Stock Market Returns

Common stocks represent real assets as much as do oil, metals, and real estate-and the data suggest they're a good buy today.

"The beginning of this decade certainly does not look auspicious. The omens are just about as bad as they were at the end of 1969, if not worse. This is no longer the season to be jolly. It is damn serious and we better have no illusions about it." So columnist Heinz H. Biel lectured readers in Forbes's first issue of the new year. Even though Mr. Biel is right, there's reason to be jolly—since 1969, a lot of folks have come to the same conclusion he has, and they've been taking adaptive action. The marketplace may not be efficient every day, but it certainly is by the decade.

The doomsday scenario is well known. Contrary-opinion practitioners should be looking at the stock market. Today the debates center on inflation accounting, investment incentive, getting corporate returns on equity up, cutting taxes, raising savings rates, adjusting taxes for inflation, and deregulating business. There is now hope and some action. There was neither in 1969. The 1980s look better for stocks than the decade just past.

I am here to follow up on my piece that appeared in REASON's June 1978 financial issue. In that article, I pointed out the good relative value showing up in the stock market and painted a bullish scenario into the mid-'80s. Rising intrinsic and relative values in stocks, positive changes in public attitudes, a favorable stock market cyclical environment, rising institutional and foreign buying power, and the general disillusionment with stocks formed the foundation for optimism. The article concluded on this note:

But while the millennium probably has not arrived, there nevertheless appears to be an excellent opportunity brewing right now in US equity markets. No other major country's economy or market looks as promising. When the time comes for holding shares of industrial enterprises, it would be a sorry commentary…if free-market believers were still off in the woods gathering nuts and berries.

That was heresy at the time it was written (early 1978). Today this thesis has become the center of serious debate in the investment community, with vigorous advocates on both sides. So let's review the case for stocks in today's environment.

Contrary to general expectations, there was no recession in 1978 nor in 1979. Real growth continued to be generated, although at steadily diminishing rates of increase. The deterioration process for the economy has been slow. The incredibly bad behavior of the Federal Reserve Board during 1978 and 1979 accounts for the new high inflation and interest rates achieved in 1979. Consumer confidence levels deteriorated in 1978 and collapsed in 1979. Inflation-adjusted corporate earnings probably rose in 1978 and probably fell in 1979—inflation adjustment is imprecise. Corporate dividend growth outpaced inflation in both 1978 and 1979.

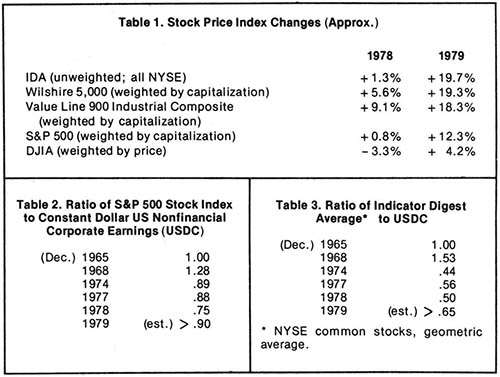

Against that background, how did stock prices do? Remarkably well—especially if the recession many expect is right around the corner. Table 1 shows the results for several stock price indices. While risks have risen with stock prices since early 1978 and inversely with the decline in the economy's vigor, a strong case for common stock investing can still be made.

WHERE STOCKS ARE HEADED

The doomsday litany is well-known. Earnings and profits are up sharply for the prophets of gloom and doom. Scary seminars are a booming business. The evening news carries the price of gold. The public's confidence has already fallen sharply. This isn't to say that attitudes can't get worse; they can. It merely means that the marketplace is not dominated by starry-eyed dreamers unaware of the very real political and economic problems the market faces.

Stock prices still look reasonable compared to earnings. Table 2 plots the ratio of Standard & Poor's 500 stock price index over the Commerce Department's computation of constant-dollar earnings for US nonfinancial corporations. They are not fully comparable. They are, however, as good an approximation as we're likely to get until the constant-dollar earnings numbers that will be coming out soon for many large companies can be put together for some major market average. The earnings numbers are approximations only. They are a crude form of inflation adjustment.

Table 3 makes the same sort of comparison, using the Indicator Digest Average (all NYSE, geometric average, unweighted) instead of the S&P 500. In both cases, at the end of 1978 stock prices do not appear high compared to purchasing-power-adjusted earnings. Stock prices, however, were up and constant-dollar earnings probably down some in 1979. Therefore, whatever "undervaluation" may have existed at the beginning of 1979 surely diminished somewhat by the end of the year.

Central value computations suggest that stocks in general are reasonably priced. Using (a) book values, (b) normalized earnings, (c) implied growth rates, (d) dividend yields, (e) trend inflation rates and bond yields, (f) historical price-times-earnings (P/E) ratios adjusted for inflation, and (g) regression formulae utilizing historical relationships and estimates for next year's results, stocks in general seem priced at or somewhat below "central value." Expected growth for the Dow Jones Industrials is subnormal and has been for some time. They have been (and are) especially vulnerable to a hostile political environment. They are cyclical and highly visible. Many of their markets are in slow-growth areas. Nevertheless, our estimates of central value for the DJIA in 1980 fall in the 865-885 range, right about where they are at this writing.

Less-mature large companies are estimated to have central value levels 15 percent above the DJIA's P/E ratio. For the sort of growth most investors should be looking for today, at least a 28 percent premium over the DJIA may be expected at central value levels. In general the DJIA looks centrally valued, the typical large company slightly undervalued, the good smaller growth companies somewhat undervalued, and small high-technology companies clearly overvalued. On balance, the values for the next several years look quite reasonable—not cheap, but reasonable.

A sharp market decline would be required to produce many truly undervalued situations. Such a decline would also establish a bullish washed-out psychological condition that presently does not exist in the market with the DJIA in the mid-800s. The DJIA at 650-700 would probably accompany such a condition. A Federal Reserve-induced credit squeeze would be the likely prime mover for such a market break.

BUSINESS HELP

Corporations are adjusting to inflation. Freer interest rates have combined with financing ingenuity to permit more facile management of corporate financial needs. Items such as overnight repurchase agreements have become widely used. More-flexible money markets have permitted corporations to function with lower cash balances.

Inventory management has improved. More and cheaper computer power has been the key here. Companies can function with less capital tied up in inventory. A feature of the 1975-to-date economic expansion has been tighter inventory control.

Escalator clauses are getting into all kinds of contracts. Fewer companies are getting boxed into fixed-price contracts where inflation may eat them alive. Pricing policies are getting better. Once again, computers are helping management respond faster to the need to raise prices to offset cost increases. Companies are coming to realize that cost increases can be large and permanent.

Accounting practices are more and more seeking to show inflation's effect. The outcome here may be less taxes paid (as in shifts to LIFO inventory accounting), more realistic earnings reports, heightened corporate realization of inflation's effects, and increased political pressure for lower taxes. Efforts at inflation accounting are also showing that manageable debt is a good thing to add to the balance sheet when inflation is expected to persist.

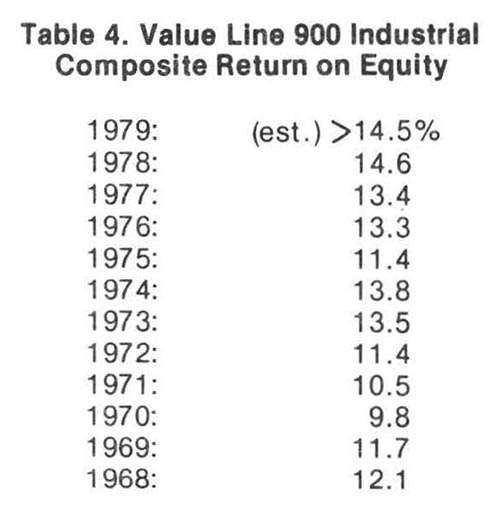

Return on equity is becoming the major focal point in corporate planning. Maintaining it is the basis for sustainable corporate growth. It is a tough job when inflation is accelerating. A company's capacity to raise prices without getting attacked by the government, beaten by the competition, or having its market shift to a substitute product is essential. Having a separate market niche and being the low-cost producer of a product are often crucial. More and more companies are emphasizing return on equity and doing a better job with it than they did 5 or 10 years ago. Table 4 shows the return on equity for the Value Line 900 Industrials, dominated by large corporations. And for all corporations, return on equity rose from 12.4 percent in the first quarter of 1978 to 18 percent in the second quarter of 1979. Net margins on sales rose steadily to a 6.1 percent rate in mid-1979. These are both above the averages for the past decade.

Corporate stock prices, earnings, and dividends have a good record against inflation. Prior to 1968 it is clear that stocks delivered a sizable advantage over bonds, other fixed-income media, and the inflation rate. From the end of 1968 through the end of 1978, stock prices did rather poorly on all counts. Stocks were clearly overvalued in 1968. Rising inflation demands a higher discount rate and hence a lower general market P/E ratio. That pushed total stock market returns down sharply.

Nominal earnings and dividends held their own, however. Using the Value Line 900 Industrial Composite statistics, nominal earnings, deflated by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), scored a 29 percent gain for the 10-year period. Dividends, deflated by the CPI, increased 4 percent—nothing to brag about, but better than some people realize. It is true, of course, that inflation does cast some serious doubt on the reality of the earnings numbers themselves. Simple deflation by the CPI is not a complete or adequate adjustment for inflation's effects on profits.

Between 1968 and 1974, the market really discovered inflation. That was the shock period. We now seem to be in the period when P/E ratios are stabilizing somewhat in reasonable areas. Earnings and dividends should play a somewhat larger role in equity returns from here forward (barring a hyperinflation), and that would be good news.

THE STOCK OPTION

The flight from paper currencies continues. In fact, it is accelerating. A good deal of the present mania is a product of foreigners' political fears, as in the Mid-East. Nevertheless, more and more people are discovering inflation and its effects. A dollar one year hence is no longer a dollar. It no longer serves as a storehouse of value. A half-century of thrifty tradition is going down the tubes. Consumer credit is rising relative to incomes. Personal saving fell below 5 percent in 1979. In only four years since 1946 has it been as low. Unlike pre-1976, the consumer is now betting on the continuation of inflation. Defenses are houses, gold, buying now, borrowing, and money market funds.

The avalanche of money that has moved by the billions into money market mutual funds is testimony to the awakening among investors. Soon they will realize that that money isn't going to keep up with inflation on an after-tax basis there, either. These investors will eventually be drawn to equity ownership of profit-earning assets. Lending is a loser's game for taxpayers in an inflationary environment. Too many competitors are tax-free institutions that can offer better terms, in larger volume, than can the individual taxpayer.

Inflationary momentum is great. It is likely to persist at high rates, though it may stabilize somewhat this year. In a presidential election year it is questionable whether the Fed will jam on the monetary brakes. If they do not, the flight from currencies will continue. Stocks will be a beneficiary. A recent Wall Street Journal article noted that "frantic precious-metals buying overseas has ignited an equities-buying spree on the Tokyo Stock Exchange as Japanese investors try to hedge against inflation." That takes on added significance when we realize that P/E ratios in Tokyo are already over 20, versus around 8 in the United States.

Common stocks represent assets and real values as much as do oil, metals, and real estate. Reading many discussions of inflation hedges would leave you with the idea that common stock certificates were little more than personal IOUs from the Flim Flam Man. Some are; most are not. Some coins are counterfeit, too. The assets and earning power behind a stock certificate are quite real. No matter the real asset you want, there are usually available plenty of stocks backed up by that particular item as an earning asset, not just a "rustable." In early 1980 metals and oil are the big deal; later in the year it may be something else. And not all worthwhile assets have to be things you dig out of the ground. A fine marketing organization is worth plenty any time. Of course, if the monetary brakes are applied, the most popular inflation-hedge assets will likely fall in price.

Corporations engage in a value-adding process as they manage assets. Good management is what gives the stock owner the chance for returns above the rate of inflation. You don't get that with ownership of only the tangible asset itself. There is no going-concern value in an ingot of silver. It takes fear and panic or just plain tomfoolery to obtain a longer-term rate of return above inflation by putting a tangible asset (comic books?) in your attic.

Common stocks are more convenient, have lower transaction costs, and are less risky for most individuals than are most other investment vehicles. Bid-asked spreads are narrow. Liquidity is good. Diversification is easier, since ownership interests are divisible. There is considerable information available about the businesses the stocks represent. Commissions are low. Fraud risks are low. At least all this is true compared to most direct-ownership or other esoteric inflation hedges.

STOCKS: GET IN LINE

Massive buying power has accumulated on the sidelines. Through 1977 and 1978 institutions ran up large cash balances. Common stock mutual funds were running over 10 percent of assets in cash. Merrill Lynch surveys showed 14-16 percent cash positions for institutional investors. For 1978, it is estimated that only 17 percent of all new money coming into private pension funds was invested in common stocks. That was down from 50 percent in the early 1960s and over 100 percent in 1971-72. The flight from equities has been sizable. Stocks are now estimated to be only 55 percent of pension fund assets. Bonds make up most of the rest.

That is already changing. In 1979 new pension money went into stocks at around a 50 percent rate. The Merrill Lynch survey for the fourth quarter of 1979 shows about an 11 percent cash position for institutions. That is still historically high but down from last year.

And now GM, in what augurs to be an important move, instructed its pension managers in late 1979 to shift their pension investing from 50 percent stock and 50 percent bonds to 70-30 in favor of stocks. And it's about time. Fixed-income securities during inflation could not help GM reduce its contributions to its pension funds. Common stocks may.

Institutional managers have been hiding in stock index funds, bonds, option writing, or anything else that would let them recover from the 1973-74 slaughter they endured in stocks while inflation was being discovered. Now they are coming out of their bomb shelters to fight back. As the GM decision highlights, the clients are goosing their managers along. So now the hard evidence is beginning to appear in support of our early 1978 thesis. A revolt among the beneficiaries of "fixed income" contracts such as some pensions, and most life insurance, may hasten the move from bonds to stocks.

The rationale isn't difficult to follow. Earnings and dividends grow. Bonds move in the opposite direction from inflation. Their interest payments do not grow. Inflation grows.

This outlook is nowhere near a universal one on Wall Street. Many institutions are still busy trying to time their purchases in the bond market. That's like chasing the greased pigs at the county fair—it may be fun, but it is messy and not very productive.

Those pension fund bonds just sit out there doing nothing for the corporate pension fund sponsor. In fact, they may offset some of any inflation advantage the company may have otherwise gained from being a net monetary debtor.

The huge increase in money market funds is clearly, in part, a build-up of individuals' buying power. Eventually, much of it is likely to be tempted into equity ownership as inflation grinds away on the taxable individual.

Finally, there are the foreign investors. As the electronic age arrives, all major investment markets are becoming international. Prices are not only being set "at the margin," but increasingly that margin is controlled by flows of foreign investment funds. The Securities Industry Association reports that over the past five years foreign buying has accounted for 20-25 percent of net purchases of US stocks. Such buying activity tends to parallel the performance of the US dollar against other major currencies. The dollar made a low in October 1978 that has not been breached to date on a trade-weighted basis. And as international political turmoil increases, the relatively safe and relatively self-contained US markets are likely to become more attractive to foreign money.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGES

The value of common stocks relative to other investment vehicles is rising. Many "inflation hedges" have done admirably over the past five years. Insofar as they have advanced well in excess of price inflation, most of them are likely priced over their "intrinsic value." Take gold and single-family houses as examples.

Is an ounce of gold really worth 150 bushels of wheat? Perhaps. Or maybe wheat is underpriced. But at current levels, gold clearly has turned into political turmoil insurance more than the sensible inflation hedge it used to be. As Milton Friedman assessed it recently, if gold were priced solely on the basis of US monetary mismanagement, it could be in the $200-$225 range, and not at the $700+ level. That seems reasonable.

The single-family house has been a great inflation defense, but it has been rising in excess of the inflation rate for quite a long time now. That cannot be justified on any intrinsic value basis. Relative to stock prices, there have only been three other times in the past 100 years that stocks looked so good relative to houses: 1894, 1921, and 1949. Nor is real estate a one-way street. Consider LaSalle Street in Chicago's financial district: 1919: $100/sq. ft., 1967: $69, 1977: $138. Or take Chicago's State Street (that "great" street) in the downtown area…please! 1929: $170/sq. ft., 1967: $145, 1977: $122.

Value-oriented investing is returning to favor. The beating taken by investors in the early 1970s has prompted a relative return to more fundamental investment valuation techniques. There is still a lot of herd-following going on, but the resurgence of value investing, while it lasts, works toward more rational pricing in the stock market, and that's bullish for longer-term, value-oriented investors.

Corporations continue to show the way with their acquisitions of other companies. While other reasons intrude on the decision to acquire, the corporate takeover spree is undoubtedly prompted in large part by the belief that the earning power of many publicly traded companies far exceeds the prices their stocks command in today's market. These decisions are being made by the same managers who are still letting their investment advisors put bonds in the company pension fund. Many of them are likely to follow GM's lead toward more stock and less bonds.

High expectations are drawing plenty of stock buyers. Despite the gloom and doom and the sluggish DJIA, the market moves when expectations rise. The booms in high-technology issues and energy stocks have been notable. Many stocks here already appear overvalued. Fear rather than solely greed seems to be a prime mover in today's market. But a mover it is; witness the mining and defense stock gains during late 1979 and early 1980.

The point here is that, as an understanding of equity values reaches more investors and fear of inflation grows, fuel for the market will be forthcoming. The stock market is not dead. But neither is it particularly efficient in recognizing value beyond next month. Random-walk/efficient-market proponents to the contrary, such values exist.

UPSIDE FACTORS

Cyclical market trends are positive. Five out of seven selected identifiable stock market cycles of four years' duration or more appear to be headed up at present. These cycle calculations are crude and imprecise. Their causation is unexplained. But with the recent popularity of the 50-year Kondratieff Wave, which is said to be pointed down, it seems appropriate to point out that the cyclical picture for 1980 and 1981 looks rather good.

Social and political attitudes in the United States are continuing to change positively for investors. This is a long-term element. The momentum still remains with those who favor more government rather than less, but they have lost the initiative in the marketplace of ideas.

Deregulation as an issue is still alive. It is a focal point of debate. A strong congressional vote in the face of a threatened Carter veto moves forward the FTC containment bill that may finally put a few checks on the wholly irresponsible Federal Trade Commission. Pass the sugar-frosted flakes! The trucking industry is also likely to get a bit more deregulation than it wants. Executive cries to the contrary, deregulation is good news for the kind of companies you should own.

State and local government spending recently fell as a percentage of GNP for the first time in 30 years. Pro-growth forces are even making progress in Massachusetts.

The tax revolt also survives. The capital gain rate was cut in 1978; so was the corporate income tax rate. Some good tax-reduction bills are in the congressional hopper right now. Proposition 13 action in the states is still alive.

Of course, all is not well in any nation where the evening TV news on the economy always features an interview with a politician and/or an anti-big-business piece. It's like going to the zoo solely to look at the rats and hyenas—every time. And the citizenry is tuning out.

Recent public opinion polls are confirming my 1978 thesis. They indicate that the key thing desired today is stability. People feel out of step with the political system. The populace is sobering up. That's bullish for business. Contrary to my expectations, Carter did not bridge the gap. He made it worse. It was Congress that showed more responsiveness to the public mood, not Carter.

Even just from late 1978 to late 1979 big opinion shifts showed up. Concern about caribou is fading as the desire for energy takes precedence. Since 1976 there has been a trend in opinion toward more military spending.

Rising stock market values are creating a very positive technical potential for the market. The following is not a forecast. It is merely an outline of a plausible series of events and conditions that could help push stock prices to higher levels.

• General speculative excesses are squeezed out of the market (1968-74) but not out of the economy.

• Major stocks essentially move sideways for 15 years (1964-79); earnings and dividends rise.

• Companies discover, then learn to cope with, inflation.

• Eventually, rising values push stock prices up out of their long "consolidation" phase (where value was catching up to price).

• Suddenly, virtually everyone holding stock has at least a nominal profit, not a loss.

• Attitudes about stocks change from negative to positive.

• Stock prices soar.

• One possible prime mover: the assumed soaring value of the assets a company has in place; the imprecision in ascertaining that value aids hype-jobs by brokers.

• Soaring stock prices give the economy a lift; everybody feels like a winner.

• A speculative binge (in "asset plays"?) brings the entire market to a very vulnerable overvalued level from which a whiff of deflation could precipitate a crash. About this time in the cycle you would hear trademarks being discussed as "asset plays." And statements such as: "People are our most important asset. How can you even put a price on them?"

My response would be something incisive like, "Well, uh, exactly!" while on my way to call my broker. The selling season would be upon us.

Lloyd Clucas is a lawyer who regularly writes on the US and Japanese economic situations. His investment experience dates from 1963; his investment advisory work, from 1974.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Stock Market Returns."

Show Comments (0)