Friday A/V Club: Before Rodney King

Turning the surveillance state upside down

We live in a time of two-way surveillance. On one hand, governments and other powerful institutions can track us more closely than ever before. On the other hand, ordinary civilians can pull out a cell phone and start recording if they see a cop or some other official doing something abusive, irresponsible, or just embarrassing.

We all know that. But there was a time when hardly anyone saw such a future coming. Four decades ago, it was widely assumed that new surveillance technologies would serve only the state and the corporate world. The idea that ordinary people might point a lens back at the powerful didn't really take hold until a witness with a camcorder recorded the beating of Rodney King in 1991.

Yet that wasn't the first time a man with a camera was at the right place to tape some cops who'd gotten out of control. If you were attentive enough, you could see the outlines of the new era taking shape even before King came along. Two years earlier, for example, in Cerritos, California,

a bridal shower at the home of the Dole family, natives of Samoa, apparently attained a level of festivity that provoked the interest of the sheriff's department. In all, according to accounts in the Los Angeles Times, about 100 officers from three law enforcement agencies showed up for the event, bringing with them a helicopter whose noise and blinding searchlights reportedly added to the confusion.

The police said that they were pelted with rocks and beer bottles. Neighbors and party guests said the cops initiated the violence in which 34 persons were arrested and an undetermined number injured.

A cam-equipped neighbor decided to unobtrusively tape what he could of the scene. He got shots of an officer beating people on the ground who, it appeared, were already restrained. Dismissing the images on the tape, the sheriff said, "It would be unusual to use a baton if they were handcuffed."

Unusual or not, local newscasts gave their viewers a picture of the law in action somewhat different from the one the police would prefer to project.

The story ultimately ended with what the Los Angeles Times called "the largest civil rights damage award against police in California history." Here's a news report that includes some of the neighbor's footage, starting about 48 seconds in:

And that tape wasn't the first either. A year before police attacked the Doles' home, two men carrying cameras—Clayton Patterson and Paul Garrin—happened to be on the scene during the Tompkins Square Park Riot of 1988, when squatters and cops clashed over control of a park in Manhattan. When officers started clubbing bystanders and otherwise trampling people's rights, there was videotape to back up the victims' complaints. In one meta moment, Patterson got footage of the police smashing Garrin into the wall.

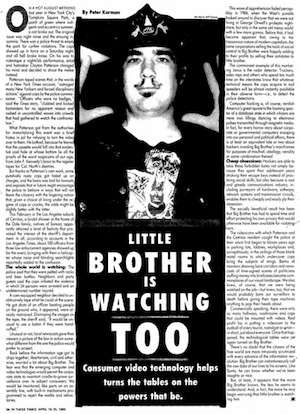

There may well be even earlier examples. But it's the events in Cerritos and in Tompkins Square Park that were cited in a prescient piece Peter Karman wrote for the leftist paper In These Times. (That's where that passage I quoted about the Dole party came from.) The article was titled "Little Brother Is Watching Too"—in those days, that headline wasn't a cliché yet—and it appeared in 1989, long before the world had heard the name Rodney King.

Citing a variety of examples—not just camcorders but radar detectors and the tools used by hackers—Karman argued that the surveillance state was being turned upside down. He also noted the central role that market forces were playing in this transformation, though he phrased this in a way calibrated to appeal to In These Times' socialist audience: "owing to the treasonous nature of modern capitalism," he wrote, "the same corporations selling the tools of social control to Big Brother were happily adding to their profits by selling their antidotes to little brother."

Later in the article, he extended the point:

The videocams with which Patterson and the Cerritos resident caught the police at their worst first began to bloom years ago in parking lots, lobbies, workplaces and, surreptitiously, in the ceilings of those blank motel rooms to which undercover cops bring the subjects of stings. Banks of monitors showing bare corridors and newscasts of time-signed scenes of politicians stuffing money into briefcases became commonplaces of our visual landscape. We also knew, of course, that we were being watched on the job—but knew, too, that we would probably bore our surveyors to death before giving their tape machines anything to pop their heads about.

Commercially speaking, there were only so many hallways, washrooms and cops that could be mounted with videos. Real profit lay in putting a videocam to the eyeball of every tourist, nostalgist or artist—in short, just about everyone. Once that happened, the technological tables again turned on Big Brother.

Today millions of Americans carry pocket-sized devices that can not just record the police but transmit their footage to the world. In the future, those tools will be even smaller and more ubiquitous. (If Google Glass–style technologies catch on with the wider public, Karman's line about "putting a videocam to the eyeball" may prove even more prophetic than it looks now.) And just about everyone understands this. What was a counterintuitive thesis in 1989 is now the conventional wisdom. It's reached the point where some anti-authoritarians have had to start issuing reminders that these technologies can still be used by powerful people too.

But there was a time when most people didn't realize that anyone but the powerful could deploy this tech. Kudos to Karman for seeing so early that the future would be more complicated than that.

(For some of Patterson's footage from the Tompkins Square Riot, go here. For some of Garrin's footage, go here. For past editions of the Friday A/V Club, go here.)

Show Comments (21)