The Year's Best Drug Scares

Killer weed redux, pimple-faced potheads, vapin' in the boys room, Halloween high horror, and a crazy kratom crackdown

Marijuana was on the ballot in six states this year, and prohibitionists hauled out some familiar, even quaint, arguments against legalization. Three of those warnings made my list of the year's most memorable drug scares, which is rounded out by the panic over adolescent vaping and the DEA's decision to treat kratom as a public menace.

5. Killer Weed Redux

Harry Anslinger, who directed the Federal Bureau of Narcotics from 1932 to 1962, famously described marijuana as a "killer weed" that inspired irrational acts of savage violence. Anslinger's portrayal of marijuana as "the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind" helped persuade legislators unfamiliar with the plant to ban it. Now that pot prohibition is collapsing, diehard defenders of that morally and scientifically bankrupt policy are trying to revive the marijuana murder meme.

This year Roger Morgan, a leader of the campaign against marijuana legalization in California, told Reason TV that in "almost all of the mass murders that we've had in recent years," the perpetrator "has been a heavy marijuana user, because it changes the brain." The website for Morgan's organization, Stop Pot 2016, includes a list of crimes allegedly caused by marijuana—titled, apparently without irony, "Modern Reefer Madness." It mentions four mass murderers who were marijuana users, and my review of news stories from the last six years identified three more. Known cannabis consumers committed about a quarter of mass shootings in the U.S. since 2011—nobody's idea of "almost all."

Morgan's claim, then, is not remotely true, even if you ignore the distinction between correlation and causation. Nor does it seem that his Anslingeresque propaganda made much of an impression on California voters, who approved legalization by a margin of 14 points.

4. Pimple-Faced Potheads

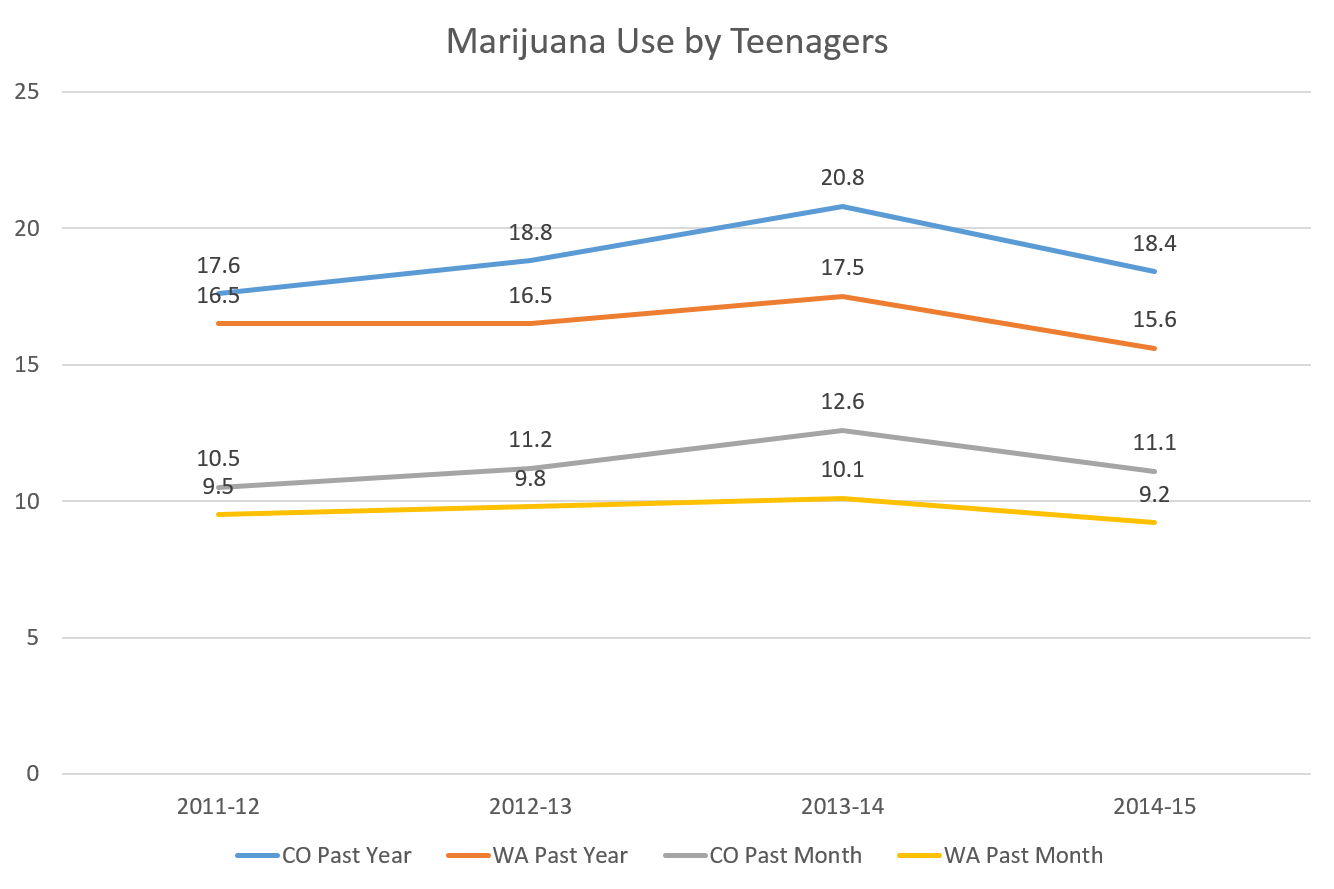

When the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicated that marijuana use by teenagers in Colorado rose after that state legalized marijuana for recreational use in 2012, drug warriors trumpeted the results, even though the change was not statistically significant. "When comparing the two-year average before and after legalization," Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), said at a hearing last April, "current marijuana use among 12-to-17-year-olds increased by 20 percent…while the national average decreased by 4 percent. In my book, that's a very big statistic, and [it] tells you a lot."

Feinstein probably won't be citing the latest numbers from that survey, which indicate that adolescent cannabis consumption became less common in Colorado during the very period when state-licensed stores began serving recreational customers. The increase in past-month adolescent marijuana use emphasized by pot prohibitionists was not statistically significant, and neither was the subsequent decline in past-month use. But NSDUH does describe last year's decline in past-year use as statistically significant, albeit "at the 0.10 level," which is twice as generous as the usual standard. Another survey with a much bigger sample of Colorado teenagers likewise found that marijuana use did not rise significantly last year.

The picture looks similar in Washington, the other state where voters approved legalization in 2012. According to NSDUH, marijuana use by teenagers rose slightly after possession was legalized for adults, then fell after marijuana stores began operating.

What about the idea that loosening state marijuana laws encourages teenagers to smoke pot by making it seem cooler, more acceptable, or less dangerous? Prohibitionists have been saying that for two decades, since California became the first state to legalize marijuana for medical use. But survey data show no such pattern, as confirmed by the latest numbers from the Monitoring the Future Study.

"I don't have an explanation," said Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which sponsors the MTF survey. "This is somewhat surprising. We had predicted, based on the changes in legalization [and] culture in the U.S. as well as decreasing perceptions among teenagers that marijuana was harmful, that [use] would go up. But it hasn't gone up."

3. Vapin' in the Boys Room

This month Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued a report that declared adolescent e-cigarette use "a major public health concern," noting with alarm that it rose "an astounding 900 percent" from 2011 to 2015. A week later, the latest results from the Monitoring the Future Study (MTF) showed that vaping by teenagers, which has been falling since the survey began asking about it in 2014, fell again this year.

Both MTF and the National Youth Tobacco Survey, the source of the "astounding" number emphasized by Murthy, show that adolescent smoking continues to fall, despite warnings from alarmists like Murthy that e-cigarettes could be a gateway to the real thing. Making that fear even less plausible, MTF finds that nonsmoking teenagers who vape typically do not vape nicotine and in any case rarely vape frequently enough to develop a nicotine habit.

These results have not dampened enthusiasm for restrictions that will hurt adult smokers in the name of saving children. "To protect our nation's young people from being harmed by these products," Murthy recommended policies, such as higher taxes, vaping bans, limits on advertising, and possibly flavor restrictions, that will undermine public health by making e-cigarettes less appealing to people who currently get their nicotine from conventional cigarettes, a much more dangerous source.

2. Halloween High Horror

For years pot prohibitionists have been warning parents that strangers with cannabis candy are determined to get their kids high by slipping marijuana edibles into their trick-or-treat bags. On Halloween this year, Bureau County, Illinois, Sheriff James Reed announced that he had come across evidence of this heretofore apocryphal threat: "suspicious looking candy marked as Crunch Choco Bar" that "has small pictures of cannabis leaves on it" and tested "positive for containing cannabis."

As a Google image search would have quickly revealed, Reed had mistaken Japanese maple leaves for cannabis leaves, which along with an inaccurate field test led him to misidentify ordinary candy as a THC-tainted treat. Read admitted his embarrassing error a couple of days later, but in the meantime local news outlets and anti-pot activists had latched onto his original alarmist claim.

"The cruel and unfortunate incident highlights the very real dangers legal marijuana has on children," said the Drug Free America Foundation. "These children were intentionally targeted by adults that were not their parents with the malicious intent of poisoning them." The organization's executive director, Calvina Fay, added:

This shows that the potential for children accidently ingesting marijuana is a real danger. It also shows that this is not just a problem for children who have parents that use marijuana and leave it unsecured and accessible around the house and it is not something we can simply blame on bad parenting. This makes it clear that children, even with the best parenting, can be exposed to marijuana. These children were unsuspecting and taken advantage of by a mean spirited person or persons with no regard for their safety or well-being.

The Halloween argument was deployed against marijuana initiatives in Nevada and Florida, without much success. More than 54 percent of Nevada voters favored legalization for recreational use, while Florida voters approved medical marijuana by a margin of more than 2 to 1.

1. Crazy Kratom Crackdown

After the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) announced an "emergency" ban on kratom at the end of August, a spokesman for the agency said "our goal is to make sure this is available."

In case that was not confusing enough, the spokesman, Melvin Patterson, also told The Washington Post that kratom, a pain-relieving leaf from Southeast Asia, does not belong in Schedule I, the most restrictive category under the Controlled Substances Act, even though that is where the DEA had just put it. He added that kratom, which the DEA says has "no currently accepted medical use," is "at a point where it needs to be recognized as medicine."

The DEA apparently was surprised by the backlash against its ban notice, which included angry calls to Capitol Hill, a demonstration near the White House, and letters from members of Congress. In October the agency withdrew the notice, saying it would delay a decision on kratom to allow time for public comments and input from the Food and Drug Administration. Patterson said criticism of the ban "was eye-opening for me personally," adding that "I want the kratom community to know that the DEA does hear them."

That attitude was quite a contrast to the deaf arrogance the DEA displayed when it announced it was temporarily placing the drug in Schedule I, a classification that lasts at least two years and could become permanent. Saying a ban was "necessary to avoid an imminent hazard to the public safety," the DEA summarily dismissed kratom's benefits while exaggerating its dangers.

Kratom, which acts as a stimulant or a sedative, depending on the dose, has been used for centuries in Southeast Asia to ease pain, boost work performance, and wean people from opiate addiction. But the DEA views all kratom use as "abuse."

Since the DEA assumed there was no legitimate reason to use kratom, it did not need to muster much evidence that the drug is intolerably dangerous. It claimed there have been "numerous deaths associated with kratom," by which it meant 30. In the whole world. Ever.

"Deaths associated with kratom" are not necessarily caused by kratom. "Kratom is considered minimally toxic," noted a 2015 literature review. "Although death has been attributed to kratom use, there is no solid evidence that kratom was the sole contributor to an individual's death."

As further proof of kratom's dangers, the DEA noted that "U.S. poison centers received 660 calls related to kratom exposure" from 2010 through 2015, an average of 110 a year. By comparison, exposures involving analgesics accounted for nearly 300,000 calls in 2014, while antidepressants and antihistamines each accounted for more than 100,000.

Show Comments (44)