Trends

FCC Takes Back Seat to Editors As previewed last month in these pages (see REASON's interview with FCC Chairman Mark Fowler, Nov.), the Federal Communications Commission has voted to ask Congress to abolish the so-called Fairness Doctrine and the equal-time provision. "Today we strike a blow in the cause of freedom," Fowler told reporters. "This is the time to strike down government's role in determining what the people shall hear and see.…I would rather have the editor make these choices than the government."

The Fairness Doctrine requires broadcasters—unlike print media—to give "reasonable opportunity for the discussion of conflicting views on issues of public importance." The equal-time rule requires broadcasters to give equal opportunities to all candidates for an office if it allows use by any of them. The commission also voted to ask Congress to repeal a provision requiring stations to sell "reasonable" amounts of time to candidates for federal office. Immediately after the FCC's vote, a coalition of consumerist, religious, and labor groups announced the formation of Friends of the Fairness Doctrine to lobby for retention of the government controls.

The idea that these provisions violate the First Amendment was first brought to national attention, as far as we're aware, by our own senior editor, Tibor Machan. In an article called "One-Sided Fairness" that appeared in Barron's on April 22, 1968, Machan traced the history of the doctrine, illustrated its contradictions, and pointed out that government ownership of the airwaves is the fundamental problem. That bridge, however, has yet to be crossed.

Flunking the Graduated Income Tax In his "Open Letter to the President" (May) REASON Taxes columnist Tim Condon lambasted the progressive income tax and suggested two less painful alternatives: a tax on consumption and a flat-rate tax of about 13 percent. Well, it seems these ideas are at least being discussed these days in Washington.

In an interview with the Baltimore Sun (Aug. 4), Paul Craig Roberts, assistant Treasury secretary for economic policy (and a REASON contributor) said, "There will be some consideration given in this administration to a flat income tax without exemptions or deductions and maybe even to moving away from income taxes altogether to a consumption tax." Roberts mentioned a figure of 15 percent as the flat-rate tax.

Roberts's boss, Treasury undersecretary for tax and economic policy Norman B. Ture, had also criticized the progressive income tax before taking office. (The same Sun article, however, reported that Rep. Jack Kemp (R-N.Y.) is opposed to a flat-rate tax and is working to lower the maximum graduated tax rate to 35 percent.)

What supply-side economist Arthur B. Laffer would prefer is a value-added tax combined with a "very mild…income tax." Laffer calls income taxes "very inefficient methods of collecting revenue to finance government service."

Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Jerry Hausman has found that the figures support all the criticism of a progressive income tax scheme. In a recent study published in the Brookings Institution's How Taxes Affect Economic Behavior, Hausman reported that "the economic cost of a progressive income tax is higher than most previous studies have indicated." Hausman estimates that a flat 15.4 percent rate, with a $1,000 exemption per family, would raise the same amount of tax revenue as the graduated tax system does presently.

Meanwhile, Rep. Philip Crane (R-Ill.) indicates that he may introduce legislation to replace the progressive tax system with a flat rate.

Medical Advertising Spells Relief When in late 1979 the Federal Trade Commission ordered the powerful American Medical Association to lift all restrictions on doctors' advertising, there were widespread worries that hucksterism would prevail because, supposedly, business concerns would override medical ethics. On the contrary, we find, one particular service now being promoted would seem to prove the benefits of advertising to the medical consumer.

The service is called Gericare, and it consists of a network of doctors who treat elderly patients at a discount. Gericare doctors only collect what Medicare is willing to pay based on its fee schedules. Going to any other doctor, patients often end up paying from 20 to 60 percent of their bills.

While some of the motivation is a genuine concern for the elderly, another factor is declining patient clientele as physicians proliferate and hospitals pose new competition with the opening of outpatient clinics. As one doctor who joined Gericare put it in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, "I could see that down the road the hospitals' doctors would have an edge in attracting patients." Since he joined Gericare, Dr. Douglas Whitehead says, his practice has expanded, and he no longer worries about competition from hospitals.

An expanded practice is also the byproduct of a similar discount for elderly patients offered by another New York firm, Geriatric Care Associates. According to founder Paul A. Lavinger, an internist, the practices of some of his 40 associates have grown by as much as 20 percent. Some 700 patients have benefited from the medical discounts offered by this clinic alone.

FTC Catches Deregulatory Fervor Feeling the heat from a deregulation-minded Congress and an administration that had threatened to abolish its antitrust branch, the Federal Trade Commission has dropped two of its major antitrust cases. Both had become symbolic of the agency's domination, in the 1970s, by consumerist influence.

The first case involved the FTC's novel theory of "shared monopoly." According to this theory, it doesn't take a single firm to have a monopoly. Instead, when most of the business in an industry has been won by a few firms, they are alleged to be harming consumers by smothering competition and charging premium prices. Using this theory, the FTC in 1972 charged the four leading cereal producers—Kellogg's, General Mills, General Foods, and Quaker Oats—with the shared monopolizing of 90 percent of the cereal market. (Quaker was subsequently dropped from the case.) The proposed remedy was to break up the companies and allow any and all firms to use the big four's trademarks and recipes. Thus, anybody would have been able to produce Froot Loops or Cap'n Crunch, not just those who had spent the money developing and marketing them.

On September 9 an FTC administrative law judge dismissed the case, ruling that the staff failed to prove that the three companies had engaged in price fixing or that they had conspired to avoid adding nutrients to cereals; moreover, he noted evidence of competitive activities in the form of cents-off labels and premiums in cereal boxes. Congress, meanwhile, is considering legislation that would forbid the FTC from using the shared-monopoly theory as a basis for antitrust action.

Just a week later the FTC's commissioners voted unanimously to drop the agency's largest-ever antitrust case—an eight-year-old suit against eight major oil companies. That case, also considered to be breaking new ground in antitrust,charged possible price conspiracy by the oil companies and sought to break them up into separate production, pipeline, refining, and marketing companies. Most economists have concluded, by contrast, that the oil industry is highly competitive and that integrated operations tend to promote efficiency.

The oil company case had been marked by the largest subpoena ever issued, totaling 1,800 pages (plus 140 errata pages issued a month later). Exxon alone estimated that compliance would have required 6,752 man-years, leading to 93.5 million pages—a pile of paper 9.8 miles high. An administrative law judge forced the FTC staff to back down, resulting in a more modest (but still massive) request for data. And although the case is now dropped—so that the agency can focus on "initiatives more likely to provide benefits to the public"—the FTC is keeping all the documents on file for future reference.

When Controllers Go Uncontrolled Suppose you're an air traffic controller. The job is stressful, unquestionably, and sometimes it really gets to you. One day you discover that if a doctor certifies that you have a "psychological disorder," you can retire with tax-free disability compensation that exceeds your normal take-home pay. Even if you're completely honest, that's bound to be an incredible temptation.

It turns out that large numbers of controllers apparently have succumbed to that temptation. When the feds changed the disability rules in 1974 to allow government employees to select their own physicians when making disability claims—opening up the opportunity to shop for sympathetic doctors—the incidence of new psychological disorders among controllers jumped by 150 percent, compared with an increase of only 23 percent in other disorders.

That was among the findings of a study by Michael Staten of the University of Delaware and John Umbeck of Purdue University, funded by the Carthage Foundation. The authors used the example of air traffic controllers to support their thesis that, as insurance benefits increase, claims escalate while the likelihood of catching invalid claims decreases.

Another recent study, by the Federal Aviation Administration itself, compared the incidence of various disorders among controllers with that of other populations. Among its findings were that controllers actually have a lower incidence of coronary heart disease (presumably a stress-related malady) than the population of adult males as a whole. The FAA study did find that psychiatric disorders among controllers were more frequent than among Navy personnel, but prior to the 1974 rules-change the difference was not large—6.9 per thousand for Navy personnel versus 8.6 per thousand for controllers. After 1974, however, the reported psychiatric disorder rate among controllers soared to 21.5 per thousand.

Thus, the popular image of air traffic control as a uniquely stressful job—one which perhaps requires uniquely high compensation—seems to be unsupported by the evidence. An additional indication that perhaps controllers may be overpaid is the deluge of applications for controller jobs received by the FAA since the start of the controllers' strike.

Paying for Water All across America, people are beginning to realize that water supplies can no longer be taken for granted. Many urban areas are experiencing water shortages, and growing numbers of urban water systems are beginning to crumble due to inadequate maintenance. In rural areas, ground water supplies are being depleted in Arizona, California, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Why? In a nation where such necessities as food and clothing are supplied in abundance, why should we suffer from shortages of life's most basic necessity? The answer is that most water is supplied by government entities, rather than the marketplace. Because these entities are controlled by political, rather than marketplace, constraints, they typically price water at far less than its value, thus ensuring support from well-organized interests. The results are quite predictable: (1) much water is wasted—for example, 75 percent of all US farmland is irrigated by wasteful surface methods rather than by water-conserving drip irrigation; and (2) insufficient funds are generated to adequately maintain and replace the water systems as they wear out.

Fortunately, these problems are starting to be acknowledged by people who can do something about them. Last March the General Accounting Office published a report on six federal water projects in the West, including California's huge Central Valley Project. Water prices are so low that they recover only eight percent of the cost of these projects, the GAO concluded, leading to billions of gallons a year being wasted. It recommended that Congress withhold approval of any new projects until more water-conserving pricing is adopted.

Interior Secretary James Watt is winning a few cheers from environmentalists for taking a hard-line stand on water pricing. The contract of the Westlands Water District for water from the Central Valley Project is up for renewal, and Watt wants to raise the $8 per acre-foot price to the cost-of-delivery price of $11.80—and build in a periodic price adjustment, rather than signing the flat-rate 40-year contract the district wants. Sierra Club water specialist Rose McCullough lauds such efforts, pointing out that "If we had cost-recovery to screen out the uneconomic [projects], we'd be 90 percent of the way to getting rid of environmentally unsound ones.'' The Reagan administration has also introduced legislation to provide for full cost recovery for inland waterway projects via user fees—a move Brent Blackwelder of the Environmental Policy Center calls an "unprecedented reform."

The same pricing principles should be applied to urban water systems, suggested Steve Hanke, senior economist for the Council of Economic Advisors, in a Wall Street Journal article (Sept. 3). Pointing out that both private and public water systems are in trouble because of politically controlled prices, Hanke urged that the water industry be privatized and deregulated. "Each city or service area," he suggested, "would award a contract or franchise to the private firm that would guarantee, at the lowest price, a specific quality of service over the length of the franchise." France, he pointed out, has used such a system for many years. As a result, French water systems provide high-quality, efficient service, and the French water companies "have been among the world's leaders in technological and management innovations." As the old saying goes, you get what you pay for.

Radiation Reexamined The controversy over the effects of low-level radiation continues in the scientific community. One of the principal sources of data on such effects has been the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Detailed long-term studies on these populations have led to many of the standards for radiation exposure in use today. But the studies have failed to reveal the shape of the "dose-response" curve at very low levels of radiation. Is it linear, such that any amount of radiation, no matter how small, still produces some harmful effects, or is there a threshold below which radiation is harmless?

One new study was reported recently in Science (Sept. 11). Three researchers (two Americans and one Japanese) studied the incidence of four types of genetic effects in the children of A-bomb survivors. Comparing the rate of occurrence of each effect with that produced by spontaneous mutation, they found no clear statistically significant effects. They also used the data to produce a new estimate of the "doubling dose" in humans—that is, the amount of radiation necessary to produce a 100 percent increase over the spontaneous mutation rate. Their result: 156 rems, which is four times higher than the estimate in current usage based on studies in rats. (In other words, the existing standard may be overly cautious.) While still considered preliminary, the finding lends further support to the hypothesis that there may be a threshold dose below which radiation is harmless.

Even more startling is the evidence in a 222-page volume, Hormesis with Ionizing Radiation, by biochemist T.D. Luckey (CRC Publishing Co., 1980). As reported in Petr Beckmann's Access to Energy newsletter, the book reviews some 1,200 references bearing on the hypothesis that low levels of radiation actually have positive effects. The term hormesis refers to the principle that small doses of poisons are stimulatory. While an accepted principle for chemical and biological toxins, the idea had not previously been applied to ionizing radiation. Luckey's book provides considerable evidence that low levels of ionizing radiation may well be beneficial for various physiological functions and may even be essential to life. (We live, after all, in a continual bombardment of background radiation from natural sources.) All of which further strengthens the case against the linear hypothesis—and those who would use it to ban all uses of radioactive materials.

Natural Gas Decontrol: How Much, How Soon? Opponents of decontrolling all natural gas prices make the following argument: since the Natural Gas Policy Act (NGPA) already provides for gradual decontrol of the price of gas discovered since 1977—and complete decontrol of that gas by 1985—all that decontrol of "old" gas would do is provide windfall profits for gas producers, at the expense of hapless consumers, while not increasing gas supplies.

What this argument overlooks is that most "old" gas wells are not owned by isolated individuals. In fact, they are mostly owned by oil and gas companies that own a mix of old and new wells. The more profitable each company's total operations, the more it can afford to spend on the costly business of exploring for new sources of supply.

Is that just corporate propaganda, or is there empirical evidence to support that proposition? Well, since the decontrol of oil prices, starting in 1979 and completed by President Reagan's removal of remaining controls last January, oil exploration has, in fact, soared. In 1981 the oil industry in this country spent $30 billion on exploration, nearly double the 1979 figure of $15.8 billion, according to figures compiled by Oil & Gas Journal. Spending on production (actually bringing up oil from known fields) has increased by 55 percent, to $16.5 billion this year, over the same period. According to an in-depth assessment by New York Times reporter Steve Lohr last August, new oil rigs are being put up at the rate of nearly four a day, "a 50 percent increase within just a few months."

''Without the higher prices, we couldn't have been nearly so interested in the Overthrust Belt," explained David F. Work, regional exploration manager for Indiana Standard, which owns 60 percent of Anschutz Ranch East, the largest oil find since the Alaska North Slope. "The strong prices allow you to justify the expensive technology and the big upfront costs of going after oil and gas out there"—typically at depths exceeding 15,000 feet.

Would consumers, nevertheless, be harmed by gas price decontrol? Actually, the only question is over the pace of decontrol, since the NGPA is already decontrolling gas prices. A recent study by Data Resources, Inc., predicts that accelerated decontrol starting in 1983 and ending all controls by 1985 would prevent a drastic price rise in 1985 (under NGPA) in exchange for more moderate increases in 1982 through 1984 and slightly lower prices than under NGPA from then on out. That is in part because accelerated decontrol would (a) expand gas supplies sooner, (b) encourage more conservation measures sooner, holding down demand, and (c) prevent a huge surge in prices in 1985, which could go well beyond free-market levels if up to half of all gas (the "old" gas) remains at controlled prices when all controls are removed from new gas, as NGPA provides.

Thus, some acceleration of gas pricing decontrol seems quite likely. The debate will not be over whether to do it but simply over the details.

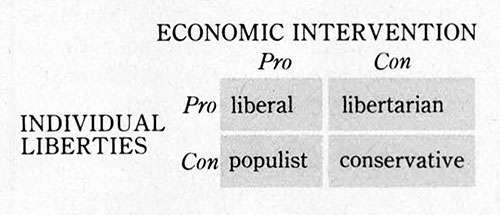

Political Labels For a New Age In our March issue, we mentioned the new schema of political belief systems proposed by political scientists William S. Maddox and Stuart A. Lilie of the University of Central Florida: populist, conservative, liberal, and libertarian. We said that we hoped these more accurate labels would replace the outmoded categories so beloved by pollsters, politicians, and the mass media: liberal, moderate, and conservative. Now, the results are out from a more extensive study by Maddox and Lilie, sponsored by the San Francisco-based Cato Institute, and some influential people have taken notice.

Conservative political analyst Kevin P. Phillips wrote in his nationally syndicated column recently that the more precise division into four ideologies has not been picked up by pollsters or politicians because "prevailing political and economic interests are served by the old liberal-conservative terminology and disserved by the four-category expansion." While the liberal-conservative descriptions are keyed to economic issues and government power, noted Phillips, the newer labels take personal behavior and moral issues into account. The main proponents of this moral aspect, he says, "albeit from different perspectives," are the Libertarian Party and the New Right.

Liberal Democrat Alan Baron, meanwhile, also lauded the Cato Institute study in his Baron Report. The four groupings, Baron said, "better reflect public attitudes." Baron reported that of the 70 percent who were consistent on at least five of the six economic intervention and civil liberties questions asked, 24 percent were populists (against the expansion of individual liberties and for government intervention in the economy), 18 percent were conservatives (against both), 16 percent were liberals (for both), and 13 percent were libertarians (for expanded liberties and against government intervention).

Louisiana Schools: Deregulation Update The latest word from Louisiana State Rep. Woody Jenkins, who authored a 1980 bill deregulating private education in Louisiana, is that deregulation has been a success. Over the past 12 months, he says, over 100 new private schools have been opened in that state.

The law now lays down only four requirements for private schools that receive no state or federal funds: the schools must have a physical facility, teachers, pupils, and a 180-day annual schedule. And instead of having to meet state government standards, the teachers must meet the standards set by the board or church operating the facility.

The real requirements facing the new schools are now those of the parents who pay them to educate their children. This allows for great diversity in the particular emphasis and beliefs taught by the different schools, including that touchy topic, religion.

Before the Jenkins bill was passed, the state defined a school as an institution having at least 50 pupils and state-certified teachers. Under Louisiana's compulsory attendance laws, parents who taught their children at home, for example, were liable to prosecution.

Milestones • Diminished Defense. As "of January 1, California's accused will no longer be able to take the infamous "diminished capacity defense" successfully used by former San Francisco official Dan White to excuse his murder of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk—if it passes constitutional challenges.

• Federal Grass Bill. Reps. Stewart B. McKinney (R-Conn.) and Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) have introduced a bill that would legalize the use of marijuana for medical purposes, e.g. by cancer and glaucoma victims. Some 32 states have already passed laws allowing such medical use. This bill would establish a single federal program for the cultivation and distribution of government-grown marijuana.

• Synfuel Funding Freeze. The US Synthetic Fuels Corporation, created by the government to assist synfuel development, may receive no funding beyond the $13 billion it has on hand. (Some $66 billion was originally to be added.) Chairman Edward Noble told a House subcommittee that the Reagan administration wants to end federal funding as early as 1984.

• Nuclear World Expanding. China has launched three new reconnaissance satellites that seem to assure early-warning signals against Soviet attack and retaliatory capability. The successful multiple send-off by a single rocket also demonstrated China's ability to launch multiple-warhead intercontinental ballistic missiles across a range of about 6,200 miles, as shown in tests last year.

• Senate Cuts Farm Subsidies. The Senate passed a four-year farm bill much along administration lines. (The House had not voted on its own version at press time.) The Senate bill's $10.8-billion price tag, although $1.8 billion more than recommended by the administration, is $2 billion less than urged by the Senate Agriculture Committee and many more billions less than lobbyists would have liked. Wh!le the bill would reduce dairy price-support spending by 45 percent and restrict grain storage at taxpayer expense, sugar import fees would be raised and a new government loan program for sugar processors created.

• Gene-Splicing Safe. A National Institutes of Health federal advisory committee has concluded that most gene-splicing experiments are safe and that federal regulations in effect since 1976 should be dropped. The NIH expects to make its final decision in January, after public comment is heard.

• Acid Rain Report. A General Accounting Office interim report indicates that, despite marked disagreements between participating scientists, the tentative consensus is that acid rain is not a health hazard to people (see Trends, Jan.). The report did acknowledge some increased acidity in certain northeast and midwest waters, primarily caused by acid rain and causing some damage to aquatic life.

• Gold Standard Sentiments. Rep. Jack Kemp (R-N.Y.) recently polled viewers on the gold standard during a show on the television station QUBE, a Columbus, Ohio, station that allows viewers to talk back to their TV sets. The verdict: 84 percent in favor of a gold standard; 16 percent opposed.

• Banking Bills. Surprisingly, sentiment favoring a major banking deregulation bill has been on the upswing in Congress lately. Antiquated banking laws (see Trends, Nov.) may be dumped in favor of allowing savings and loans associations to increase their services to better compete with commercial banks and revoking the Glass-Steagall Act barring banks from investment banking.

• Local Power Curbed. A US District Court in Chicago ruled that the village of Bellwood could not require that real estate agents get an okay from city council before soliciting listings. The Illinois Association of Realtors had cried foul and won on the basis of free speech rights. The city council said it was only trying to curb panic selling and to assist racial desegregation.

• Rent Control Results. A Rand Corporation study commissioned by the Los Angeles City Council concludes that rent control may help tenants in the short run but "create(s) the very housing shortage it was designed to alleviate" in the long run. The study reports that landlords clearly reduce maintenance costs to compensate for rental revenue lost and found that Los Angeles does not have a housing crisis—"a tight market, but not a crisis." The council will soon decide whether to extend Los Angeles's three-year-old rent control law past its May 15, 1982, expiration date.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Trends."

Show Comments (0)