The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Would Graham Linehan's "If All Else Fails, Punch Him in the Balls" Be Protected Under U.S. Law?

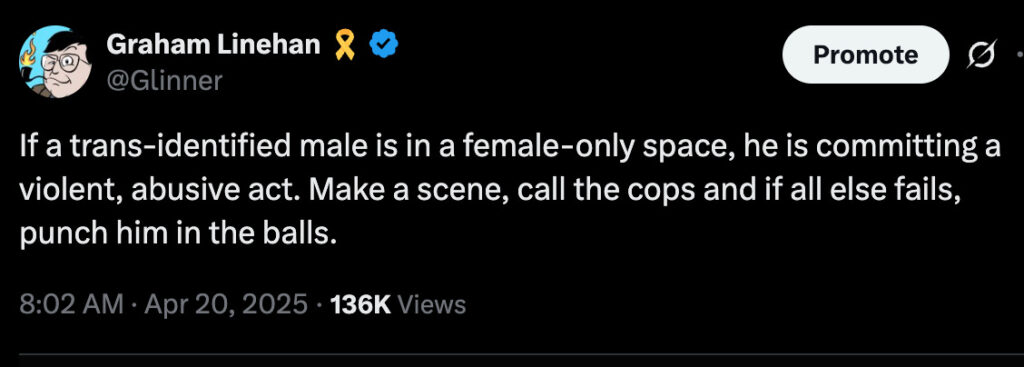

Irish writer Graham Linehan has reportedly been arrested on his return to the U.K., in part apparently based on this Tweet that he had posted:

I don't know whether this is indeed punishable under English law; I have a hard enough time keeping track of the law of one country. But someone asked me whether this would be punishable even under U.S. law, so I thought I'd post about it.

[1.] The incitement exception to the First Amendment wouldn't apply here. Consider Hess v. Indiana, a 1973 Supreme Court case, where Hess was prosecuted for saying, as a demonstration that had blocked the street was being cleared, "We'll take the fucking street later" or "We'll take the fucking street again." The Court reversed the conviction, applying (and elaborating on) the famous Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) precedent (emphasis added):

The Indiana Supreme Court placed primary reliance on the trial court's finding that Hess' statement "was intended to incite further lawless action on the part of the crowd in the vicinity of appellant and was likely to produce such action." At best, however, the statement could be taken as counsel for present moderation; at worst, it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time. This is not sufficient to permit the State to punish Hess' speech.

Under our decisions, "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action." Brandenburg. Since the uncontroverted evidence showed that Hess' statement was not directed to any person or group of persons, cannot be said that he was advocating, in the normal sense, any action. And since there was no evidence, or rational inference from the import of the language, that his words were intended to produce, and likely to produce, imminent disorder, those words could not be punished by the State on the ground that they had "a 'tendency to lead to violence.'"

The Tweet likewise appears to be "at worst, … nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time," and it wasn't "intended to produce, and likely to produce imminent disorder."

This, by the way, is why statements such as "punch a Nazi," "snitches get stitches," T-shirts with a rifle (with or without Malcolm X) and the phrase "by any means necessary," and the like are generally constitutionally protected (absent advocacy of imminent violence or, as item 2 suggests, a specific target).

[2.] U.S. law has also, since Brandenburg and Hess, recognized a solicitation exception (the leading cases are U.S. v. Williams (2008) and U.S. v. Hansen (2023)). The Court wasn't clear what the exact scope of the exception was, but it appears to apply to speech intended to produce "specific conduct," as opposed to "abstract advocacy." The solicitation exception differs from the incitement exception in that it seems to lack an imminence requirement, but applies only to such advocacy of something specific, such as a transaction as to specific contraband or, I would think, an attack on a specific person.

I think that, under that exception, a Tweet saying "You should punch trans activist Pat Jones in the balls if you ever come across him" would likely be solicitation even in the absence of imminence (at least so long as Tweet is reasonably understood as serious rather than a joke or hyperbole). But here the advocacy appears not to target any particular person.

[3.] I also don't think this would be punishable under the "true threats" exception to the First Amendment. To be an unprotected true threat, (1) the speech has to be reasonably interpretable as a statement that says the speaker (or his confederates) themselves plan to do something (as opposed to a statement that urges others to do something) and (2) the speaker must have "consciously disregarded a substantial risk that his communications would be viewed as threatening violence," see Counterman v. Colorado (2023). I don't think this is the situation here. see, e.g., U.S. v. Bagdasarian (9th Cir. 2011).

[4.] Ken White says that the Tweet is "within shouting distance of prosecutable in the U.S." ("[t]he relevant question is whether it is sufficiently imminent to meet our incitement standard") and "would very plausibly get charged in the U.S." (though "it's not clear the prosecution would succeed"). Maybe; it's hard to know for sure, since charging decisions are made by tens of thousands of prosecutors throughout the country, and different prosecutors might interpret the precedents differently (or might not even be fully aware of Hess, even if they know about the less specific but more famous Brandenburg).

But if the question is whether, under modern First Amendment precedents, the Tweet would have been constitutionally protected in U.S. courts, I think the answer is yes.

Show Comments (27)