The Birth of the Living Constitution

Should we interpret the Constitution as a living document?

What's the proper method for interpreting the U.S. Constitution? Should it be viewed according to its original meaning? Or should the document be viewed in the light of contemporary conditions? If you answered no to the second question and yes to the third, you may be a living constitutionalist.

As Georgetown law professor Larry Solum explains in a fascinating new article at his Legal Theory Blog, "living constitutionalism is the view that the legal content of constitutional doctrine does and should change in response to changing circumstances and values." This view has been around for a long time. According to Solum, the phrase itself apparently dates back to a 1927 book titled The Living Constitution, though it was the influential progressive historian Charles Beard who first took the phrase and really ran with it. "Since most of the words and phrases dealing with the powers and the limits of government are vague and must in practice be interpreted by human beings," Beard wrote in 1936, "it follows that the Constitution as practice is a living thing."

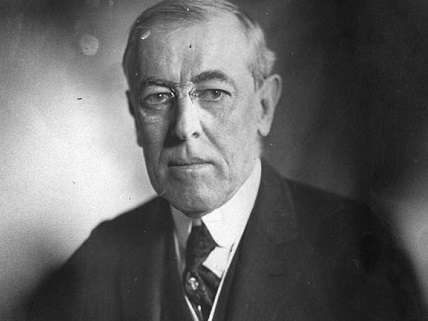

If you have any interest in U.S. legal history, Solum's article is well worth your time. But I was surprised to find that Solum made no mention of Woodrow Wilson, who must surely rank as one of the most important early theorists of living constitutionalism. For example, in his 1885 book Congressional Government, Wilson argued that the Constitution must be able to "adapt itself to the new conditions of an advancing society" or else it would be worthless to that society. "If it could not stretch itself to the measure of the times," Wilson wrote of the Constitution, it "must be thrown off and left behind, as a bygone device."

The idea of throwing off the Constitution as a bygone device proved to be extremely influential on Wilson's intellectual heirs during the New Deal period. For example, in 1935 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the National Industrial Recovery Act on the grounds that Congress's power "to regulate commerce…among the several states" did not extend so far as to allow Congress to regulate certain economic activities that never crossed any state lines whatsoever. According to the Court's 9-0 ruling in Schechter Poultry Co. v. United States, "extraordinary conditions do not create or enlarge constitutional power."

In response to that decision, President Franklin Roosevelt took a page from Woodrow Wilson and blasted the Court for adhering to the out-of-date constitutional limits originally set by the Commerce Clause. "The country was in the horse-and-buggy age when that clause was written," Roosevelt complained. As far as FDR was concerned, the justices should be using a very different method of legal interpretation, one that would "view the interstate commerce clause in the light of present-day civilization." In short: living constitutionalism.

To make a long story short, Roosevelt lost that case but his (and Wilson's) views prevailed in the long run. For better or worse, living constitutionalism is now one of the dominant methods of legal interpretation in American law.

Show Comments (120)