Sliding Down the Super-Cycle: Resource Doom Postponed Indefinitely

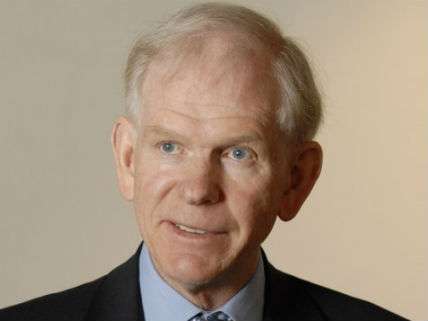

Legendary investor Jeremy Grantham admits he was wrong about "peak everything."

"Time to Wake Up: Days of Abundant Resources and Falling Prices Are Over Forever" was the title of an urgent report written by the legendary asset manager Jeremy Grantham in 2011. Grantham proclaimed the advent of a resource scarcity "paradigm shift" that was "perhaps the most important economic event since the Industrial Revolution." As evidence, he noted that "the prices of all important commodities except oil declined for 100 years until 2002, by an average of 70%." Since then, he continued, "this entire decline was erased" by the price surge, which he took as a signal that the world was using up its natural resources at an alarming rate. The result, he declared, would be a permanent shift where the prices of raw materials rise and shortages become common.

Grantham also pointed to a slowdown in crop productivity, suggesting that it would be impossible to feed the world's burgeoning population. "How we deal with this unsustainable surge in demand and not just 'peak oil,' but 'peak everything,' is going to be the greatest challenge facing our species," he wrote.

This week, Grantham took almost all of that back. Grantham, like a whole raft of professional doomsters, was declaring Peak Everything just as the latest economic super-cycle was cresting; many commodities' prices peaked the very year of his report and have been drifting downward ever since.

Economic forecasting often seems little better than reading tea leaves or parsing the convolutions of a sheep's liver. Nevertheless, some economists argue that stepping back from the crises and volatilities of the moment and taking a longer view can shed light on how the economic future will likely evolve. Specifically, they have identified what they call economic super-cycles, which trace the steady downward trend of commodity prices as they have gone through a series of decades-long peaks and valleys. A 2012 study by economists associated with the Australian National University analyzed price trends from 1650 to 2010 and concluded that "relative commodity prices present a significant and downward global trend over almost the entire capitalist age."

In their 2012 study "Super-Cycles of Commodity Prices Since the Mid-Nineteenth Century," economists Bilge Erten and José Antonio Ocampo—from Northeastern University and Columbia University, respectively—confirm that the commodity price increases in the first decade of this century were the result of a super-cycle upswing. Parsing real price data for nonfuel commodities such as food and metals from 1865 to 2009, they find evidence of four past super-cycles ranging in length from 30 to 40 years. The cycles they identify ran from 1894 to 1932, peaking in 1917; from 1932 to 1971, peaking in 1951; from 1971 to 1999, peaking in 1973; and the post-1999 episode, which is ongoing. The increases in commodity prices during these cycles are driven largely by increases in demand arising from strong periods of industrialization and urbanization, such as those experienced by Great Britain, Germany, and the United States in the 19th century, by Japan in the 20th century, and by China and other emerging economies at the beginning of the 21st century.

Erten and Ocampo find that "for non-oil commodities, the mean of each super-cycle has a tendency to be lower than that of the previous cycle." In other words, the valleys after each super-cycle peak is lower than the preceding ones—commodities become cheaper over time. In their 2012 study, they noted that metal prices were still high, but observed that "the contraction phase of this cycle has not even begun yet, which can lower the mean of the whole cycle in the upcoming years." Four years later, metal prices are nearly back to their pre-boom values. If previous commodity trends they identify are right, th

en metal prices will continue to fall and eventually will reach a new nadir lower than their previous trough.

The Dallas Federal Reserve economist Martin Stuermer tries to account for trends in commodities by looking at how prices have evolved for four minerals—copper, lead, tin, and zinc— since 1840. In a 2014 working paper, "150 Years of Boom and Bust: What Drives Mineral Commodity Prices?," he finds that commodity price increases are driven by demand shocks rather than by supply shocks. These "persistent price increases caused by commodity demand shifts trigger technological advances and new discoveries," which then lower commodity prices. A demand shock's increasing prices typically continue for 15 years or so, and the resulting supply shocks that lower prices last between five and 10 years. "Price surges caused by rapid industrialization are a recurrent phenomenon throughout history," concludes Stuermer. "Mineral commodity prices return to their declining or stable trends in the long run."

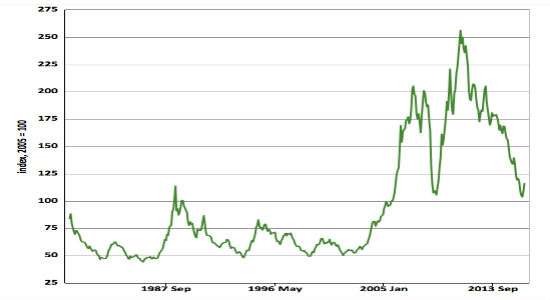

Back to Grantham. Practically ever since he issued his dire forecasts in 2011, the trend in commodity prices has been steadily downward. The Bloomberg Commodity Index (see below) has dropped 50 percent since 2011, back essentially to where it was in 1998, when it was first formulated. The index tracks commodities, including petroleum, natural gas, corn, soybeans, copper, aluminum, coffee, and live cattle. Writing this week in GMO Quarterly Letter, Grantham presented "an admission of a past mistake on resources."

First, he admits to buying into the notion of "peak oil" as petroleum prices began their steep ascendant 10 years ago. He then explains, "If we were running out of low-cost oil, I asked myself in 2011, why should we not run out of other finite resources? That everything finite runs out is known by everyone except madmen and economists (Kenneth Boulding)."

Grantham was far from alone in prophesying peak oil. For example, the Princeton geologist Kenneth Deffeyes predicted that global oil production would peak on Thanksgiving Day, 2005. As it happens, global oil production averaged 85 million barrels per day in 2005; the Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports that it was nearly 96 million barrels per day in 2015.

Astute readers will have noticed that all of the super-cycle researchers cited above make an exception for crude. For example, Erten and Ocampo find that while oil prices do indeed trace a similar boom and bust price cycle like other commodities, the average has been drifting upward since 1962. On the other hand, researchers at the Colorado School of Mines do detect super-cycles for oil after World War II: one running through 1966 to 1996, and the current one, which has just peaked. They note that the timing of the two recent crude oil super-cycles correlates with the super-cycles in metals and matches the timing of the industrialization and urbanization phases of economic development in the U.S., then Europe, and finally Asia.

The month Grantham issued his 2011 Peak Everything report saw oil prices reach $112 per barrel for refiners, just down a bit from their pre–financial crisis peak of $129 per barrel in July 2008. According to the most recent EIA figures, oil averaged $33 per barrel in March, up to $46 per barrel this week.

Interestingly, Grantham predicts in his new Quarterly Letter that oil prices will rise toward $100 per barrel by the end of this decade. But all bets are off after that, since demand for crude could falter as new technologies enable such things as transport systems based on shared electrified self-driving vehicles.

What about Grantham's food fears? Here he was worried that agricultural productivity would not be able to keep up with the world's growing population. He was particularly alarmed about allegedly impending shortages of two fertilizers, phosphorous and potash. "These two elements cannot be made, cannot be substituted, are necessary to grow all life forms, and are mined and depleted. It's a scary set of statements," he warned in a 2012 column for Nature. "What happens when these fertilizers run out is a question I can't get satisfactorily answered and, believe me, I have tried."

Grantham could not have looked very hard for satisfactory answers to worries about peak phosphorus and potash. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that current reserves of phosphate rock will last 300 years at current rates of production. The estimated total resources of phosphate rock would last over 1,300 years. Similarly, known supplies of potash would last 95 years at current rates of usage. Total world estimates of potash resources would last 7,000 years.

Grantham notes with alarm that agricultural productivity gains have slowed. Partially this is because crop breeders, agricultural scientists, and farmers rapidly ramped up yields in response to the steep food price increases of the 1970s; once food production caught up to market demand, it slowed down. In any case, agricultural productivity increases at about 1.7 percent per year; world population is increasing at 1.2 percent annually, and that rate is expected to fall. Taking into account higher future demand for meat and milk as the world grows richer, the U.S. Department of Agriculture projects a "75-percent increase in total production and consumption of major field crops between 2005 and 2050. This increase is larger than the 43-percent increase in global population projected for the same period." In the meantime, the Food and Agriculture Organization's annual deflated food price index peaked in 2011 and has dropped back to where it was in 1997.

Grantham concludes, "I do not believe that the current distress in commodities is caused by the workings of some super cycle, some decadal cosmic force, as some observers are tempted to say." Perhaps he's right. But so far, long-term bets against human ingenuity have proved to be pretty bad investment advice.

Show Comments (59)