The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

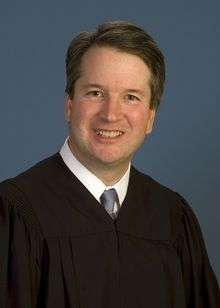

Kavanaugh on the Nixon Tapes Case

In 1999, Judge Kavanaugh suggested that the Supreme Court case that forced Nixon to turn over the Watergate tapes may have been wrongly decided. But it's not entirely clear what he now thinks about the issue.

In a 1999 roundtable discussion, Judge Brett Kavanaugh, President Trump's nominee for the Supreme Court, suggested that United States v. Nixon, the 1974 Supreme Court decision that forced Richard Nixon to turn over the Watergate tapes to prosecutors, may have been wrongly decided. This AP report summarizes what he said:

A 1999 magazine article about the roundtable was part of thousands of pages of documents that Kavanaugh has provided to the Senate Judiciary Committee as part of the confirmation process. The committee released the documents on Saturday….

"But maybe Nixon was wrongly decided — heresy though it is to say so. Nixon took away the power of the president to control information in the executive branch by holding that the courts had power and jurisdiction to order the president to disclose information in response to a subpoena sought by a subordinate executive branch official. That was a huge step with implications to this day that most people do not appreciate sufficiently… Maybe the tension of the time led to an erroneous decision," Kavanaugh said in a transcript of the discussion that was published in the January-February 1999 issue of the Washington Lawyer.

At another point in the discussion, Kavanaugh said the court might have been wise to stay out of the tapes dispute. "Should U.S. v. Nixon be overruled on the ground that the case was a nonjusticiable intrabranch dispute? Maybe so," he said.

It is not clear, however, that Kavanaugh actually believes Nixon was wrong. As the AP story also notes, he has praised the decision more recently, in a 2016 article in the Catholic University Law Review:

As a judge, you must, when appropriate, stand up to the political branches and say some action is unconstitutional or otherwise unlawful. Whether it was Marbury, or Youngstown, or Brown, or Nixon, some of the greatest moments in American judicial history have been when judges stood up to the other branches, were not cowed, and enforced the law. That takes backbone, or what some call judicial engagement. To be a good judge and a good umpire, you have to possess strong backbone.

In theory, Kavanaugh could believe that Nixon was both "an erroneous decision" and also one of "the greatest moments in American judicial history." But these two descriptions of the case are not easily reconciled. Another possibility is that, in the 1999 discussion, he was merely outlining a view that he himself did not necessarily agree with. He did say "maybe Nixon was wrongly decided" (emphasis added), not that it definitely was. Perhaps the "maybe" here is more important than it might initially seem. Finally, it's possible that Kavanaugh believed that Nixon was wrongly decided back in 1999, but had changed his mind about the subject by 2016. Based on the currently available evidence, it is not easy to figure out what Kavanaugh actually thinks about Nixon.

If the president could reject subpoenas for executive branch documents requested by prosecutors, and courts have no authority to enforce them, that would give him broad power to shield executive wrongdoing from investigation. That includes not just the president's own potentially illegal actions, but also those of subordinate officials. The issue goes far beyond the currently ongoing Mueller investigation into the Trump campaign's possible collusion with Russia, and could affect future investigations of other types of potentially illegal activities by the president and his subordinates.

Thus, if Kavanaugh really believes that Nixon was wrongly decided, that would be a troubling development, and a strike against him. It would, at the very least, reinforce concerns that he has an overly broad view of executive power.

Admittedly, Kavanaugh is far from the only serious legal commentator to have raised questions about Nixon. Many have suggested that it seems paradoxical that the president must disclose evidence at the request of a prosecutor who was, after all, one of his own subordinates. If Nixon had the power to fire special prosecutor Leon Jaworski (as he famously did with his predecessor Archibald Cox during the "Saturday Night Massacre") or order him to terminate his investigation, why didn't he have the seemingly lesser power to refuse to turn over particular documents or tapes?

The answer, I think, is that the power to fire a prosecutor or terminate an investigation does not imply immunity against federal laws governing subpoenas and the disclosure of relevant evidence to the courts. While the president can fire federal prosecutors or shut down a particular investigation, so long as he does not do so he and his subordinates are still subject to the same laws governing evidence as everyone else, subject to specific statutory exceptions for disclosure of national security secrets and the like. Nothing in the text of the Constitution exempts the president from obeying those laws (though of course Congress could create exceptions by statute).

Nor is this just a purely formalistic distinction. In at least some cases, it matters a great deal in practice. While Nixon could have fired Jaworski, he would have paid a high political price for doing so (especially after he had already taken a political beating for firing Cox). Resisting the release of specific pieces of evidence seemed like a less politically risky strategy, which is probably why Nixon chose to pursue it instead of axing Jaworski. Similarly, today, Trump so far has not tried to fire Mueller or shut down the Russia investigation - most likely because he fears the resulting political backlash. On the other hand, refusing to turn over specific pieces of potentially incriminating evidence might be more likely to fly under the radar screen of the public.

Even if Kavanaugh really does believe that Nixon was wrongly decided and would vote to reverse it if the opportunity arises, it is unlikely he could get four other justices to support that view on the current Court. But it is possible he could, over time, help build a majority for limiting Nixon's scope, perhaps by creating various exceptions to the President's duty to turn over documents in response to subpoenas. Nixon itself already indicates that such exceptions are available "to protect military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets." One can imagine broadening this to include other types of supposedly sensitive information.

Executive power is far from the only question that should be considered in assessing Kavanaugh's nomination. In my view, he is both a highly competent jurist, and has an excellent record on a number of other important issues. As with any nominee, the good should be weighed against the bad. We should also remember that a Supreme Court justice could well serve for many years, and hear cases on a variety of important issues that we may not be able to foresee today. But Kavanaugh's views on both Nixon and executive power generally are well worth investigating, and the Senate should definitely ask about these matters during his confirmation hearings.

Show Comments (32)