The Drug War Graph Is Embarrassing. So Is Believing Obama's Promises of Reform.

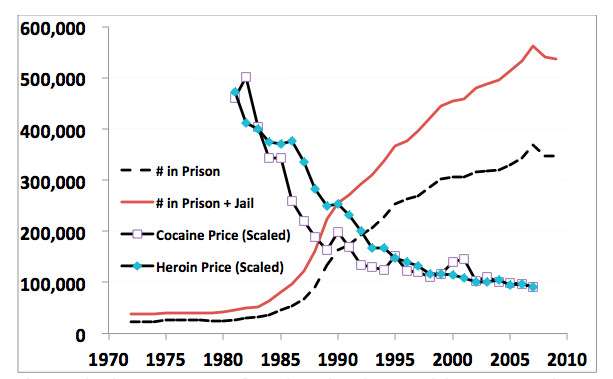

Washington Post blogger Harold Pollack presents what he calls "the most embarrassing graph in American policy," showing that the mass incaraceration of drug offenders since the early 1980s has been accompanied by declines in the retail prices of cocaine and heroin. That's embarrassing because drug law enforcement aims to reduce consumption of illegal drugs by increasing the risk and cost of supplying them, an effort that if successful should be reflected in rising retail prices. Instead we have seen just the opposite during the last few decades as the number of drug offenders behind bars has increased dramatically, peaking at 562,000 in 2007.

The ineffectiveness of supply-control measures is rooted in the economics of the black market. Illegal drugs acquire most of their value after arriving in the United States. Attempts to destroy drug crops or intercept shipments on their way to the U.S. therefore do not cost traffickers much and do not have much of an impact on retail prices. Nor does busting drug dealers in the U.S. and seizing the relatively small quantities they are apt to be holding. Both the dealers and the drugs are easily replaced. And to the extent that police succeed over the short term in raising prices by raising the risks involved in selling drugs, they also raise the returns from the business, attracting new participants and boosting the supply. A study cited by Pollack suggests how these dynamics conspire to frustrate drug warriors:

Examining a period when cocaine prices were actually plummeting, these authors estimated that a 15-fold increase in the number of incarcerated drug offenders raised street cocaine prices in the range of 5 percent to 15 percent, compared with what otherwise would have been the case. That's not much.

Joining an assortment of drug-war critics who accept at face value the current president's avowed commitment to changing course, Pollack claims "drug policy has improved during the Obama years." You know his case is weak when you see that his first reason for believing this is that "the president and his key drug policy advisers have largely abandoned the harsh war-on-drugs rhetoric of previous administrations." Obama may be allowing thousands of federal drug offenders whose sentences he admits are unjust to languish in prison, but at least he does not call the crackdown that put them there a "war." His actual policy regarding medical marijuana may be more aggressively intolerant than his predecessor's, despite promises to the contrary, but at least his rhetoric is milder. He may defend marijuana's rationally indefensible Schedule I status, but at least he claims to be doing so in the name of science.

Pollack also notes that "the number of incarcerated drug offenders has declined for the first time in decades." But according to the figures displayed in the graph, the number of drug offenders behind bars (in prisons and jails) peaked in 2007, two years before Obama took office. Furthermore, state prisons account for most incarcerated drug offenders. The number of drug offenders in federal prison increased from 95,205 in 2009 to 97,472 in 2010 before falling to 94,600 in 2011, the most recent year for which data are available. Yay?

Finally, Pollack praises Obama for expanding access to drug treatment through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Thus does Obama gain credibility as a drug policy reformer by taking a page from Richard Nixon's playbook.

Show Comments (22)