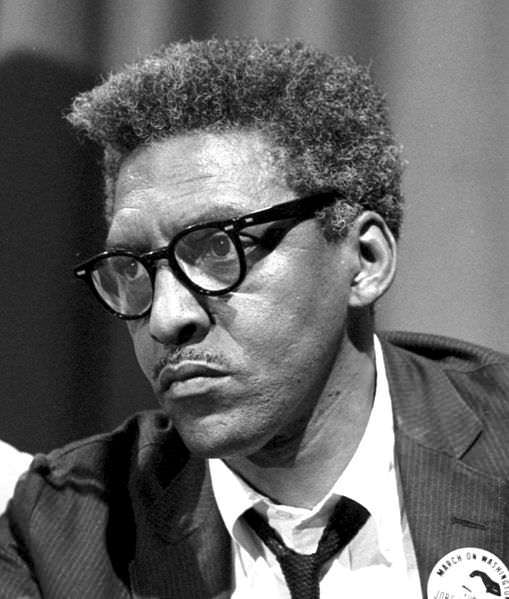

The Civil Rights Movement's Unsung Hero

For Bayard Rustin, human rights activism was never about solidarity with his own group but about freedom, justice and dignity for all

When Bayard Rustin, the often-unsung hero of the civil rights movement, died in 1987, obituaries either evaded the fact that he was openly gay or danced around it—like the New York Times, which mentioned Rustin's homosexuality but described longtime partner Walter Naegle as his "administrative assistant and adopted son." Today, such obfuscation looks both laughable and sad. By contrast, media tributes to Rustin for the recent 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King's March on Washington—in which Rustin played a key role—have often focused on his identity as a black civil rights leader who was also a gay man. Yet in an ironic twist, many of these commemorations have been just as evasive, if not outright dishonest, about another key aspect of Rustin's life: the fact that in his post-1963 career, he held many views that were anathema to the left, then and now.

The standard media narrative on Rustin is that he was sidelined in the civil rights movement and nearly erased from its history due to homophobia. But this is not entirely accurate—especially not the second part.

It's true that after a 1953 conviction on a morals charge stemming from a same-sex tryst, Rustin's compromised situation often kept him out of visible roles in the movement. Shamefully, he was forced out of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (which he had co-founded) in 1960 after black Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell tried to get leverage over King by threatening to spread rumors that he and Rustin were in a sexual relationship.

Yet, paradoxically, when Sen. Strom Thurmond openly denounced Rustin as (among other things) a homosexual a few weeks before the March on Washington, his attack ended up neutralizing the issue: other black activists rallied around him in solidarity against the segregationist politician. Scholar Arch Puddington, who later worked with Rustin at Freedom House, asserts that after this incident, Rustin's homosexuality "was never again a serious impediment to his career as civil rights or human rights advocate." He was a prominent speaker at the march; he and his mentor, union leader A. Philip Randolph, appeared on the cover of Life as its leaders. Six years later, a feature on Rustin in the New York Times Magazine stated that he "came on the intellectual and political scene as the most articulate strategist of the drive for Negro equality."

Yet the focus of the 1969 Times article—titled, "A Strategist Without a Movement"—was Rustin's marginalization and alienation from black activism, for reasons completely unrelated to his sexuality (of which the Times, of course, made no mention). Rustin was a committed liberal integrationist in an era of rising black radicalism and nationalism. Younger militants tended to see him as an Uncle Tom—particularly after a 1968 controversy in which he backed the United Federation of Teachers in a conflict with black activists in New York over the transfer of several white teachers from a mostly black school district. What's more, Rustin harshly criticized, to avoid the repetition of "against"the anti-Semitic rhetoric employed by some of the activists against the union's mostly Jewish leadership; in a speech to a conference of the B'nai B'rith Anti-Defamation League, he deplored "young Negroes speaking material directly from 'Mein Kampf.'"

The other cause of Rustin's political estrangement from the civil rights movement was his ambivalent stance on the war in Vietnam—another issue that most of the recent tributes have either ignored or fudged.

Thus, in a profile on the Buzzfeed.com website, journalist Steven Thrasher asserts that Rustin supported King in his decision to publicly condemn the war in Vietnam. Yet the truth is far more complicated. Rustin, a devout pacifist with a Quaker background and a World War II draft resister, had initially urged King to oppose the war as early as 1965, and defended his right to do so in 1967. But as historian John D'Emilio notes in the 2003 biography, Lost Prophet, Rustin himself kept his distance from antiwar activism, and "when he did make statements about the building opposition to the war, he tended toward criticism of the movement."

According to Puddington, Rustin "opposed the war but was deeply disturbed by the prospect of Vietnam's people coming under the domination of a totalitarian regime on the Soviet or Chinese model." He came to oppose American withdrawal without a negotiated settlement. He was appalled by antiwar radicals who cheered for a Viet Cong victory, and lambasted the "political naïveté" of well-meaning people who were willing to work with Communists and Maoists in the name of peace.

The tributes to Rustin often describe him as a pacifist. In fact, by 1970, his view of pacifism had changed dramatically. Rustin bluntly stated, "Whereas I used to believe that pacifism had a political value, I no longer believe that." He still considered himself a pacifist insofar as he had a strong interest in non-military means to defend freedom, which he now regarded as the most important value; without such feasible alternatives, he argued, it was "ridiculous…to talk only about peace."

Rustin further alienated the left with his passionate support for Israel. He framed the issue in stark terms: "Since Israel is a democratic state surrounded by essentially undemocratic states which have sworn her destruction, those interested in democracy everywhere must support Israel's existence." He criticized fellow civil rights leaders Andrew Young and Jesse Jackson for their contacts with the Palestine Liberation Organization, which he described as "an organization committed to racism, terrorism, and authoritarianism." In observations that remain highly relevant, he called Israel "the opiate of the Arabs" and accused "proto-fascist" Middle Eastern regimes of whipping up Israel-hatred to divert attention from their own failure to "liberate their people from poverty and misery."

Rustin's pro-Israel advocacy was part of his more general turn to international issues, including human rights activism on behalf of refugees from tyrannical regimes. He became executive chairman of Freedom House, a non-governmental organization that criticized both right-wing and left-wing dictatorships but had a strong anti-Communist bent. His views on post-colonial African politics were no less controversial than his views on the Mideast. He lamented that black majority rule usually turned out to be "a dictatorship by a small black elite over a destitute black population"; although he had campaigned for Jimmy Carter in 1976, he castigated the Carter Administration for its blindness to the dangers of Soviet expansionism in Africa. He defended the 1979 election in Zimbabwe, widely denounced as an attempt to preserve white minority power, and presciently warned that pushing for speedy radical change would result in disaster.

It's pointless to debate whether Rustin could be called a "neoconservative" in today's terms. He never wavered in his strong commitment to social democratic governance, including limited redistribution of wealth; yet it is interesting that, as Washington Post blogger Dylan Matthews points out, "neoconservative" was first made up as a term of abuse for members of the "liberal hawk" group Social Democrats USA, of which Rustin was the founding co-chairman. He was also a regular contributor to Commentary, the magazine most strongly associated with neoconservatism.

Labels aside, Bayard Rustin was a great American and a true hero. He had firsthand experience of oppression and prejudice; yet for him, human rights activism was never about solidarity with his own group but about freedom, justice and dignity for all. He had firsthand experience of the shortcomings of Western democracy—yet he understood that it was the bulwark of the values he believed in, and that it's worth fighting for. His legacy presents a challenge to both left and right: to the right, a warning against demonizing social democratic politics and gay advocacy (which Rustin embraced late in life, less as a personal cause than as an integral part of the human rights struggle); to the left, a warning against treating the West and its allies as the cause of all ills.

Show Comments (23)