The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Gordon Wood on America as a "Creedal Nation" Open to all Races and Ethnicities

Wood is the leading living historian of the American Founding. He pushes back here against those who claim America should be an ethno-nationalist polity.

Gordon Wood is probably the leading living historian of the American Founding, author of such seminal works as The Creation of the American Republic and The Radicalism of the American Revolution. In a recent speech at the conservative American Enterprise Institute (reprinted in the Wall Street Journal), he pushes back against some on the right who argue that American should be an ethno-nationalist society favoring those with a particular ethnic and cultural background. This idea, he explains, goes against our Founding principles:

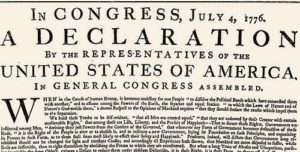

I want to say something about the Declaration of Independence and why it is so important to us Americans.

There has been some talk recently that we are not and should not be a credo nation, that beliefs in a creed are too permissive, too weak a basis for citizenship and that we need to realize that citizens who have ancestors that go back several generations have a stronger stake in the country than more recent immigrants.

This is a position that I reject as passionately as I can. We have had these blood-and soil-efforts before, in the 1890s when we also had a crisis over immigration. Some Americans tried to claim that because they had ancestors who fought in the Revolution or who came here on the Mayflower, they were more American than the recent immigrants….

The United States is not a nation like other nations, and it never has been. There is at present no American ethnicity to back up the state called the United States, and there was no such distinctive ethnicity even in 1776 when the United States was created….

Because of extensive immigration, America already had a diverse society. In addition to seven hundred thousand people of African descent and tens of thousands of native Indians, nearly all the peoples of Western Europe were present in the country. In the census of 1790 only sixty percent of the white population of well over three million remained English in ancestry…

When Lincoln declared in 1858 "all honor to Jefferson," he paid homage to the Founder who he knew could explain why the United States was one nation, and why it should remain so. Half the American people, said Lincoln, had no direct blood connection to the revolutionaries of 1776. These German, Irish, French, and Scandinavian citizens either had come from Europe themselves or their ancestors had, and they had settled in America, "finding themselves our equals in all things." Although these immigrants may have had no actual connection in blood with the revolutionary generation that could make them feel part of the rest of the nation, they had, said Lincoln, "that old Declaration of Independence" with its expression of the moral principle of equality to draw upon. This moral principle, which was "applicable to all men and all times," made all these different peoples one with the Founders, "as though they were blood of the blood and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration…." This emphasis on liberty and equality, Lincoln said, shifting images, was "the electric cord. . . that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world."

In Jefferson's Declaration Lincoln found a solution to the great problem of American identity: how the great variety of individuals in America with all their diverse ethnicities, races, and religions could be brought together into a single nation. As Lincoln grasped better than anyone ever has, the Revolution and its Declaration of Independence offered us a set of beliefs that through the generations has supplied a bond that holds together the most diverse nation that history has ever known.

Since now the whole world is in the United States, nothing but the ideals coming out of the Revolution and their subsequent rich and contentious history can turn such an assortment of different individuals into the "one people" that the Declaration says we are. To be an American is not to be someone, but to believe in something. That is why we are at heart a [creedal] nation, and that is why the 250th anniversary of the Declaration next year is so important.

Wood's emphasis on America's role as a creedal nation bound by universal liberal principles is backed by the Declaration of Independence (with its condemnation of British immigration restrictions), and by many statements by leading Founders. In his famous General Orders to the Continental Army, issued at end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, George Washington emphasized that one of the reasons the United States was founded was to create "an Asylum for the poor and oppressed of all nations and religions." He expressed similar views on other occasions, including writing to a group of newly arrived Irish immigrants that "[t]he bosom of America is open to receive not only the opulent & respectable Stranger, but the oppressed & persecuted of all Nations & Religions."

These are the principles that made America great in the first place, and returning to them is the best way to make it greater still.

I don't agree with every point Wood makes in his speech. For example, he claims that "Because assimilation is not easy, no nation should allow the percentage of foreign born to exceed about 15 percent of its population." There is no basis for this arbitrary limitation. Nations such as Australia, Canada, and Switzerland, have done well with much higher percentages of foreign-born people. In Chapter 6 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom, I describe how issues of assimilation and potential "swamping" of institutions are best addressed by "keyhole" solutions, rather than by excluding large numbers of people. Such exclusion based on morally arbitrary circumstances of ancestry and place of birth is at odds with the universalist principles of the American Founding that Gordon Wood has done so much to document and illuminate.

Wood is right to suggest that America's greater success in assimilating migrants compared to many European countries is in part due to our creedal identity and ideology. But, as noted in my book, an additional factor is open labor markets, which make it easier for immigrants to assimilate and learn the language by entering the workforce. Switzerland's relative success compared to most other European states is in part due to its similarly low level of labor restrictions.

Despite such quibbles, Wood's speech is a great summary of the principles of the Founding, and their continuing relevance today.

Show Comments (56)