The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

School's "Interest in Teaching Racial Sensitivity Is Not Sufficient" to Justify Punishing Student's "Free Expression Off-Campus"

So holds the Second Circuit: "Tying a student speaker's constitutional right to free expression solely to the reaction that speech garners from upset or angry listeners cannot be squared with [First Amendment] principles."

From Leroy v. Livingston Manor Central School District, decided today by Judge Barrington Parker joined by Judge Beth Robinson (disclosure: I argued in the case on behalf of amici Center for Individual Rights and myself):

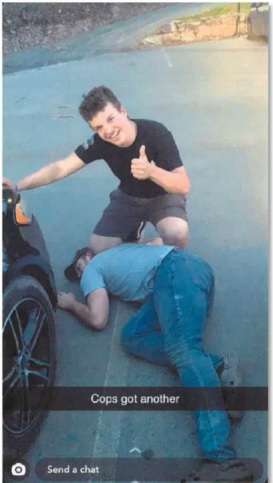

Leroy was disciplined by his school after he took a picture with his friends and posted it on social media while outside of his school campus and after school hours. He thought his post, which showed a picture of his friend kneeling on his neck with the caption "Cops got another," was a joke, but he quickly realized others viewed it as an insensitive comment on the murder of George Floyd. He removed his post after a few minutes, but not before another student took a screenshot, which she reposted on other social media platforms…. After public outcry, in-school discussions, student demonstrations and a school investigation, the school superintendent suspended Leroy and barred him from participating in various school activities for the remainder of the school year.

The court concluded that Leroy's speech was protected against discipline by the First Amendment; here's a short excerpt from the long majority opinion:

[T]he school's decision to punish Leroy was motivated, at least in part, by the fact that "the perception of those images, what it depicts, is racist in nature," and the hope that "from this experience … [Leroy] has learned some valuable lessons that will serve him better down the road." …

But as in Mahanoy Area School Dist. v. B.L. (2021), the strength of the school's interest in preventing certain kinds of speech—there, vulgarity, and here, racially insensitive speech—"is weakened considerably by the fact that [Leroy] spoke outside the school on [his] own time." Also, as in Mahanoy, Leroy "spoke under circumstances where the school did not stand in loco parentis," and "the school has presented no evidence of any general effort to [prevent such speech] outside the classroom." These facts convince us that Livingston Manor's interest in teaching racial sensitivity is not sufficient to overcome Leroy's interest in free expression off-campus.

Moreover, the District had other means at its disposal to teach these values to its students, and it utilized many of them. Teachers led classroom discussions about the posts and the issues they raised. The District held an assembly about the same issues, facilitated a student demonstration, and led discussions for interested students. These steps demonstrate that penalizing speech is not the only way schools can foster important values. Often it will not be the most effective way to do so. And, most importantly for our purposes, the other methods at the District's disposal do not restrict speech….

[T]he degree of in-school disruption [also] does not justify restricting Leroy's speech. The record reflects discussions about the posts in and out of class, leading to a fifteen-to-twenty-minute school-wide assembly and a nine-minute demonstration by several students. We believe that this level of disruption did not give the school the authority to punish off-campus, otherwise protected speech that is only indirectly related to the school environment.

Nor does the kind of disruption relied upon by the school justify regulation of Leroy's speech. The disruption at issue was not due to Leroy's speech alone, but was also driven by the independent decisionmaking of others, including fellow students, parents, and the District, in responding to Leroy's speech.

Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Comm. School Dist. (1969) [which allowed restrictions on in-class speech that caused or was likely to cause "disruption" -EV] suggests that the more relevant question is "disorder or disturbance on the part of the petitioners"—that is, disturbance on the part of the speakers themselves. Tying a student speaker's constitutional right to free expression solely to the reaction that speech garners from upset or angry listeners cannot be squared with those principles. The disturbance in school the day after Leroy's posts does not justify regulating his speech. {Suppose a student posts a highly controversial political view on social media—support for an unpopular candidate, for example—knowing that it risks upsetting some of his classmates and provoking a strong reaction. We would not hold that the speaker could be penalized for the speech because he "recklessly provoked" that response.}

Finally, … Tinker recognized that in the school context, some speech may lose constitutional protection where it involves "invasion of the rights of others." In this case, several students emailed teachers and the administration to report that Leroy's speech made them feel unsafe or uncomfortable. They reported that "posts like these can make students feel unsafe in their own school," "[a]ll POC students at LMCS are harmed and may even feel unsafe by the behavior demonstrated by these two students," "[t]he post had made me feel like it came from a place of hatred and makes me feel unsafe because at the end of the day these are people['s] lives and should not be treated as a running joke," and that they did not "feel comfortable being around classmates who happ[ily] make light of murder." …

[W]hen student speech off campus makes students feel unsafe on campus, schools may have an important parental role to play with respect to that speech. It still may not be the school's job to "guide" and "discipline" students for their off-campus actions, but it certainly falls to the school to "protect" the school community by ensuring that students feel safe at school.

We, however, are required to balance this consideration with the other two features of off-campus speech emphasized by Mahanoy Area School Dist. v. B.L. (2021). The Court noted that "the school itself has an interest in protecting a student's unpopular expression, especially when the expression takes place off campus." And "from the student speaker's perspective, regulations of off-campus speech, when coupled with regulations of on-campus speech, include all the speech a student utters during the full 24-hour day." If schools can regulate off-campus expression because it upsets other students, they are effectively authorized to prohibit students from expressing unpopular views—in or out of school.

This conundrum requires us to draw a line between speech that is deeply offensive to other students—even reasonably so—and speech that threatens their sense of security. Schools can and must protect the school community from threats—including those that are not explicit or overt enough to rise to the level of "true threats"—that make students fear for their safety…. But schools cannot—and should not—protect the school community from hearing viewpoints with which they disagree or engaging in discourse with those who have offended them….

As Mahanoy emphasized, "schools have a strong interest in ensuring that future generations understand the workings in practice of the well-known aphorism, 'I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.'" The ability to engage in civil discourse with those with whom we disagree is an essential feature of a liberal education. Teaching students that they can and should be sheltered from speech that offends them is not…. If schools can punish such speech even when it occurs off-campus, we see a real risk of deterring students from coming anywhere near controversial topics. We are called on to avoid such a chilling effect, even when doing so "shield[s] some otherwise proscribable" speech. The risk of chilling students' constitutionally protected speech counsels caution, particularly when it comes to off-campus speech….

Here, we conclude that the interest in protecting students on campus does not justify the District's response to Leroy's speech for two primary reasons. First, the record is devoid of any indication that protecting students' sense of security was the District's interest in punishing Leroy [but was based on concerns about "insensitive conduct" and "racially offensive student speech and conduct" -EV]…. Second, the record is clear that Leroy did not intend to threaten, bully, or harass any other students. It is undisputed that Leroy removed the picture from his Snapchat story within minutes, as soon as he learned how people were reacting to it….

Judge Myrna Pérez concurred in the judgment; UPDATE: I excerpt and comment on that opinion here.

Jerome T. Dorfman (Law Offices of Jerome T. Dorfman) and Adam Schulman (Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute) represent Leroy.

Show Comments (31)