Is Hillary Clinton Right That Women Have Stalled Out in the Workplace?

And that the best way to make them more employable is by adding costly "family-friendly" mandates?

In her long-awaited speech on economic policy, Hillary Clinton claimed that America is fading as a place where women can easily enter the workplace:

The movement of women into the American workforce over the past 40 years was responsible for more than $3.5 trillion in economic growth. But that progress has stalled.

The United States used to rank 7th out of 24 advanced countries in women's labor force participation. By 2013, we had dropped to 19th. That represents a lot of unused potential for our economy and for American families.

Studies show that nearly a third of this decline relative to other countries is because they're expanding family-friendly policies like paid leave and we are not.

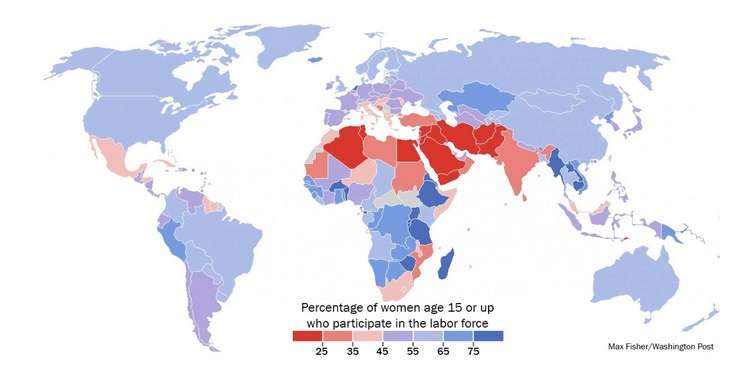

As the image at the top of this post suggests, the reality is far more complicated.

First off, the United States is doing extremely well compared to most of the world when it comes to women participating in workplace. According to government statistics, about 58 percent of American women are in the labor force (this means they are either working or looking for work). That number has generally been stable over the past several decades, varying a few percentage points. It is also about 4 percentage points higher than the average of other countries with advanced economies.

In general, the United States is ahead of many European countries which, contrary to Clinton's logic, supposedly make it more welcoming for women to work by providing free child care and whatnot. In fact, the Wash Post's Max Fisher noted in 2014, lower female labor participation rates in Europe are partly a function of government policies that attempt to increase fertility rates:

Women's rights are obviously quite good [in Europe], but many of these countries are facing demographic crises as birth rates decline. A number of European governments…are instituting all sorts of policies to encourage women to have more babies. That's a long-term economic strategy, but it also has a short-term downside, which you can see here.

There's another confounding variable as well: Global female labor-force participation rates include women aged 15 years and up. In most developed countries, women (and men) are going to high school and college when people in less-advanced economies are entering the work force. In the United States, for instance, the labor-force participation rate for women between the ages of 16-24 was just 53 percent. For women between the ages of 25 to 54, however, it was 74.5 percent, the same as it was 30 years ago. American women (and men) go to school longer than their counterparts in most of the world. And they start their careers later, too. Both of those are good things.

It's a great thing that women who want to work are able to. And the idea that Hillary Clinton will be able to boost female labor-participation rates is a guaranteed-applause getter among Democratic voters. Exactly how she will do so remains a bit of a mystery, especially since these numbers have stayed stable for a long time. In the end, "family-friendly policies" make employees more expensive and when the price of something rises, consumers (including employers) tend to purchase less of it. It's basic economics that raising the price of something is not the best way to get more of it.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), average employee total compensation—wages plus all benefits—grew from $24.95 per hour in March 2004 to $33.49 in March 2015. At the same time, total benefits (including various government mandates) grew from 28 percent of total compensation to 32 percent. Adding more and more mandatory benefits to employer costs, especially ones that will likely be used more commonly by women, is not exactly a smart way to either boost overall employment—or especially female labor participation.

Show Comments (118)