If Obama Cares About Unjust Drug Sentences, Why Is Weldon Angelos Still Behind Bars?

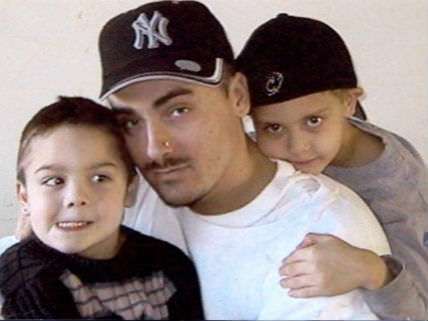

Nine years ago, Weldon Angelos, a 24-year-old rap music entrepreneur from Salt Lake City, was sentenced to 55 years in federal prison for three small-time marijuana sales. In a letter released today, 113 concerned citizens, including 60 former prosecutors, 17 former judges, seven former state attorneys general, and four former governors, remind President Obama that he has the power to free Angelos, whose case is frequently cited to illustrate the injustices resulting from mandatory minimum sentences.

U.S. District Judge Paul Cassell, who imposed what may well amount to a life sentence on Angelos, called it "unjust, cruel, and even irrational" but noted that his hands were tied by the mandatory minimums Congress had prescribed for people who engage in drug trafficking while possessing a gun: five years for the first offense and 25 years for each subsequent offense. Angelos, a first-time offender, had a handgun concealed under his clothing during two pot sales; the third count was tied to guns police found when they searched his home. He never brandished a gun, let alone fired one, and no one but Angelos and his family suffered as a result of the marijuana sales, which involved a total of a pound and a half. The letter urging Obama to commute Angelos' sentence, which was organized by the Constitution Project, highlights the perversity of the penalty he received:

Had Mr. Angelos been charged in [a Utah] court…he would have been paroled years ago. Indeed, Mr. Angelos's sentence is longer than the punishment imposed on far more serious federal offenses and offenders. His term of imprisonment exceeds the federal sentence for, among others, an aircraft hijacker, a second-degree murderer, a kidnapper, and a child rapist. Incredibly, Mr. Angelos's sentence is longer than those imposed for three aircraft hijackings, three second-degree murders, three kidnappings, or three rapes. In fact, the 55-year sentence for possessing a firearm three times in connection with minor marijuana offenses is more than twice the federal sentence for a kingpin of a major drug trafficking ring in which a death results, and more than four times the sentence for a marijuana dealer who shoots an innocent person during a drug transaction.

That's right: Angelos would have been treated less severely if he had shot the police informant posing as a customer instead of selling him pot twice more. The sentence was so egregious, the letter notes, that in 2006 "a group of 145 individuals—including former U.S. Attorneys General, retired U.S. Circuit Court Judges, retired U.S. District Court judges, a former Director of the FBI, former U.S. Attorneys, and other former high-ranking U.S. Justice Department officials—submitted a brief amici curiae in support of Mr. Angelos's case."

As the letter points out, Angelos' 55-year prison term is precisely the sort of grossly disproportionate penalty that Obama decried before he was elected president. In a 2007 speech at Howard University, for example, Obama noted that George W. Bush had at one point questioned long sentences for first-time drug offenders. "I agree with George W. Bush," Obama said. "The difference is he hasn't done anything about it. When I'm President, I will. We will review these sentences to see where we can be smarter on crime and reduce the blind and counterproductive warehousing of nonviolent offenders." Has he delivered on that promise?

In 2010, to Obama's credit, he signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced (but did not eliminate) the irrational sentencing disparity between the snorted and smoked forms of cocaine. But since that law passed Congress almost unanimously, supporting it did not take much courage. Last August, four and half years into Obama's presidency, his attorney general, Eric Holder, announced a new policy under which federal prosecutors are supposed to exclude drug weights from charges against certain low-level, nonviolent offenders to avoid triggering mandatory minimums. That policy, assuming that U.S. attorneys comply with it, has the potential to shorten the prison terms of about 500, or 2 percent, of the 25,000 federal drug offenders sentenced each year.

But Obama has conspicuously failed to use his commutation power to shorten sentences that he and Holder have both called excessively long—including those imposed on crack offenders before passage of the Fair Sentencing Act, which did not apply retroactively. He has issued only one commutation and 39 pardons in nearly five years, which so far makes him the least merciful president in U.S. history (once you exclude, as seems only fair, the first president's first term and the abbreviated terms of two presidents who died shortly after they were elected).

In light of Obama's amazingly stingy clemency record, this kowtowing passage from the Constitution Project's letter is laughable (although I understand why it was included):

We recognize that the executive clemency power has been besmirched in recent years by a few tawdry cases. But we also know that you, as a former constitutional law professor and keen student of history, appreciate the vital function that clemency plays in our tripartite system of checks and balances.

The letter includes 28 footnotes, but none of them provides evidence to back up that assertion, because there is precious little. Obama still has time to provide some more, and freeing Weldon Angelos would be a good place to start.

Show Comments (29)