10 Takeaways from the Latest CBO Budget Projections

The congressional budget scorekeeper projects the next decade of revenues and spending.

Yesterday, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)—the nonpartisan budget scorekeeper for Congress—released its updated budget projections for the next decade. This year's deficit projections are down dramatically. So is the federal budget suddenly in good shape? Far from it. In fact, debt levels are expected to remain unusually high for the foreseeable future.

But that's not all the report tells us. Here are 10 takeaways from the CBO's newest look at the future of federal spending and revenues.

1. This year's deficit will be lower than expected. The Congressional Budget Office now projects that the deficit will clock in at $642 billion this year, down from its earlier estimate of $845 billion.

2. But the downward revision in the annual deficit is mostly due to one-time changes. The revision is a product of two factors that won't be repeated in the years to follow: a $95 billion dividend payment from mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and a $105 billion revision in estimated tax collections. The CBO changed its revenue projections by just $95 billion for the entire upcoming decade—meaning that this is more of an unexpected bonus than a permanent change.

3. Projections of total annual deficits over the next decade aren't down by much. In February, the CBO projected that total deficits over the next decade would add up to $6.9 trillion. The revision puts that number at $6.3 trillion.

4. Federal debt will remain unusually high. For the next decade—and beyond—the CBO expects that federal debt levels will continue to equal more than 70 percent of the GDP, hitting a low of just less than 71 percent next year before climbing to 74 percent in 2023. As the report notes, that's a lot higher than the average of 39 percent over the past 40 years. And it's also a lot higher than it was just a few years ago: In 2007, the federal debt was just 36 percent of GDP. It won't stop rising at the end of the decade either. After 2023, debt as a percentage of the economy will "continue to be on an upward path."

5. High debt levels will have major economic consequences starting in just a few years. The nation's high and rising federal debt levels will "have serious negative consequences," the budget office says. Namely, interest payments: "When interest rates return to higher (more typical) levels, federal spending on interest payments would increase substantially."

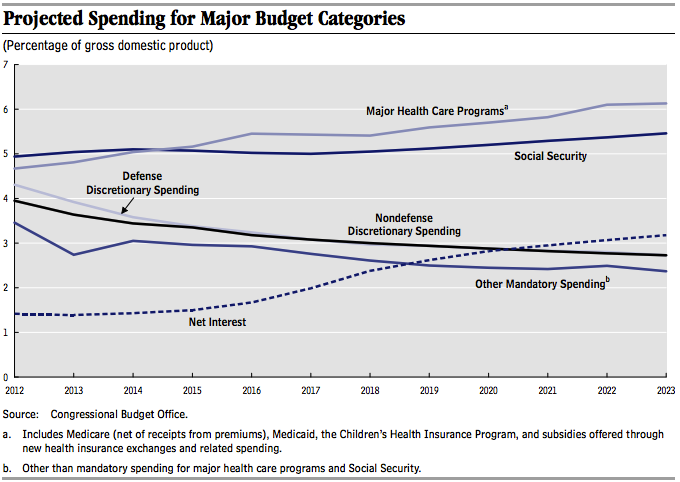

6. Interest payments will soar to near historic highs. The CBO says that higher debt levels, combined with higher expected interest rates, can be expected to "sharply boost interest payments." Assuming no changes in the law, net spending on federal interest will more than double as a percentage of the economy by 2023. In 2014, federal interest payments will equal about 1.4 percent of the economy. By 2023, the CBO projects, those payments will be about 3.2 percent—a figure that has only been exceeded once in the last 50 years.

7. More individuals will be paying higher taxes. The CBO expects that individuals will pay more relative to the size of the economy, in part because they will have higher inflation-adjusted incomes. As a result, those making more money will end up in higher tax brackets.

8. Medicaid spending will take up a greater share of the national economy, rising from 1.8 percent of GDP to 2.1 percent. The increase will be the result of both the Medicaid expansion in Obamacare and increases in how much the program spends on each individual on average.

9. Major health care programs are finally going to beat out Social Security as the top spending category. By 2015 spending on what the CBO calls "major health programs"—which include Medicare, Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program, and private health insurance subsidies offered through Medicaid—will rise above Social Security. Here's the chart:

10. This is already the rosy scenario. Under an alternative budget path, things will be noticeably worse. The CBO's headline projections are based on the assumption that Congress will keep current laws in place. But if Congress decides to override scheduled cuts to Medicare reimbursements to physicians (as it has done every year for a decade), to end the spending trims called for by sequestration (as legislators continue to call for), and to extend certain other tax carve-outs that are typically renewed, then the budget picture looks worse: total deficits will be $2.4 trillion higher, for a total of $8.8 trillion, and federal debt levels will hit 83 percent of GDP—which, as the CBO reminds us, is the highest it's been since 1948.