Meting Out Injustice

"The characteristic error of the constructivist rationalists in this respect is that they tend to base their argument on…the fiction that all the relevant facts are known to some one mind, and that it is possible to construct from this knowledge of the particulars a desirable social order.…They seem completely unaware that this dream simply assumes away the central problem which any effort towards the understanding or shaping of the order of society raises: our incapacity to assemble as a surveyable whole all the data which enter into the social order. Yet all those who are fascinated by the beautiful plans which result from such an approach because they are 'so orderly, so visible, so easy to understand,'…forget that these plans owe their seeming clarity to the planner's disregard of all the facts he does not know."

—F.A. Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty

"The concepts of a 'just price,' a 'just remuneration,' or a 'just distribution of incomes' are of course very old; it deserves notice, however, that in the course of the efforts of two thousand years in which philosophers have speculated about the meaning of these concepts, not a single rule has been discovered which would allow us to determine what is in this sense just in a market order. Indeed, the one group of scholars which have most persistently pursued the question…were finally driven to define the just price or wage as that price or wage which would form itself on a market in the absence of fraud, violence or privilege.…

—F.A. Hayek, Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics

One sign of the lengthy distance we have travelled away from the liberal, individualist origins of the American political order is the surprising prevalence of the visualization of social discrimination as a problem of attaining the proper ratios between groups rather than of attaining justice for the individuals that compose them. Basic to the persuasive force of this view is the sorry failure to recognize that justice-to-a-group can never be more or less or other than justice to its individual members. If the component individuals have been treated fairly, then in fact the group, too, has been fairly treated. Conversely, there is no way to treat a group unfairly without being unfair to at least some of its members. The concept of "group justice" is, then, logically derivative from and hence completely determined by the degree of justice experienced by the separate members of the group.

This might seem all too obvious, but its practical implications are only rarely heeded. Consider the problem of redressing past discriminatory injustice in, say, hiring or university admissions. Thanks to the foregoing criterion, nothing is easier to see than that any prior wrongs were committed against certain individuals by other individuals. Thus the proper moral procedure here, as in torts in general, is to seek restitution for the victims from those responsible for harming them.

It would seem ludicrous to assess a penalty upon persons innocent of inflicting the original injustice and to transfer these assessments to persons who were not the victims of the original discriminatory actions. Yet this is the explicit goal of the widespread advocacy and practice of giving "preference" in jobs and admissions to members of social groups that are thought to suffer "generally" from prejudicial treatment. For here not the slightest effort is made to identify or prove specific acts of discrimination against specific persons, nor to indemnify these victims, nor to penalize the agents responsible for these unjust acts. No, if this scenario is played out, the perpetrators get off scot-free. Instead, certain of the new applicants (usually the least-favored, marginal ones) for the positions in question, themselves admittedly innocent, are singled out in expiation of a sort of original sin. They are made to pay the full cost, in terms of denied acceptance, of "redressing" (a clear malapropism) diffuse acts of past discrimination by others. (Note that these costs are not evenly distributed over the "guilty" group as a whole.) The difference between this and the early Biblical custom of transferring the sins of the tribe to a goat and sacrificing it in atonement escapes discernment.

Nor is the accuracy of the acts of restitution any better. Here certain others among the new applicants—who make no claim that they were ever harmed by the duly chosen scapegoats and who are hence in no way entitled to compensation from them—nevertheless receive it. This would surely seem a strange form of justice. The original victims have not been compensated, and the original perpetrators have paid no penalties; unoffending people are punished, and strangers are benefitted. Truly there is only madness in this method.

What ought to be even more deterring is the realization that, rather than at least staying once and for all the bad old practice of not judging individuals by a uniform and fair standard of merit, this policy commits, with an air of pious self-righteousness at that, brand new acts of this self-same sort. The target of unfairness, to be sure, has been changed, but not unfair treatment itself. It is hard to see that a policy like this that continues to make mistakes, rather than amends, is a very notable advance. For so respectable a purpose there must surely be a less-confused solution, and indeed there is: the proper course of remedy for discrimination clearly is first, to refrain from it, second, to make restitution to particular persons unfairly treated in the past, and third, to lay on condign punishment for those specific persons responsible.

This instance illustrates how substituting the group for the individual as the basic social unit in terms of which "justice" is defined can easily be alchemized in actuality into the grossest kind of injustice. As Paul Seabury writes, "When access to privilege is defined on ethnic-community lines, the basic issue of individual rights is evaded" (Commentary, Feb. 1972, p. 38).

Even if one concedes this point—that justice must be sought at the individual level, not the group level—one might still imagine that it is valid to estimate the discrimination faced by the members of a group: just look to disparities between the group's statistics and the national average for income, unemployment, and the like. Indeed, nothing is more commonplace these days than dutifully to tote up and compare such group statistics and ritually to attribute any discrepancies to the parlous state of justice. Or to lament over variations in group representation on the ascending levels of a job hierarchy. Such arguments are given a certain plausibility by the occurrence of really surprising group disparities, such as the fact that women comprise only some one percent of the tenured faculty at Berkeley.

The very simplicity of this operational approach lends a certain allure—to some irresistible—to the remedial policy it suggests, namely, to rearrange persons so as to make the group ratios come out "even." Yet the key premises presupposed by arguments of this type—that group parameters do truthfully and reliably reveal the amount of discrimination being experienced by the group's members and that no group differences would be manifest in the absence of discrimination—have rarely if ever been subjected to the critical examination they deserve. Could it be that there are processes or factors at large in society such that group ratios diverge for reasons other than discrimination? If so, all such influences must first be ruled out before any particular suspicion of prejudice arising from aberrant group concentrations can be taken seriously.

Strong reasons exist for doubting both of these assumptions. Concerning the first, it is obvious, for example, that simple group averages combine the effects of current as well as past influences. Such parameters are necessarily insensitive to the state of continuing—that is, to new occurrences of—discrimination, which is the prime target of most remedial legislation. A famous example of this is Daniel Moynihan's widely cited report that, while the income of blacks overall was only some 60 percent of that of whites, the income of young, intact Northern black families was some 93 percent of that of comparable white families. The latter statistic, of course, includes to a much smaller degree the effects of events long past, and it gives a very different picture indeed of the degree of progress being made. (This is, however, not the only cause of the difference in these figures. Also important is that the proportion of families headed by women is much higher among blacks (34 percent in 1974) than among other groups.)

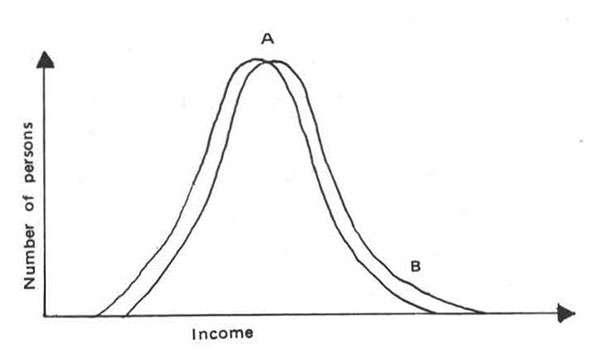

A second pitfall in making group comparisons is that what may in fact be only a minor difference in group averages will appear as a large difference at the extremes of the distributions. Consider the following hypothetical income profiles of two groups:

In the vicinity of the means (averages) of the two distributions (A), the difference in numbers of persons at each income level is hardly noticeable. But a cut at the high (or low) income extremes (as at B) would show two or three times as many members of one group at that income level as at the other. Thus the conclusion one would draw concerning the need for remedial action would be very different depending upon whether one looked at extreme or average situations. Moreover, the respective distributions need not have the same spread (variance) or shape, or be symmetrical, or even have only a single peak. (One factor that could easily generate multiple maxima would be distinct waves of immigration, for example, pre- and post-1945 East European immigration. Relative group proportions in rare positions at best (assuming profiles of the same shape) grossly exaggerate and at worst tell nothing at all about the degree of discrimination confronted by the entire group. The importance of this point lies in the fact that inferences of just this type are made whenever one cites group disparities in highly competitive, rare positions—such as the tenured faculty or the entering classes of the best universities, or the top management of large corporations, or the leading politicians—as evidence of "pervasive" or "massive" discrimination against a given group.

Yet another reason for exercising care in drawing such conclusions from local group disproportions is that, while any given selective step may itself introduce only a small difference between two groups, this effect can be greatly magnified by passage through many such "gates" acting in the same direction. For example, a modest selective differential that would convert a starting ratio of 50:50 to 55:45 in one step would, if repeated 10 times, result in a final ratio of some 80:20. Or, to view this in the reverse direction, we might easily find ourselves exercised at a group disparity of the latter size without being able to find, among the multitude of successive selections attendant upon progressing through high school, college, graduate school, and job seeking, any single locus responsible for it. And of course, before we could remedy unfair treatment, we would first have to locate it clearly.

Likewise risky is the second presumption underlying the use of group ratios as proxies for the degree of discrimination encountered by individuals—that no material factor differentially correlates with group identity, so that in the absence of discrimination no differences in group statistics should be evident. An important report appeared recently concerning discrimination against women in admission to graduate study at Berkeley in the fall of 1973. The composite figures showed approximately 20 percent fewer women accepted than would have been expected on the basis of equal probabilities of admission for the two sexes. Yet when the university departments, each of which passed independently on its own admissions, were examined one by one in an effort to identify the low culprits, only a few were found with significant sex imbalances at all. Moreover, those that had admitted an excess of men were more than balanced by those with an excess of women! How could this startling result be reconciled with the "excess" of males clearly evident in overall admissions?

It is, of course, well known that it is not equally easy to enter the 101 departments at Berkeley; the proportion of applicants admitted in 1973 ranged among departments from less than 20 percent to more than 80 percent. As it happened, the two sexes had not applied in equal ratios across this range; more of the women had applied to the more selective departments. Within such departments men and women had roughly equal, though low, chances of acceptance. When these data were combined with those from departments that had turned away a much smaller proportion of their applicants but that also had had a much smaller proportion of women among them, the result was the statistical illusion of overall bias against women. In this instance it would have been a grave error to assume that men and women were identical in all the traits pertinent to this selection, since they clearly differed in one very pertinent way, namely, their evinced preferences. Of course, this difference could itself have been conditioned by discriminatory influences elsewhere in the society (biased undergraduate counseling, pessimistic expectations of getting jobs in certain fields, etc.). But at this particular locus of selection, no additional bias was introduced, despite contrary appearances. (See Bickel, Hammel, and O'Connell, Science, Feb. 7, 1975.)

A related situation was described by Nathan Glazer when he noted that white immigrant groups such as Poles, Jews, and Italians, despite long residence here in the "melting pot" and despite having experienced much more modest discrimination than blacks, are still far from being equally spread across the country in the same jobs and residential areas as each other and as other white groups. There appears to be a degree of self-clustering preferred by the members of such ethnic collectivities even in the absence of severe strictures imposed from without. Moreover, residential segregation among blacks has been only moderately more severe than among these whites. This would suggest that no more than a modest portion of the segregation observed among urban blacks could be attributed specifically to racial discrimination. Glazer concludes, "To attempt to eliminate through public policy all concentrations of blacks and other minority groups would clearly be to attempt to undo far more than discrimination alone has created." (Affirmative Discrimination: Ethnic Inequality and Public Policy [New York: Basic, 1975], pp. 203, 153-155). We seem to have here once again, then, a case in which it would be incorrect to presume a oneness among groups in their internally generated choices.

The fallacy of wrongly presuming an identity between groups recurs in other contexts as well. Thomas Sowell notes, for instance, the great variability among groups in their age distribution (Race and Economics [New York: David McKay, 1975], p. 150). This factor, as estimated by median age, ranges from 18 (Puerto Ricans and Mexicans) to 23 (blacks) to 29 (Japanese) to 36 (Irish and Italians) to 47 (Russians). This means that parameters such as income, unemployment, and crime rates that are themselves independent functions of age must be corrected for differences in the respective age distributions of the groups being compared. Otherwise an impression of discrimination might arise even though age-matched cohorts had the same incomes, the same risks of unemployment, etc.

Another factor that can generate spurious inequalities in certain group statistics is uneven regional concentrations. Blacks still are more heavily represented in the South than elsewhere, Chicanos in the southwest, Indians on reservations, Jews in or near large cities, Basques in Nevada, and so forth. And one could well imagine that yet another factor is variations in the reliability of the figures being compared. Income figures for Chicanos, for example, might well be biased owing to illegal immigration and the consequent need for covert (and also underpaid) employment. Also, groups differ in the ease of "passing" their most "progressive" members. Groups defined by religion or nationality clearly have it easier in this regard than racial ones, and Indians more so than, say, blacks. So official statistics compiled about the residual members might well suggest in some cases a dreary, changeless picture of group progress even though social integration actually was proceeding apace.

Groups also differ markedly in the length of time the bulk of their members have been resident in this country. This matters, because the process of group acculturation and assimilation is a slow one that extends over several generations in a sort of "inter-generational relay" (Sowell, pp. 208-12). Andrew Greeley has shown, for example, that certain cultural attitudes can persist through several generations of residence here. (Ethnicity in the United States [New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1974]). Naturally, all groups are progressing steadily in acculturation, but they have, after all, commenced the journey at different times and from different starting points. There would thus be little reason to expect a mainly post-World War II immigrant group such as the Puerto Ricans to have achieved the same degree of social integration by 1976 as have the descendants of a mainly 19th-century immigrant group such as the Irish, who when they were new exhibited many of the same symptoms of social pathology now often associated with Puerto Ricans.

A group's rate of assimilation is also affected by the "capital assets" its members bring with them—whether or not they are already in command of English, their general level of education, the degree to which their originating culture values future rewards relative to immediate gratifications, the degree to which they are accustomed to urban life and the ways of democratic political power, etc. (Sowell, chap. 8). Variations in such factors can obviously cause real, although in the long run transitory, differences in "merit," for example, in productivity as judged by an employer. So even with scrupulously fair assessment of each individual's real abilities on the job, one would still observe overall group differences in income, representation in the job hierarchy, etc. The constellation of pertinent factors is evidently specific to each group: upper-class Cubans would probably already be educated, speak English, and know how to run businesses and cope in city life at the time they arrived. Hence they would be in a position from the start to integrate quickly. Rural peasants from Mexico, on the other hand, would most likely have to acquire all of these attributes after immigration in order to assimilate fully. This could easily take a generation or two for the entire group.

Yet another factor implicated in generating certain group differentials is the varying selective effects of the immigration rules themselves. The relative social and economic success of black immigrants, mainly West Indians, compared with native blacks has been remarked by Sowell (pp. 96-102) and by Glazer and Moynihan (Beyond the Melting Pot, 2d ed. [Cambridge: MIT Press, 1970], pp. 34-36. While opinions differ as to the explanation of this difference (the effects of current racism are assumed to be equal), one plausible interpretation would locate its source in the selection effected by the laws restricting entry of would-be-immigrants. These laws might be imagined to have functioned as a sort of cultural sieve allowing in only the most motivated or otherwise gifted, especially those already in possession of professional skills. It is no secret, of course, that the degree and quality of the legal stringency confronting applicants for immigration has varied greatly as a function of their national origins (and from time to time for a single group, for example, the Chinese).

Also of importance are significant average differences between some groups in manifested IQ (Jensen, Educability and Group Difference [London: Methuen, 1973]). The cause is still in dispute, but no one questions that such differences do show up on IQ tests. To the extent that the traits correlated with overt IQ (educational attainments, etc.) are differentially rewarded, this fact alone would give rise to group differences in the distribution of these rewards. Important average differences exist, too, between men and women. Eleanor Maccoby and Carol Jacklin, after a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, consider sex differences in the following traits to be "fairly well established:" verbal ability (females superior by about .25 standard deviations), visual-spatial ability (males superior by about .4 s.d.), math ability (males better, but probably by less than .4 s.d.), and aggressiveness (males substantially more aggressive) (The Psychology of Sex Differences [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1974], pp. 351-52). In addition there are those differences associated with the biological facts of motherhood and the nurture of infants and the further fact that women have available to them alternative options for social roles that are not commonly open to men. Once again, differences in group patterns would be generated by these factors alone even with no additionally prejudicial selections.

This discussion is not meant to be exhaustive, but it shows in impressive variety that the presumption of identity among social groups in all the traits that influence statistical appearances is far more likely to be wrong than right. Also, many of these nonuniformities pertain only to one or a few groups, many are hard to quantify, and most are in constant flux (personal tastes, degree of assimilation, age distribution, regional concentrations, effects of new immigration, etc.). Compounding this initial confusion is the fact that even fair societal selections can unpredictably magnify a basically small but real difference in average group "merit" into greatly aberrant group ratios in rare but highly visible positions of leadership. And too, overall group averages are slow to reflect recent advances in the fight against discrimination.

This fundamental complexity makes it impossible to project by deduction from first principles what the "ideal" social distribution of groups would be in a state of perfect justice. Recall that, given only two groups that were more or less matched in age, regional distribution, period of residence in this country, acculturation, IQ, prior education, and other "capital assets," as they passed through only a single selection step—the cited instance of graduate admissions at Berkeley—there was an unanticipated intricacy that made it impossible to foretell the proper proportions that would result in the absence of discrimination in the composite ratios. And this single unexpected fact resulted in a seeming "shortfall" of women of some 20 percent—not at all insignificant!

Only by generously positing the fundamental equality of all social groups in all important traits can any departure from statistical parity among groups be equated with discrimination against individuals. However well-meaning, the attempt to thus simplify the fight against prejudice in actuality merely posits away the very essence of the difficulty, namely, how in fact to rectify—to stop—discriminatory injustices against individuals. Such efforts clearly sacrifice accuracy for ease of analysis, and hence merely mock an approach to justice.

In the light of this impasse at the level of theoretical or "rational" calculation, several writers have directed their attention to an entirely different kind of process for combatting discrimination, namely, the operation of the market. By what arcane means do they envision that the market can reveal and also implement the "proper" group ratios? This would be an ultimate consequence of the fact that the market is constantly valuing (setting the price of) all its factors, including the worth of labor. The standard of judgment here is, of course, productivity. This is not determined by merely one person's usually imperfect opinion, but is set repetitively and competitively by all the potential consumers of this productivity in bidding for it. Discrimination means making judgments different from what would be indicated by productivity alone, and the market penalizes noneconomic decisions like this through the able force of competition. In the job market, for instance, if "there were substantial misjudgments of current group productivity, this would mean an opportunity for some employers to reap unusually high profits by concentrating on hiring members of such low-wage groups" (Sowell, p. 165). In this way, a group that has met with discrimination by one employer becomes preferentially attractive to any other employer who is merely impartial and fair. And owing to the higher profits that result, such nondiscriminatory employers will tend, other things being equal, to expand at the expense of their discriminating competitors. There is then a considerable cost to the person who indulges his taste for discrimination, a cost that will act to discourage this practice as long as he is not indifferent to his rate of return. Analogous considerations hold in the sale and rental of housing, the capital markets, consumer sales and services, and so on.

Harold Demsetz has set forth a thoughtful analysis of the ways in which the market can be used to oppose discrimination (North Carolina Law Review 43 [Feb. 1965] : 271-97). I paraphrase it as follows: (a) by offering, especially to or from a competitor, to work for a lower wage or to buy at a higher price or not to buy at all, a "non-preferred" person can force a discriminatory employer or merchant to pay a cost (at least an opportunity cost) for his prejudice; (b) members of a "non-preferred" group can concentrate their imposition of these costs upon a single merchant, thus confronting him with the threat of a major loss (for example, the bus boycotts), and indeed can deliberately select a marginally profitable firm that cannot afford to forgo any potential profits; (c) the market provides the mechanism, through the need of other employers and sellers to meet or forestall this enhanced competition, to spread such local successes beyond the situs of initial action; and (d) it is unnecessary in carrying out market operations of this kind to persuade a political majority of its justice, a slow and perhaps impossible task—one can just go ahead and do it.

These considerations argue strongly for the presumption that the particular distribution of groups observed in any given situation of interest where there exists competition and incentives for maximizing returns is in fact the best possible approximation to the "ideal" one that would obtain under the condition of fair treatment of individuals. By contrast, in situations where competition is not operative or is hindered—as in profit-regulated, legally protected monopolies or in nonprofit foundations and church organizations, or where workers or professionals can restrict competitive entry into their fields (occupational licensure, some unions), or where price bargaining has been limited (minimum-wage laws, "equal-pay-for-equal-work" rules, rent controls, legal limitations on loan interest)—the cost of all forms of discrimination has been significantly reduced or eliminated. Thus one would expect to find noneconomic considerations in personnel selection to be far more common here than in competitive situations. Sowell has adduced evidence that this is in fact the case (p. 166).

Many areas of American society are clearly highly competitive, and it is correspondingly difficult to accept allegations of large-scale discrimination in these arenas. Probably no field is more competitive than research in fundamental science at universities, especially in physics and biology, and it strains credence to believe that the very scarce resources available in those fields are frittered away on training less than the very best persons available. Yet there are wild disproportions evident among the workers in these fields if one takes gross population ratios as the standard of comparison. There are, for instance, few women or blacks, an excess of Jews and Orientals, and a serious deficit of devoutly religious persons of any persuasion.

That ratios like these, and indeed, that the ratios (whatever they are) in all departments at Berkeley, at least, are not notably influenced by discrimination is strongly supported by a thorough study carried out at HEW's behest. The study compared group ratios among the faculties of the various departments to those among new Ph.D.'s in the respective disciplines in an attempt to determine how many new persons needed to be hired to match the faculty ratios to the "availability pools," and this in order to carry out the "goals and guidelines" rather than quotas—you do perceive the difference, don't you?—mandated by HEW. This was peculiar on its face, since the current faculty were hired from past "availability pools," and there is no reason to expect the ethnic composition of the pool to be the same now as it was in the past.

The molehill result from this mountainous and tendentious effort was that no department needed to hire any Spanish-surnamed persons or American Indians to achieve parity; only one department needed to hire any blacks, and it needed only one; and only two departments needed to hire Orientals, and these needed only one each. (Johnson, New York Times Magazine, May 11, 1975, p. 18, and personal communication.) (Quietly ignored by HEW in setting its "goals and guidelines" was the perverse discovery that five departments had one or more Chicanos in excess of their "availability," six had one or more excess Asians, and seven had at least one extra black! This proves that HEW itself lacks conviction in interpreting disparities in group ratios as always due to discrimination.)

Only for women were significant "discrepancies" in the anticipated direction observed at all (31 departments "needed" to take on a total of some 90-odd women), and even this determination was rendered meaningless by the serious flaw that the "availability pools" were calculated only on the basis of total Ph.D.'s awarded nationwide in the respective disciplines and not on the basis of having ascertained how many of the women Ph.D.'s actually wanted full-time, uninterrupted jobs and were willing and able to relocate to get them. The single most important factor conditioning these wishes appears to be marriage, since Sowell has shown that unmarried women academics in fact compare rather well in professional standing with their male counterparts. "The gross 'male' versus 'female' comparisons are lopsided largely because married women drag down the averages of other women." (Public Interest, Winter 1976, p. 55.)

The empirical result of the HEW study is, then, entirely consistent with the expectation from the theory outlined above, namely, that academic competition by itself has reduced discrimination to negligible amounts. This, then, permits us to give an answer to Gertrude Ezorsky's no doubt rhetorical question: "Why does [Paul Seabury] believe that this kind of justice [that people are rewarded according to their ability and their works] looms so large in academies? Do professors have so much more integrity than ordinary mortals?" (New York Review of Books, May 16, 1974, p. 32.) The answer is: Not at all. But they do pay a cost for discriminating, even as ordinary mortals, since there is a high degree of competition in the academic contest for prestige, promotions, and grants. And thus we have excellent reason to presume that the observed social group ratios, however odd they may strike those unacquainted with the intricacies of the situation, are not to any significant degree the result of discrimination in university hiring.

It is likewise hard to imagine that the Chrysler Corporation—which in 1975 lost hundreds of millions of dollars and whose existence has recurrently been precarious—could afford the luxury of discrimination. Or small Polaroid in competition with giant Kodak. Or any computer company fighting IBM. And there can't be very many people who, in trying to realize money from selling one home in order to purchase a better one elsewhere, could afford to forgo for reasons of prejudice the highest price offered (Sowell, Race and Economics, pp. 169-71).

This analysis incidentally points up a fundamental fallacy of design in those "tests" of the prevalence of discrimination in housing that use matched pairs of black and white applicants. Since these tests are set up in such a way that landlords suffer virtually no cost for indulging their preferences for discrimination, it can not really come as a great surprise that they do. Had the comparison been set up with the two applicants differing solely in whether they came from the seller's home town, or shared the same passion for antique cars or French cooking, or had attended the same alma mater, the identical result would also have been obtained: people do exercise their eccentric personal preferences if there is zero cost to so doing. Naturally, this kind of "test" maximizes the amount of discriminatory activity detected. It also gives not the slightest indication of what we would really like to know, namely, what it would take to induce landlords to forgo their racial preferences. For some—not necessarily those most moral, but those most in need of extra income—this would surely be modest. In contrast, in a true market situation where applicants differ on a variety of factors that have to be weighed against each other (family size, job, education, "He's black but he's with a U.N. mission," etc.) and are making competitive financial offers, the actual occurrence of discrimination by race would necessarily be much less than in the contrived test situation.

None of this, of course, argues that there won't be anecdotal instances of arrant discrimination in competitive markets. There surely will be isolated instances, since the market does allow one to "purchase" this indulgence at the going "price." But one does thereby pay a price; one does not win an economic benefit (as is often and falsely alleged). And the market will minimize the social consequences—as revealed, say, in group average incomes—of even these occurrences, because the persons who there are "non-preferred" automatically become preferred by every other decision maker who is merely impartial. It is this self-correcting feature of the market, coupled with the fact that there are many competing assessors of "merit" constantly updating their evaluations, that supports the contention (no doubt surprising to some) that ensuring the conditions for the market to operate freely is the best possible way to discover the "proper" distribution of groups and simultaneously to bring it about.

To defeat discrimination, then, one does not want to try formulating an explicit, analytical solution (for example, defining "availability pools") to the problem of the "just" representation of groups and then try adjusting the groups until the indicated statistical parity is achieved. Instead, one should merely see to it that the market, whose natural tendency is toward treating individuals fairly, can function efficiently. The necessary conditions are: no force, no fraud, no state privileges, freely floating prices that permit the frequent evaluation of the worth of economic factors including labor, no imposed limits on potential return, no artificial protection against losses, open competitive entry, and the like. Having satisfactorily arranged these conditions, one then has good reason to be confident of having reduced prejudicial actions against individuals to the lowest possible level. And, having achieved this for individual persons, one will in fact have maximized fairness for the groups they may compose as well. In this splendid state of affairs, then, "how the figures add up on the basis of whatever measures of group we use may be interesting, but should be no concern of public policy" (Glazer, p. 220).

William Havender received his B.S. in horticulture from Cornell University and his Ph.D. in genetics from the University of California at Berkeley. His writings have appeared in a number of technical journals and in The Alternative.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Meting Out Injustice."

Show Comments (0)