The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

"The Souterian and Rehnquistian Views of Legal Talent"

From a new law review article with that name, by Andy Smarick (Manhattan Institute):

During congressional testimony in 1999, the late Justice David Souter explained that only those who graduated from one of the nation's most elite law schools would be qualified for a precious Supreme Court clerkship. He considered it risky to hire from "outside the well-trodden paths." Earlier in the same hearing, he referred to Chief Justice Rehnquist's well-known and different view: that the top performers at a wide array of law schools are "fungible." That is, the most elite schools might have more of the highest-ability students, but extraordinary talent can be found far and wide.

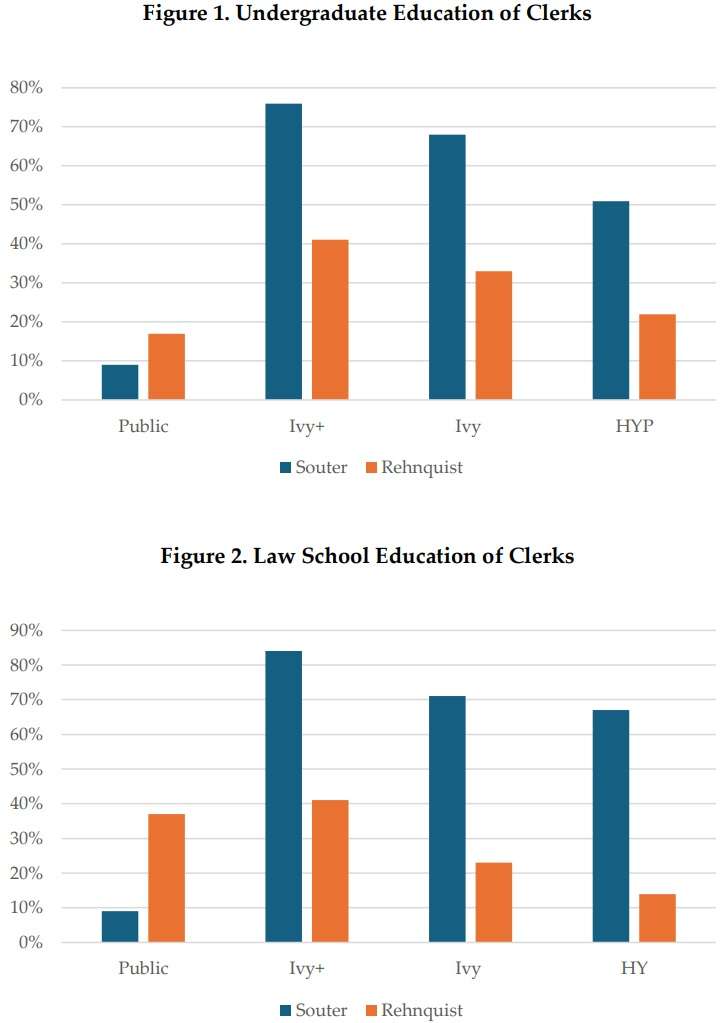

These competing visions of legal potential are reified by Justice Souter's and Chief Justice Rehnquist's actual histories of clerk hiring. Since 1980, no justice pulled from a narrower sliver of schools than Justice Souter; Chief Justice Rehnquist hired from one of the largest pools. This finding, however, is not limited to these two justices or even to justices on the United States Supreme Court. On the contrary, the legal profession appears split between the elitist Souterian vision and the egalitarian Rehnquistian vision.

The consequence is two distinct prestigious legal circles. One has graduates of a vast array of undergraduate and law schools, including flagship public schools, regional public schools, small liberal arts schools, larger selective private schools, and more. The other is dominated by graduates of a strikingly slender set of private institutions, namely Ivy and "Ivy+" schools. {My studies follow the recent convention of adding four highly selective private schools (Chicago, Duke, MIT, and Stanford) to the eight Ivies to form an "Ivy+" category.}

At least two factors seem to have created and maintained these separate circles. The first is the education of "choosers," the gatekeepers for elite professional roles. When Ivy+ graduates are in charge, they overwhelmingly hire Ivy+ graduates. They seem to hold the Souterian view that talent is concentrated in the types of schools they attended (Justice Souter graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Law School). When choosers are educated at a broader array of schools, the Rehnquistian vision predominates: individuals are hired from a broader array of schools.

The second factor is geography. In most of the nation, the top ranks of the legal profession are mostly filled by individuals from nearby public and private universities. Ivy+ graduates are few and far between. In only a few states, such as California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York, are Ivy+ degrees prevalent.

The existence of two elite legal circles—and the reasons why they both exist—matters. First, as a practical matter, it affects the opportunities (or lack thereof) available to law students and early-career lawyers. Although the top graduates of non-Ivy+ schools can rise to professional prominence in the legal community across most of America, they are at a severe disadvantage in a few locations and when Ivy+ graduates are in charge of hiring decisions. For instance, Ivy+ justices are significantly less willing to hire clerks from non-Ivy+ schools. As such, talented graduates of most of America's colleges and law schools appear to be systemically denied a fair shot. This also means that some of our legal institutions have a paucity of talented individuals from such schools.

Second, these two elite legal circles, because they have different educational profiles, may well differ in other meaningful, predictable ways. For instance, affluent, connected students have an advantage in the Ivy+ application-and-acceptance process. Those students then spend years on campuses located in a sliver of America and with cultural sensibilities different than much of America. They then disproportionately build careers in a handful of East Coast, urban settings (e.g., Boston, New York, Washington, D.C.). This is not the experience of most legal leaders.

America could, as a result, have two elite legal circles with significantly different instincts about religion and technocracy, knowledge of rural America and regional traditions, and views on politics, federalism, localism, civil society, and so on. At minimum, we should recognize the possibility, perhaps the likelihood, that these different legal circles think differently about law and policy. In what follows, I describe the differences between the "Souterian" and "Rehnquistian" views of talent, show how these differences manifest in a variety of important legal roles at the federal and state level, and describe the influence of several notable factors, including geography, ideology, and "feeder judges." …

I will close with one question and two observations. The question relates to whether and how this difference in educational profiles manifests in different professional decisions and behavior. Future research should study the extent to which these different circles reflect different politics, cultural sensibilities, and more due to their members' different academic backgrounds. It is hard to justify different segments of the legal community's top ranks having dramatically different backgrounds. But if that is the case, we should be aware of it and understand the consequences.

The first observation is that many public and non-Ivy+ private schools are producing outstanding future leaders even though those schools' graduates are all but ignored by Souterian selectors. That is, non-Ivy+ justices and selection systems in most states find talented individuals in non-Ivy+ schools to serve in important posts. The most prominent of those schools are flagship public universities. For instance, University of Mississippi School of Law currently has nine graduates on state supreme courts. Only Harvard Law and Yale Law have more graduates as state justices. But only one Mississippi Law graduate has been a Supreme Court clerk since 1980. In that same time, Harvard Law and Yale Law have had 748 clerks combined.

The law schools of Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, West Virginia, Wyoming, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arkansas educated thirty-six current state supreme court justices. But not a single Supreme Court clerk in the last forty-five years came from any of those schools. The list of undercapitalized non-flagship publics includes Arizona State, Purdue, Michigan State, Miami (Ohio), and UCLA. The list of undercapitalized private universities includes Boston College, BYU, Creighton, Denver, Drake, Marquette, Seton Hall, St. Olaf, and Willamette University.

The other observation is that the Souterian approach to talent shortchanges countless individuals. Extraordinarily able seventeen-year-olds choose to go to non-Ivy+ colleges for many reasons. Many excel at those schools as undergraduates. Many top graduates of non-Ivy+ colleges choose to go to non-Ivy+ law schools for many reasons. Many excel at those law schools. These individuals will find leadership opportunities in some places, but they will be at a severe disadvantage when Souterians are in charge. Of Justice Souter's ninety clerks only three were double-public graduates. Of Justice Kagan's sixty-one clerks, only one was a double-public school graduate.

To be a Rehnquistian does not mean discriminating against the graduates of elite private schools. Indeed, in most Rehnquistian states, Ivy+ graduates are still overrepresented in legal leadership roles. The most Rehnquistian justices—Rehnquist included—hire a significantly higher percentage of Ivy+ college and law school grads than the Ivy+ percentage of the college- and law-school-graduate population. But being a Rehnquistian does mean looking for and hiring talented individuals from a wide array of schools. It is not clear whether Souterians doubt the existence of such individuals or whether they are not interested in looking for or hiring them. Whatever the reason, it can, and should, change.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I'm sure the usual suspects are going to be enraged at this pro-DEI article.

I'm sure the usual proponents of DEI will find cause for an exception in this field.

Why would you think that?

Expanding the number of schools that feed into powerful political positions would be a great move for inclusivity on all fronts.

Yeah, agreed. In fact, a pretty easy move on the diversity front for companies that hire straight out of school is to expand the set of places that you interview from.

Not on all fronts. It won't increase the racial diversity of the hires, given that there's no reason to think that high-performing URMs are more common at lower-tier institutions.

I'm not here to talk strict rates. But more schools as feeders = more opportunities to more people of all demographics.

It's more democratic in the small-d sense. This is an opinion only but it seems to me that when it comes to higher-level clerkships we're way more credentialism-based elitist than makes sense.

Here’s the deal. People who are anti-DEI are so because DEI proponents are pretty vocal about illegal discrimination and/or discrimination on the basis of irrelevant considerations, such as race, gender, sexual orientation, etc. It’s illegal to favor people because of their race, gender, etc., and those traits tell you nothing about how well the applicant will do the job.

On the other hand, where you go to school is not a protected class, and it can tell you about the applicant. Also, the top performer at, say, George Mason Law School is likely a high performing individual, and George Mason is a good school, so picking them is going to give you a good clerk, probably just as good as someone from Harvard or Yale. By opening yourself up to a wider applicant pool, you maximize your chances of getting the best people.

Well, people who are anti-DEI are pretty stupid then, because the second half of the sentence is nonsense.

I've seen a lot of DEI schemes, and most of them are of the form of "maybe we should also hire from HBCUs and not just the Ivies" or "let's give everyone training about unconscious bias" or "let's teach CS 101 using a different programming language", not "let's only hire black women".

I recognize that there are examples of actual discriminatory DEI programs, just as there are examples of actual discriminatory hiring practices that favor groups like white men. But in my experience they're not common and have nothing to do with the way DEI is/was actually practiced in most places.

And your last sentence is the exact rationale that businesses have been using for their diversity programs: if you're intentionally or accidentally ignoring a bunch of qualified people in your hiring practices, you're missing out on a chunk of talented people so you should try to make sure that you're not making that mistake.

If that was ever how DEI worked, it has largely been taken over by people preaching oppressor–oppressed narratives and openly advocating for discriminatory hiring practices. I’ve sat through such DEI trainings, but I dared not speak up because of fear of retaliation. I really doubt I was the only one. The world is now replete with similar stories, and of circumstances of retaliation against people who did speak out. And that’s just workplaces, which are less assertive in these matters. Many universities are openly hostile towards different ideas. And of course we know that they very aggressively discriminated—and often still do—on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, etc. Indeed, most are very open and proud of doing so.

So, sorry. Whatever ideal you have about what DEI should be, it’s largely not that anymore, if it ever was. I don’t like to be nasty on this forum, but frankly, you have to have your head in the sand if you’re not seeing the purpose—often overtly so—of these “initiatives.”

Let’s put it this way: There’s nothing wrong with hiring the top graduate from, say, Howard Law School. That person is like a high-performance person. And, statistically, that’s likely to be a black person. But if, coincidentally, it’s a straight white guy, he shouldn’t be passed over for the #2 graduate because the latter is black. Modern DEI, though, would say that that’s exactly what should happen to right past wrongs, or because diversity automatically equals good, etc.

If that was ever how DEI worked, it has largely been taken over

Unsupported vibes

I’ve sat through such DEI trainings

Anecdote

The world is now replete with similar stories

Vibes

Many universities are openly hostile towards different ideas

Vibes

[W]e know that [universities] very aggressively discriminated

Very aggressively is straight up wrong - check the matriculation demographics in the past 30 years.

[universities] often still do [very aggressively discriminate]

Back to vibes

Whatever ideal you have about what DEI should be, it’s largely not that anymore

Vibes

frankly, you have to have your head in the sand if you’re not seeing the purpose

Vibes

Modern DEI, though, would say

Vibes-based fan fiction.

As usual, MAGA outrage usually focused on some random stories and not, you know, the fact that when you look at actual data it's still the same groups as it always has been overrepresented in nearly every place where we're told that white men are being horribly discriminated against.

Data > Dogma

Souter was just lazy in his hiring.

Which you can be when you are a Justice.

I don't know for sure, but I suspect the Ivy-only view is that sure, qualifying applicants could be found from other schools, but it would be more work to locate them. If the Ivies both produce enough qualified graduates to meet the need and ease the hiring process, I can well understand someone having an Ivy-only attitude. At the same time I agree that an Ivy-only attitude does a great disservice if the typical Ivy graduate is just as narrow ideologically as they are geographically.

Would it really be that much work? They could probably just hire the editors-in-chief of the law reviews at the top 36 schools and have a highly qualified clerk class.

It is the old (and now dated) quip that nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.

Chances are that the top 10-20 grads from HLS will have at least as much what I call "intellectual horsepower" as the top grad from, say U of Minn. And there is a non-trivial chance that the top grad at U of Minn was a pure grinder that got those grades more through effort and force of will than pure intellectual horsepower.

Since SCT justices (and the top Circuit Judges) are able to skim from the cream of any law school they choose, so there is little reason not to go for the top of the class from the top law school. Lower risk for at least the same return.

That is not to say that grads from "lesser" law schools might not be every bit as good or better than their competitors at the top schools, but ferreting them out is an unavoidably more difficult and risky process.

Maybe we need more "John Nash" recommendations from people qualified to give them: "XYZ is going to graduate from U Minn law in June. She is a legal genius."

Huh? Ivy League students are almost certainly more geographically diverse than any other educational institutions, given that everyone has heard of them and that they have recruiting activities across the country. Are you suggesting that Wisconsin students (for example) hale from a larger number of states and foreign countries than Harvard students?

It is so laughable to call this approach Rehnquistian that the author must either be a total idiot or hoping that by doing so he'll somehow convince conservatives to choose more from non ivy league schools, despite his own caveat that that is not what Rehnquist actually did.

It would be more accurate to say that conservative justices more often that liberal ones need to look beyond the ivys for clerks, something that already well-known and for obvious reasons.

Fuck me, Rehnquist was right about something.

FWIW one of the causes of the 2007/2008 financial collapse was Wall Street's not hiring outside a narrow academic class. IT's generally a bad strategy

For instance, University of Mississippi School of Law currently has nine graduates on state supreme courts. Only Harvard Law and Yale Law have more graduates as state justices.

The law schools of Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, West Virginia, Wyoming, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arkansas educated thirty-six current state supreme court justices.

This is a bad comparison. To become a state supreme Court Justice one has to, presumably, have lived and had a career in the state. Often, one has to active in politics as well, and graduating from the state university helps. Graduates of the prestigious schools often do not want to follow that path, so of course the state supreme courts are going to be made up mostly of in-state graduates.

That doesn't mean they are not talented individuals who could do well as SCOTUS clerks or similar jobs. But it does mean that these people are the ones the states generally have to choose from, and so there is no reason to assume there aren't some klinkers in the bunch.

Basically, as the OP says, we are talking about two populations, not just in terms of schools attended, but in terms of career goals. Saying the public/non-Ivy graduates are being neglected probably has some truth to it, but there is also the factor of what kinds of careers those graduates choose.

Agreed. The whole point of going to Yale is to get out of Montana.

Since before the Civil War it has been customary for the sons (at least) of elite American hinterlanders to get sent north and east for education, at private prep schools, at the Ivies, and at places like Johns Hopkins. John C. Calhoun went to Yale. When George W. Bush went there, he was not only a Skull and Bones legacy twice-over, he was also a Texan hop-scotching via DC and Maine, with conservative bona fides richly endowed.

Bernard11 — A Boston Area quip in support of your comment is that Boston College is the Harvard of Massachusetts.

The numbers suggest narrow-mindedness by all justices who have a hard time realizing that many people who could have gotten into elite and mostly northeastern schools do not even apply, for lots of reasons which have nothing to do with their capacity or potential. Regional bias is just one of many.

What about the mediocre students who graduate near the bottom of their law school class? Why don't they get a fair shot at a supreme court clerkship?

Would work better if you changed your handle to Roman Hruska. I don't think he would mind.

The Souter approach strikes me as misguided. You end up with a very narrow selection of people who are highly filtered. They are almost all going to represent a narrow range of views on issues.

Better to look for brilliant people all over the country. I went to Ohio State University College of Law, a top 50 school. I got an LL.M. in Taxation from the University of Florida the next year - an elite program (number 2 as ranked by US News and World Report). My UF LLM got me some interviews and a few jobs over the years, but a lot of that depended on my experience and how I presented myself during the interview process.

People like Souter are lazy snobs. It is easy to limit your search to people from one or two schools. I wonder if he took the same approach to legal research.

*The Ohio State University.

I wonder how much of this is driven by a desire, on the part of both clerks and justices, for ideological compatibility, given that most Ivy League graduates are liberals. What would the numbers look like if the survey were expanded to include top-tier institutions known to be at least somewhat more conservative-friendly (Mason and Chicago come to mind)?

First, Chicago is already included in the Ivy+ category,

Second, even the most conservative justices tend to hire from the Ivies more than anywhere else. For example, for clerks starting from 2020 to 2023, Alito hired 7 from Yale, and then 1 each from Harvard, Chicago, George Mason, Michigan and Duke.

To his credit, Thomas is one of the best on this front.

Even Thomas hires from Yale and Harvard more than everywhere else combined, though. Not to disagree with you, but to take issue with the idea that for some reason the Ivies are indoctrinating people to such an extent that the justices can't find sufficiently conservative candidates from there.

Oh yeah, that's some silly oppression-mongering.

Is that what he says is his motive? If so, I guess he should talk to Alito about it.

No, that didn't come from Thomas. Just me maybe over-reading into y81's statement that the conservative justices might be going to these other schools because the Ivies were so liberal.

But then again, if we're lumping Chicago into the pool of conservative schools and not the Ivy+ camp, then maybe y81 is onto something because in my little sample window Thomas had the most clerks from Chicago. (Which actually means I was wrong above and the Yale+Harvard combo isn't greater than everywhere else combined. It's actually Yale+Chicago.)

It's fairly obvious that having an elite drawn only from a narrow range of society is (1) bad for the republic, because those elites will be unrepresentative in ways that are unrelated to talent, and (2) good for the people doing the hiring, because it is less work for them to figure out who has sufficient talent.

Should the people doing the hiring try to do better? Yes. But should we count on them doing that? No.

That's why having multiple centers of power, with multiple sets of elites, is a good thing. Any given set of elites will probably be flawed. But the more centers of power there are, the more likely it is that those flaws will tend to cancel each other out.

Justice Robert Jackson, Albany Law School. But with a striking asterisk. Look it up.

Remarkable that this discussion—spreading afield as it has from questions about law schools and judicial clerkships—has not included mention of America's military academies as elite institutions.