Obamacare Gives Insurers Money To Cover Unexpected Costs. Is That a Bailout? Does It Matter?

In recent weeks, health insurers have sounded less than enthusiastic about Obamacare. At a health industry investor's conference last week, the head of Cigna warned that his company might take a loss on plans sold in Obamacare exchanges. In an SEC filing, Humana said that the demographic mix in the company's exchange plans was "more adverse" than expected. The CEO of Aetna told CNBC this week that so far, the exchange plans his company has offered in the exchanges have not successfully attracted the previously uninsured—setting up the possibility that Aetna might eventually pull out of the exchanges. And on Wednesday, credit rating agency Moody's downgraded health insurers, projecting that earnings would be less than expected in 2014 as a result of the "ongoing unstable and evolving environment" surrounding the rollout of the health law.

Insurers may be down on the law. But they're not quite ready to bail. For one thing, they've spent years reorganizing segments of their businesses around its requirements. And for another, the law provides a backstop to cushion the blow. If costs are significantly higher than insurer targets, the federal government will share the financial pain by reimbursing them for a percentage of their losses.

In other words, taxpayers will be on the hook for unexpected insurer costs—and the greater those unplanned insurer costs are, the bigger the taxpayer share of the tab will be.

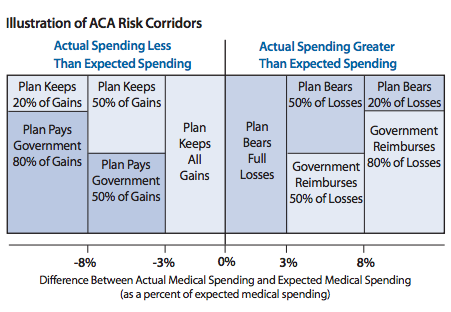

Insurers will be reimbursed for high expenses through Obamacare's risk corridors, one of several provisions in the law intended to mitigate the risk to health plans participating in the exchanges. The way that the risk corridors work is that for any insurer spending between 3 and 8 percent above an insurer's target level, the Department of Health and Human Services will reimburse them for 50 percent of the losses. For any spending that goes over the 8 percent threshold, the federal government pays 80 percent. This illustration from the American Academy of Actuaries provides a helpful way of visualizing how the program, which is active from 2014 to 2016, works:

As the graphic shows, the backstop is symmetrical. Just as insurers are covered in the case of greater than expected spending, they are also required to pay out if spending is significantly below target. But given the gloomy financial outlook for insurers offering plans on the exchanges, the widespread expectation is that the federal government will do all the paying out this year—and insurers will not pay into the system at all.

That's not what was advertised. As Wake Forest Law professor Mark Hall noted in a 2010 Health Affairs paper on Obamacare's risk provisions, the law was written under the assumption that payments to and from the government would balance out. Some insurers would spend more than expected; others would spend less. The program would be revenue neutral, or close enough.

At this point, we can be pretty sure that won't be the case. What we don't know, however, is how the government's share of insurer costs will be funded. As Hall noted, and as influential health law professor Timothy Jost also pointed out in a separate Health Affairs piece, the law makes no mention of what to do if the cost to the government is more than the amount paid in. Given that estimates suggest the payout to insurers could be worth several billion dollars this year, and that the potential costs are not capped at all, that's not a small matter.

That liability makes for a pretty big political target.

Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fl.) has already dubbed the risk corridors an insurer bailout, and proposed legislation ending the program. This sparked a debate about whether the program is or is not a bailout, with some vocal opponents of the law objecting to the description.

Their argument, broadly speaking, is that it's not really a bailout because it wasn't tacked on after the fact to cover irresponsible corporate behavior. This strikes me as a semantic quibble, especially since the provision was essentially repurposed long after it was passed—transformed from the revenue-neutral risk sharing program that was originally envisioned into a mechanism for the federal government to pay off insurers who are taking a financial hit by participating in the administration's signature law. And it's a mechanism that the administration has proposed expanding in response to the messy rollout of that law, potentially putting taxpayers on the hook for even greater costs.

Does it really matter what word is used to describe it? Call it a bailout, call it corporate welfare, call it a federal insurance company subsidy made necessary by the administration's poorly designed and implemented law—what matters is that it's a provision from an unpopular law that puts taxpayers on the hook for the health insurance industry's bottom line. No matter what you call it, it's an ugly giveaway to insurers that wasn't initially sold as such.

It's also a provision that the administration believes is necessary for the survival of the law, and the health insurance industry it regulates. In its justification for awarding a rapid no-bid contract to Accenture, the tech firm brought in to work on the federal exchange system after last year's disastrous launch, the federal government explained that it needs the financial management system that's supposed to make the risk corridor payments to be completed by mid-March of 2014. Without that system in place, the administration might end up inaccurately forecasting risk corridor payments, "potentially putting the entire health insurance industry at risk." That risk, the administration said, put the "entire healthcare reform program" in jeopardy.

Bailout or no, then, at this point the debate remains somewhat academic: The financial backend for making the risk corridor payments, a system the administration claims to believe is absolutely necessary to the law's success, hasn't even been built yet—and the administration just switched tech contractors in a panic after the last one utterly failed to deliver. That's the level of competence that's gone into implementing this law so far. Will the late-game lineup change put the system on better footing? If not, this bailout may need a bailout.

Show Comments (187)