is that even in liberal democracies, what violence there is could be reduced further by increasing individual freedom.

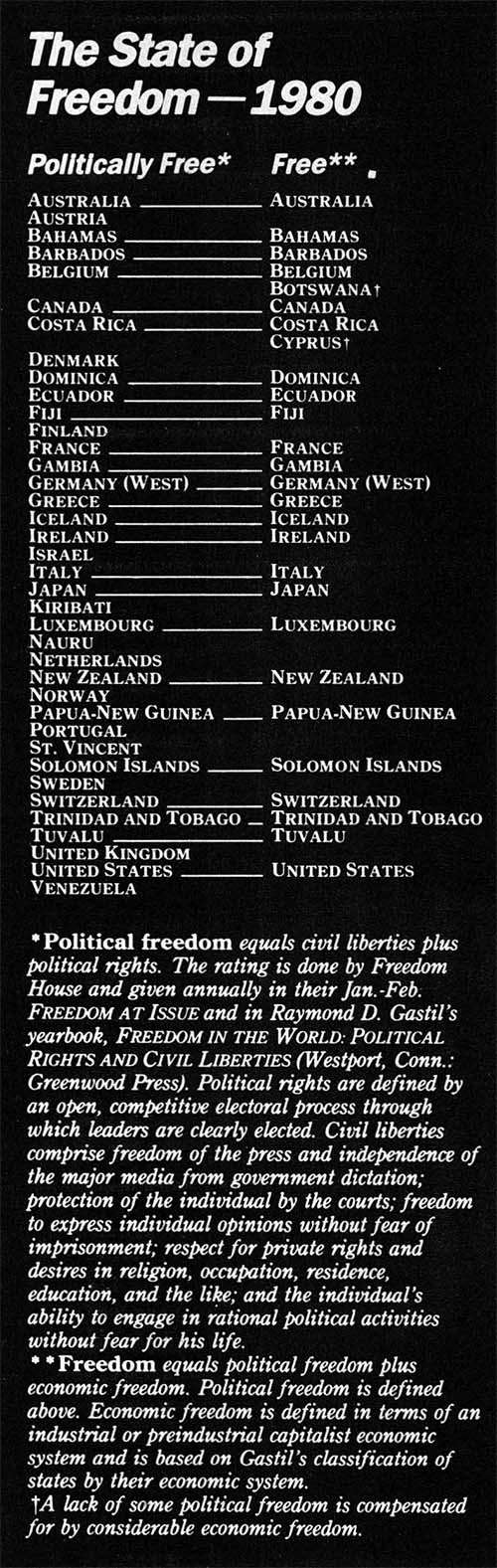

Now, some evidence. In the historical period for which there are systematic data, 1816–1981, there were more than 50 interstate wars, not one of which actively involved an established liberal democracy on both sides. This lack of wars between democracies is sufficient to show the great peace-making and peace-keeping virtue of freedom. It cannot be statistically explained by lack of common borders or by the existence of few democracies. (Freedom House identified some 38 liberal democratic states in 1980; see the list on page 35.) Only some common internal factor—the existence of freedom—can explain the result.

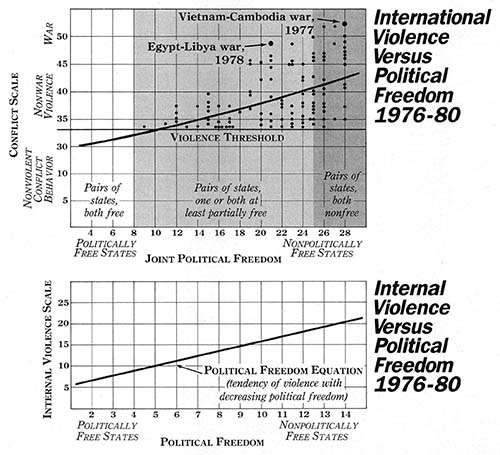

Additionally, democracies not only avoid wars among themselves but have minimal violent interactions with other nondemocratic states as well. To explore this point in detail, I identified every known case of violence between two states during the five-year period 1976–80. I assigned a (rank-order) numerical score to each case, based on the degree of violence involved. (Nonviolent conflicts were scored from 1 to 33, violent conflicts short of war received scores of 34 to 43, and wars were scored from 44 to 52, depending on their seriousness.)

In order to assess the relationship between violence and political freedom, I then derived a combined score for political freedom in the states involved in these conflicts. I used here the Freedom House seven-point rating scales for political rights and civil liberties, where 1 represents the greatest extent of freedom and 7 the least. By adding together the ratings on these two measures and then the resulting political-freedom ratings of the two countries involved in a conflict, I obtained a measure of the degree of joint political freedom. The higher this number, the less joint political freedom for the pair.

The top figure on page 34 shows what happens when we plot the cases of interstate violence on a graph, indicating the degree of violence on the vertical axis and the joint political freedom on the horizontal axis. For example, the Egypt-Libya War in 1977 and the Vietnam-Cambodia War in 1978 are both high on the conflict scale, but the latter is much further to the right because the two states have a high degree of nonfreedom. In fact, the horizontal axis can be divided into three regions: pairs of states that are both politically free, pairs of states in which one or both is partially free, and pairs of states (like Vietnam and Cambodia) that are both nonfree. It is notable that there is not a single incident of violence between the pairs of states rated politically free.

Some basic statistics can be used to define a mathematical function describing the pattern made up by all these data points. The result is the slightly upward-curving line drawn in the figure—what statisticians call a "growth curve." This curve crosses the violence threshold (the point where the vertical scale changes from nonviolent to violent conflicts) outside the region of pairs of politically free states. In other words, there is solid statistical evidence, at least for the years 1976–80, that free states do not engage in violent interactions and that violence between states increases with their lack of freedom.

Moreover, democracies do not even approach the threshold of violence. Military warnings, alerts, threatening troop movements, or shows of force between democracies are virtually unknown. In the course of my research on this five-year period, I have also plotted the peak conflict behavior (the highest level of conflict, whether violent or not) between pairs of states. When I statistically derived a curve that fits these data points, I found that it moves up sharply as we progress along the horizontal axis from politically free to nonfree pairs of states. Peak conflict between free states consisted of negative communications and negative sanctions and only in a few cases of warnings and defensive acts. The violence threshold is not crossed over until we move well into the region of partially free state pairs.

What about collective social or political violence within states? Here also, freedom reduces or eliminates collective violence. This is illustrated by the bottom figure on page 34, which shows the best-fitting curve for data points for 261 cases (all I could find) of collective violence within states for 1976–80 (riots, revolts, rebellions, assassinations, guerrilla war, terrorism, social violence, etc.). Again, although the data points themselves are not shown, each incident's degree of violence was plotted against the political freedom score of the state in which the violence occurred. The result is quite clear: the less freedom within states, the more collective violence.

The political freedom scores used here have been based on Freedom House's measure of the extent to which civil liberties and political rights are respected within these states. This measure, however, ignores the extent of economic freedom within a society. (For example, the adjacent table shows which of the 38 states rated politically free in 1980 also have substantially free economies.) In my own research, I have also considered total freedom (that is, political plus economic freedom) in the statistical calculations used to derive the relationship between freedom and violence. The results were similar curves, displaced somewhat from the ones based on political freedom alone. What I found was that for a given level of political freedom, the level of interstate violence is greater without economic freedom. I obtained the same conclusion for internal violence. In short, economic freedom is a (statistically) significant factor in reducing both internal and interstate violence.

To sum up, freedom minimizes violence. Within free states, there is the least violence. And between free states, war does not occur and violent conflict is virtually unknown.

Is the demonstrated inverse relationship between freedom and violence explainable? Two concepts play a critical role in understanding this interesting result. One is cross-pressures, the other polarization. Spontaneous societies in which the government's role is small have a variety of different contending powers (such as the churches, corporations, large landowners, labor unions, the press), diverse competitive interests, and variegated groups. Society is pluralistic and dynamic; social forces point in different directions. As a result, interests are cross-pressured and segmented; people are pushed and pulled in different directions by varying obligations, benefits, and opportunities. The satisfaction of any one interest usually requires compromising or yielding others. Moreover, the same people may be top dogs in one group, underdogs in another.

With diverse multiple interests and participation in multiple groups in different ways, the individual in a free society is a broker among his contending interests, having to decide which to satisfy and which to ignore. It is then difficult to be overly excited about any one interest, for then one may lose out on some others. In other words, "win some, lose some." This perspective is the hallmark of an exchange society and its limited government. And it is this perspective generated by cross-pressures and pluralism in a spontaneous society that tends to minimize social violence.

Nonetheless, for some, vital interests may still be at stake; violence may occur. But with overlapping groups, differing class memberships, and cross-pressured interests, no conflict front can form across the larger society. What frustration and associated violence do occur are either localized and contained or are diverted into numerous channels and drained off before many people, groups, or interests are involved.

As for the foreign relations of such states, external violence is checked by the existence of multiple, often conflicting, elites whose interests are divergent and segmented, checked and balanced. Moreover, political elites are dependent upon the support of a public usually unwilling to bear the cost in taxes, property, and blood of foreign adventures and intervention, unless aroused by an emotionally unifying issue. Even then, the public cannot be trusted to pay the price of foreign violence for long and may turn on those responsible even in the midst of war (witness the Vietnam war for the United States).

Of course, an emotional and patriotically aroused people can itself be a force for war (as in the US war on Spain in 1898). But this is to underline that the essential diversity of interests and values of free citizens must be overcome—a sufficiently unifying national stake or value must be at issue—before elites are unrestrained by a free press and contending centers of power and are unaccountable through free elections. For these reasons, the freer the people of a state, the less likely are its elites to commit violence against other states. This is not to deny that such violence does occur (as in World War II, and recently the Falkland Islands). It is to say that free states are least prone to international violence and war.

Most important, this inhibition becomes a mutual barrier to violence between liberal democratic states. Their mutual domestic diversity and pluralism, their free and competitive press, their people-to-people and elite-to-elite bonds and linkages, and their mutual identification and sympathy foreclose on war between them; violence may occur only upon the most extraordinary and unusual circumstances.

Turning now to the second concept, polarization, consider a society in which government uses coercion and force to direct most social and economic activities, without countervailing civil liberties or political rights. Much of what one does is therefore controlled by the same "they." One supreme elite commands all others, regardless of the organization or group involved—whether churches, farms, factories, or schools; provinces, cities, or towns; families or individuals.

The critical effect of this is to polarize classes, groups, and interests. A single, central status quo determines one's overall rights and benefits: what to own, eat, earn, read, and worship; where to live and work. This splits society, creating a latent conflict front cutting across groups and organizations and polarizing all into a society-wide, two-class division: those who command and those who obey. Without numerous cross-pressured interests, there are no longer compromise and balance among them. This polarization of society means that the most important interests—even life—are vitally affected by which side of the class front one is on.

For this reason, any development of leadership in the obey class is a most serious threat to the governing elite and is harshly dealt with. And obey-class political sensitivity and consciousness that might dangerously challenge the legitimacy of the elite are prevented through mind control and propaganda, selective isolation or elimination of dissidents, or jingoistic, nationalist campaigns calling for political unity and support against a foreign evil.

Even aside from this actual violence of the government against the people (which alone makes coercive societies the most violent) or against itself through purges and coups, there is the ever-present potential for class war. The sharp class division across society between ins and outs resembles a geological fault line across the earth. Pressure builds up on both sides, until the stress is such that a slip in one place may unlock the whole length, producing a severe earthquake over a large area. Similarly, when violence occurs in a polarized society over one issue and in one place, it can trigger violence along the entire class front. Thus, the social earthquake: mass violence, revolution, and class war.

This polarization affects a state's foreign relations, as well. The ruled have little power to restrain or resist the foreign adventures of their rulers, who, in any case, are responsible only to themselves. Moreover, these rulers' control over society and the media enable them to treat their people as one large army, whose mass hostility and resources can be created, mobilized, and directed at any foreign power.

Between states with such totalitarian governments, power goals and calculations are the determinants of policy. Economic exchanges, social bonds, similarity in culture, historical alliances, and transnational people-to-people linkages are all minor notes in totalitarian foreign policies. No wonder that when totalitarian states meet, violence and war are more likely than for any other combination of political systems.

Of course, there is a gradient here; many different varieties and shades of democratic and totalitarian states exist. And in between are different authoritarian states, ruled less by coercion than by custom, authority, and legitimacy. Regardless of this variety, however, as the civil liberties, political rights, and economic freedom decrease in a state, its internal cross-pressures should likewise decrease as interests become polarized. The state's internal and external violence should then increase. And this is what systematic analyses of data on violence confirm.

Why has this critical relationship between violence and freedom been missed or forgotten by all but a few contemporary advocates of the free society? First, I suggest that the frequent involvement of liberal democracies in war—such as World Wars I and II, Korea, Suez, and Vietnam, not to mention a multitude of war crises—has eroded the classical liberal conviction that freedom and free trade further international peace and harmony. What has not been seen, since this is more a matter of scientific analysis, is that while such states have had violence and war, they have had significantly less, and that indeed, the more unfree a state internally, the greater its violence and war.

Second, I believe that people generally look at states one-for-one. The relationship between democracy and war is generally perceived as a question of whether such states have wars or not. However, much of what is important in the relationship between freedom and violence is in fact a matter of what states are paired. It is not that liberal democratic states do not have wars. They do. It is that they have no wars and hardly any violence between them.

And third, it is clear to me that much of the professional literature on violence, war, and peace is produced by contemporary liberals and socialists who, I would say, are ideologically blinded to what the evidence shows. They usually prefer to see violence and war as endemic to international "anarchy," international and domestic "inequality," capitalist "exploitation," multinational corporations, and the lack of a welfare-liberal or socialist world government. Rigorous research rather strongly indicates, however, that they have turned things around: the combination of political liberty and capitalism is most peaceful, not least; the combination of political liberty and a socialist economy is less peaceful, not most; and the combination of political repression and a planned economy is least peaceful of all.

Given, as I believe can also be shown, that a free society best promotes the welfare and happiness of its members and best promotes social justice, there is now an additional powerful argument for freedom: peace. For to spread freedom from one state to another is to extend an oasis of nonviolence between states. As far as our science of peace has come, then, the path to minimizing global violence and creating a world free from war appears to be an extension of civil liberties, political rights, and economic freedom. There does seem to be reason to hope that the remaining two horsemen of the apocalypse—war and violent strife—can be defeated after all.

R.J. Rummel is a professor of political science at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the author of Understanding Conflict and War (5 vols., Sage Publications).

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Freedom Factor."

Show Comments (0)