Balancing Act

Is a constitutional amendment the way to limit runaway taxing and spending?

When Richard Nixon declared in 1973 that, to cope with a growing budget deficit, he would impound funds appropriated by Congress, the screams and howls from the elected representatives of the people could be heard throughout the land. Indeed, it almost seemed like a replay of history: Congress, not the executive, shall hold the power of the purse.

Where have we heard this cry before? Echoes of King John submitting to the barons at Runnymede, the overthrow of Charles I by Cromwell, and the Boston Tea Party sound familiar. Yet, for what may have been the first time, the "power of the purse" was invoked to force the executive to spend funds that had not been collected by a duly voted tax bill.

To those historians who may have noted the irony—and they were surely few—it signaled a major turning point in the history of the American Republic and perhaps for democratic government itself. The battle cry has changed from "No Taxation Without Representation" to "Save Our Subsidies"! The legislative power has passed from tax payers to tax receivers.

Why is the current debate over a constitutional amendment to require a balanced budget so heated? The reason is that the economic life of every American will be touched by the outcome, with some gaining and others losing. The principles at stake may not be as clear as with issues like slavery, women's suffrage, or even the War Powers Act, but the fundamental framework of fiscal policy—and, according to some analysts, even monetary policy—is at issue.

The proposed amendment itself seems innocent enough. Senate Joint Resolution 5, and its companion bill in the House of Representatives, provide that Congress must approve any deficit spending by a margin of 60 percent. Moreover, members must vote on the record—not by one of those famous unrecorded voice votes that are always used for congressional pay raises and banking-law changes. The second section of the proposal requires that tax increases receive a majority vote of the full membership of each house of Congress, not just a majority of the ones who show up to vote.

Given the heat this idea of a constitutional amendment has generated, we have to ask, Is that all? Where is the iron-clad language that would force major cuts in spending? Where is the "irrational" economic theory that we are told should not be enshrined in our fundamental law? Where are the teeth that will eat widows and orphans alive? Indeed, from the perspective of one who knows the benefits of cutting spending, the proposal seems quite mild.

AIR CONDITIONING! GUNS! BUTTER!

Once upon a time, Congress would vote to raise or lower import duties and would appropriate money for the army, navy, post offices, and public works like roads, canals, and harbors. And that was about it. Because Washington is such a miserable, hot place in the summer, Congress would meet in the winter and get out of town quickly.

The income tax, FDR's New Deal, the Second World War, and the invention of air conditioning changed all that. Our government has become a year-round passion, and the renovation of the old city is based on a growing demand for office space by corporations and law firms to set up lobbying offices. Democracy has come to mean that every social class and interest group has an agency or lobby in Washington to get its "fair share" of the public pie. Transfer payments to individuals and local governments, the amounts determined by automatic formula, now constitute over half of the federal budget. Interest on the national debt takes another 13 percent.

Veterans benefits, Social Security, and agricultural price supports were the first great "entitlement" programs. Criteria were established by Congress for people who would be entitled to benefits, as a matter of right. Thus a new theory of human rights was popularized—"to each according to need." In Washington, this is called equity (in contrast to the classical formula for equity: Thou shalt not steal). Most of the current $800-billion-a-year federal government spending is passive—those entitled simply come to the public granary and take their share. And this $800 billion doesn't even include loan guarantees, the unfunded liability of pensions, and the contingent liabilities of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, the International Monetary Fund, etc., etc., etc.

Frédéric Bastiat wrote his classic, The Law, over a hundred years ago, but his central point well describes our dilemma today: the state is that great fiction by which everyone attempts to live at the expense of everyone else. Any particular program, whether large or small, tends to benefit an identifiable group of people—and it is easier to organize a special-interest group to lobby Congress than it is to organize a general-interest group to seek repeal of subsidies and privileges.

A brief examination of the political role of milk producers or maritime unions is instructive. These industries maintain a very high level of political campaign contributions. Not surprisingly, they also receive significant subsidies from the Treasury as well as restrictions on competition that further enhance their wealth. Yet, every other taxpayer and consumer in the United States loses only a few dollars per year to these legalized brigands. What may be a minor annoyance, or even an invisible cost, to millions of people is a large pot of gold to those working night and day in Washington to defend their positions.

The most vivid image of this problem is the analogy offered by James Dale Davidson, of the National Taxpayers Union. Assume you selected 435 people off the street and gave them each an American Express credit card with a single, common account number. Assume each of them would be responsible for 1/435th of the monthly bill, but anything the individual could buy would be his or hers to keep. Obviously, the system of incentives is skewed at the margin in favor of greater and greater levels of communal spending.

The central logic of an amendment to the Constitution to require a balanced budget and limitations on taxes is to apply a tourniquet to stop the bleeding. At the present time there is no single point in the budget process at which members of Congress must account for the big picture. There is no need at present to rank priorities in the budget among, for example, an item of defense spending, a new educational program, or a subsidy for the arts. Congress simply treats all programs as equally attractive and funds them year after year. Contrast this to a household or business budget, which by its very nature ranks items by priority and identifies the marginal ones that must be deferred or eliminated.

For the past five years, Congress has not actually adopted a budget for the United States. The agencies in Washington, the military, and the entitlement programs simply carry on with "continuing resolutions." There is no pretense of management or long-term planning nor careful allocation of scarce resources. Indeed, money for the federal government is not a "scarce resource." US Treasury bonds and T-bills are just about the most popular investments in today's risky international capital market. Even if things become really tight for the Treasury, there is a well-known, secretive agency (the Federal Reserve, of course) to supply the necessary funds via "monetary policy."

Europeans do not understand the American fiscal process. In a parliamentary system such as Britain's, the government's announced budget includes a formula for retroactive taxes on individual and business incomes from the previous year, and it proposes a spending plan that is not typically open to amendments. Party discipline is invoked, and either the budget is adopted or the government falls and new elections are called. Government budgeting in the United States, however, has always been a piecemeal process: before 1921 there was not even such a thing as a fiscal year. But then, deficit spending was also unusual.

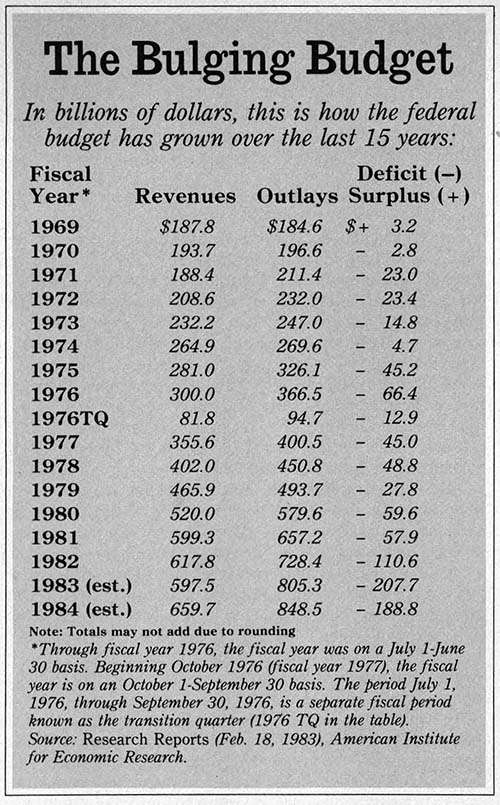

No one argues against the idea of some fiscal discipline—at least not in public, and not explicitly. The controversy is over the method by which to impose it. Should it be a constitutional amendment—or a law adopted by Congress? It must be noted, however, that the more Congress tries to deal with the problem by statute, the worse the problem gets. The Budget Impoundment and Control Act of 1974 (the response of Congress to President Nixon's challenge in 1973) has completely failed. The national debt has tripled, and the budget has gotten deeper and deeper in the red each year.

THREATENING THE KEYNESIAN EDIFICE

One of the primary arguments against the proposed balanced-budget and tax-limitation amendment is the claim that we should not enshrine "an economic theory" in the basic law of the land. Of course, in several places the US Constitution already codifies economic precepts: the regulation of interstate commerce is "enshrined" in Article I, Section 8, as is the power of Congress to borrow money. The anti-slavery 13th Amendment is nothing if not an economic law. And what about the power of Congress to coin money and regulate its value?

The best argument against writing economic theory into the Constitution is the 16th Amendment. The income-tax amendment gave Congress the power to tax "income" but did not define the term. Economists and laymen alike thought it would be obvious. Yet, lawyers and accountants over the years, aided by Congress, have produced millions of pages of analysis, and the term is still not well defined. This perpetual public-works project is known as the regulations and interpretations of the income-tax code, which sustains the CPA industry.

This is important to note, because the central detail of the tax-limitation part of the budget-balancing amendment, section 2, is something called "national income." Now, national income is an artificial number calculated by the Department of Commerce each year. Among its problems, it excludes all wealth and productive services created in the underground economy and counts, or double counts, all the waste and inefficiency of government itself.

The real issue about economic theory and the Constitution, however, is much more subtle. Public policy today is already dominated by an economic theory—an orthodoxy that is threatened by the proposed balanced-budget amendment. What might seem like mild language in Senate Joint Resolution 5 is as threatening to the Washington oligarchy as a denial of the divinity of Christ would be to the Vatican.

John Maynard Keynes once wrote that every practical man of affairs, who may believe himself completely immune from doctrinaire tendencies, is in truth an intellectual slave to some academic scribbler of the previous generation—an economist. A brilliant exposé of the modern orthodoxy is contained in James M. Buchanan and Richard E. Wagner's book, Democracy in Deficit:

In the year [1776] of the American Declaration of Independence, Adam Smith observed that "What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarcely be folly in that of a great kingdom." Until the advent of the "Keynesian revolution" in the middle years of this century, the fiscal conduct of the American Republic was informed by this Smithian principle of fiscal responsibility.…The message of Keynesianism might be summarized as follows: What is folly in the conduct of a private family may be prudence in the conduct of the affairs of a great nation.

The modern view is that government must at all times "hang loose" to stimulate, regulate, or plan the "free-market" economy in the public interest.

Alice Rivlin, head of the Congressional Budget Office, testified before the House Judiciary Committee the day after the Senate voted 69 to 31 last year in favor of the balanced-budget amendment. Speaking, of course, as an objective and impartial scientist, she said the proposed amendment could be "disastrous" because the economy is dependent on government spending—that is, deficit spending.

"The amount of reduced outlays or increased taxes called for by the amendment could endanger the economic recovery and create widespread dislocations if the amendment is implemented at an early date" was her statement to the House committee, cited in the Washington Post the following day. The newspaper, known for its opposition to the amendment, went on to say: "Rivlin's testimony before the subcommittee [offered] the first detailed estimate of what Congress would have to do if an amendment were passed and ratified by the necessary 38 states before October, 1983, and its terms put into effect in time for the 1985 fiscal year." She forecast the 1985 deficit at $178 billion.

The key to understanding the debate over the proposed constitutional amendment is not the economic theory of classical fiscal policy. Nor is it the Keynesian idea of deficits and surpluses as automatic stabilizers. The underlying issue is the role of government in managing the economy. If you believe the government "must" play a role in stimulating, stabilizing, or reindustrializing the nation's competitive market system, the proposed balanced-budget constitutional amendment is about as welcome as an atheist at an Easter worship service.

On the other hand, if you believe the government's central economic planners are incompetent—infected with what Nobel laureate F.A. Hayek has called "the pretense of knowledge"—the amendment is just a procedure for moving the debate from behind closed doors and putting it on the floor of Congress. The amendment, after all, does not actually limit federal spending nor require a balanced budget. All it does is establish a presumption in favor of that norm and require the honorable representatives of the people to go on record whenever they believe they must increase taxes or the public debt. Yet, this scares the pants off some people!

TAKING THE CONVENTION ROUTE

Most of the discussion of the balanced-budget amendment treats it like a sudden slamming of the brakes on a great locomotive, the federal budget, throwing all the passengers on the social railroad into the aisles. The mere fact that such an amendment could be ratified by 38 states, however, ought to suggest that perhaps a transformation would overtake Congress, too.

Between now and 1985 or 1990, a new generation of representatives might take over. This prospect is what frightens Tip O'Neill and the Democratic Party leadership—particularly the idea that just having the proposed amendment out on the table, moving from one state legislature to the next, would precipitate such an electoral transformation.

Public opinion polls in the past three years have consistently demonstrated a strong public attitude in favor of an amendment to the Constitution requiring balanced budgets. Gallup, Harris, Roper, NYT/CBS, AP/NBC—all the polls—have found support ranging from 63 to 75 percent and opposition ranging from 13 to 29 percent. This level of support significantly exceeds that cited in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment, which Congress first sent to the states for ratification in 1972 and bent over backwards to support again in 1979.

Since 1975, 31 state legislatures have adopted resolutions calling upon Congress to submit a balanced-budget amendment for state ratification or to call a limited constitutional convention to draft such an amendment. The action of the Alaska legislature in 1982 is credited with stimulating Congress to vote on the issue, which received the necessary two-thirds majority in the Senate but failed to do so in the House (although it did receive a majority, 236-187).

James Dale Davidson of the National Taxpayers Union is a strong advocate of the constitutional convention route. He points out that we might expect a convention, summoned because Congress itself had failed to act, to draft a balanced-budget amendment with more teeth in it than the one Congress itself has proposed. Moreover, unless Congress becomes worried about this possibility, it will have no incentive to act. The procedures in the House of Representatives in particular to prevent the measure from coming up for a vote are formidable.

Article V of the Constitution stipulates that Congress shall call a constitutional convention when two-thirds of the states request one. At this point, three additional state legislatures would have to adopt a resolution. Nine legislatures have in recent years passed such a resolution in one house but not both: California, Hawaii, Kentucky, Missouri, Montana, Ohio, Rhode Island, Washington, and West Virginia. In addition, four states have adopted resolutions calling upon Congress to submit a balanced-budget amendment for state ratification. It is not a remote prospect that the necessary number of states will call for a convention this year, particularly since the vote in the House that killed the measure in the 97th Congress was so narrow.

The idea of a new constitutional convention is controversial in its own right, because it seems like such a drastic move. The last time a constitutional convention met was in 1787, to replace the Articles of Confederation with our present Constitution. Opponents have charged that a new convention might, for example, repeal the Bill of Rights or come up with some other wild ideas. The reasonable answer to this worry is, So what? Nothing proposed by such a convention could actually amend the constitution without formal ratification by 38 states.

It has been suggested that, to allay fears about a "runaway convention," Congress limit it to considering only a balanced-budget amendment. In response to questions about the legality of such a limitation, the American Bar Association appointed a study group, which concluded: "Congress has the power to establish procedures limiting a convention to the subject matter which is stated in the applications received from the state legislatures."

Former Senator Sam Ervin, who was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee during Watergate, has blasted the opponents of a constitutional convention. "The fear of a runaway convention," he declared, "is just a nonexistent Constitutional ghost conjured up by people who are opposed to balancing the budget."

TAX AND TAX, SPEND AND SPEND

Political columnist George Will is fond of annoying his conservative followers some of the time, so last year he came up with the slogan, "America is radically undertaxed." Congress is clearly unable to cut spending, he reasoned, so the budget deficit must be the result of taxes that are too low. Will's analysis is important to the whole issue of a balanced-budget and tax-limitation amendment, because it tells us the proposal can cut two ways. Politicians don't like to increase taxes, but they do it from time to time.

Would the proposed amendment make it easier to increase taxes? Supporters of the amendment have argued that it would make it easier for Congress to say no to petitions for increased spending, but this is a relative cost. It might become part of the constitutional imperative for Congress to move boldly along the path of least resistance, instead of drifting there as it does today. Sen. Robert Dole (R–Kan.) had little trouble getting Congress to enact the massive 1982 tax increase, because the deficit seemed too large. Would the proposed amendment make this kind of annual tax increase habitual?

The mechanism of the balanced-budget and tax-limitation amendment is the "super majority" required to adopt either deficit budgets or tax increases. In fact, however, the amendment requires only 60 percent approval for a deficit and 51 percent for a tax increase. To be sure, it would also force the spend-more, tax-more members of Congress to stand up and be counted, but Senator Dole had no trouble counting them in August 1982. Even President Reagan was stampeded by the "deficit" bogeyman into reversing his 1980 campaign promise of tax decreases.

It is very fashionable these days to say that a large budget deficit is the cause of all sorts of economic problems, but a careful examination of recent history doesn't bear this out. There is actually no direct correlation between government budget deficits and either high interest rates or inflation. Of course, there might be an indirect relationship—political pressures to finance deficits by monetary expansion—but a simple statute reforming the Federal Reserve System could fix that. The depressing effects of tax increases on economic activity, by contrast, are very real and measurable. If the proposed balanced-budget amendment becomes an easy justification in the future to raise taxes to meet automatic, cost-of-living-adjusted entitlement spending, it will become another constitutional curse like the 16th Amendment.

All things considered, the most interesting issue is why the proposed amendment is so controversial. Very few of the participants in the debate have raised any substantial objections to the amendment (the Keynesian "economic theory" issue is deeply buried in assumptions, rather than being argued directly). But since the amendment would not actually force a reduction in spending, its proponents have a burden of proof: Are they selling a sheep in wolf's clothing? Might it not be a more noble crusade, with ultimately more political impact, to elect to the Congress new legislators who reject the flawed philosophy of social "entitlements"?

Perhaps most to be feared is the possibility that the balanced-budget amendment would be adopted along with some version of the frequently proposed flat-rate income tax, for this combination would make income-tax increases much easier to justify and enact. Beware the appeal in public policy to "rationality" and "fairness"—these are applied by planners and managers in a context that tax-averse individuals should fear.

The new issue of "simplifying" the tax code and making it more "fair" has come along just at a time when government is confronted with the necessity of imposing limits on public-sector growth. These limits are defined by the taxpayers' level of anger and resistance and their willingness to vote against those who increase taxes or bring inflation. The requirement in the proposed amendment that tax increases receive a 51 percent majority in Congress is supposed to provide a focus for voter anger, but only a small minority of individualists would feel the anger if the myth were pervasive that taxes can be "fair" and "equal."

Jim Davidson's argument that a constitutional convention might be better than the current proposal, Senate Joint Resolution 5, is worth serious attention. It would certainly stimulate a deeper look at the philosophy of government and the revenue-transfer process than would a mere ratification by 38 states of something Congress wrote. George Will is correct when he points to the logical inconsistency between public attitudes toward spending and the methods of financing it. Only an intellectual revolution can force the consistency in the direction of lower spending, rather than "adequate revenues" for a balanced budget.

Contributing Editor Joe Cobb is executive director of the Washington-based Choice in Currency Commission and is currently on the staff of the House Banking Committee.

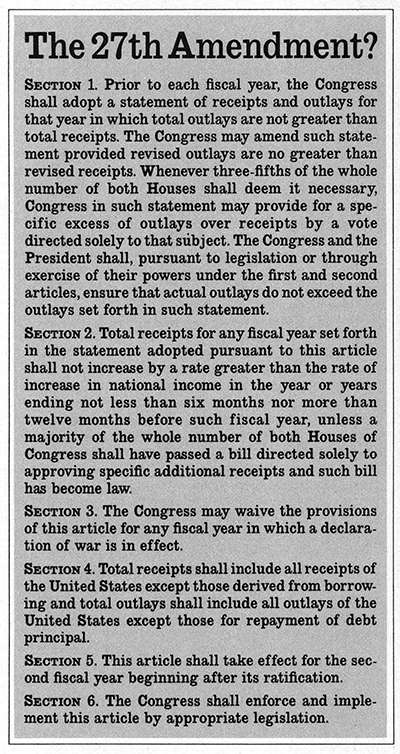

The 27th Amendment?

SECTION 1. Prior to each fiscal year, the Congress shall adopt a statement of receipts and outlays for that year in which total outlays are not greater than total receipts. The Congress may amend such statement provided revised outlays are no greater than revised receipts. Whenever three-fifths of the whole number of both Houses shall deem it necessary, Congress in such statement may provide for a specific excess of outlays over receipts by a vote directed solely to that subject. The Congress and the President shall, pursuant to legislation or through exercise of their powers under the first and second articles, ensure that actual outlays do not exceed the outlays set forth in such statement.

SECTION 2. Total receipts for any fiscal year set forth in the statement adopted pursuant to this article shall not increase by a rate greater than the rate of increase in national income in the year or years ending not less than six months nor more than twelve months before such fiscal year, unless a majority of the whole number of both Houses of Congress shall have passed a bill directed solely to approving specific additional receipts and such bill has become law.

SECTION 3. The Congress may waive the provisions of this article for any fiscal year in which a declaration of war is in effect.

SECTION 4. Total receipts shall include all receipts of the United States except those derived from borrowing and total outlays shall include all outlays of the United States except those for repayment of debt principal.

SECTION 5. This article shall take effect for the second fiscal year beginning after its ratification.

SECTION 6. The Congress shall enforce and implement this article by appropriate legislation.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Balancing Act."

Show Comments (0)