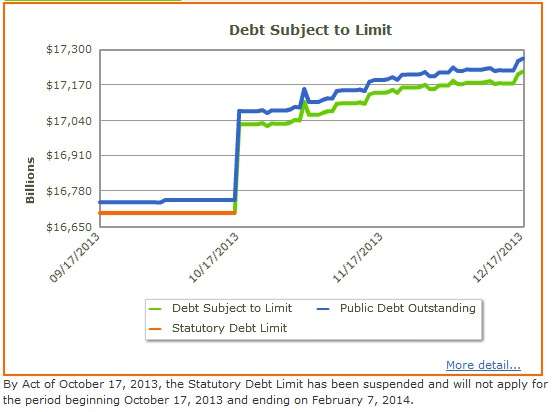

Two Months After Debt Limit Suspension, Borrowing Grows and Grows

On October 17, Congress suspended the statutory debt limit and let the U.S. government's spendthrift freak flag fly. As I wrote at the time, public debt outstanding jumped overnight by $328 billion. Woo hoo! Those credit card bonus miles are gonna be through the roof!

Since then, borrowing has slowed, but certainly not stopped (hey, we're talking about the U.S. government, here). Between October 17, 2013 and December 17, 2013, the total of public debt outstanding rose from $17.076 trillion to $17.269 trillion.

That's $17,268,587,651,056.23, if you're a big fan of commas.

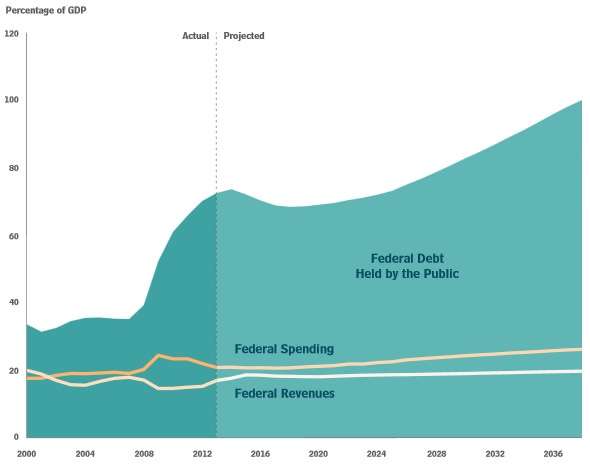

If it makes you feel any better, the Congressional Budget Office expects, in its long-term budget outlook, public debt to start dropping a bit, soon, as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product. Unfortunately, that's just before it begins a long, steady metastasis that will devour the country's economy.

The consequences of that rising debt, the CBO says, aren't pretty:

How long the nation could sustain such growth in federal debt is impossible to predict with any confidence. At some point, investors would begin to doubt the government's willingness or ability to pay U.S. debt obligations, making it more difficult or more expensive for the government to borrow money. Moreover, even before that point was reached, the high and rising amount of debt that CBO projects under the extended baseline would have significant negative consequences for both the economy and the federal budget:

- Increased borrowing by the federal government would eventually reduce private investment in productive capital, because the portion of total savings used to buy government securities would not be available to finance private investment. The result would be a smaller stock of capital and lower output and income in the long run than would otherwise be the case. Despite those reductions, however, the continued growth of productivity would make real (inflation-adjusted) output and income per person higher in the future than they are now.

- Federal spending on interest payments would rise, thus requiring larger changes in tax and spending policies to achieve any chosen targets for budget deficits and debt.

- The government would have less flexibility to use tax and spending policies to respond to unexpected challenges, such as economic downturns or wars.

- The risk of a fiscal crisis—in which investors demanded very high interest rates to finance the government's borrowing needs—would increase.

It's certainly reassuring that lawmakers are diligently hammering out a budget package that actually causes the federal government to spend more money in the future than it would absent the deal and totally ignores the very real fiscal problems that beset the leviathan in D.C.

Show Comments (30)