The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Vulgar Signs Condemning City Official, ~1200 Feet from Official's Home, Constitutionally Protected

Some excerpts from today's long decision by Judge Stacey D. Neumann in Roussel v. Mayo (D. Me.):

Plaintiff Joseph F. Roussel sued the city manager of Old Town, Maine, various Old Town police officers, and the Piscataquis County Sheriff for allegedly violating his First Amendment rights. This case began as a disagreement over the masking policy at the Old Town City Hall during the COVID-19 pandemic. But it developed into an acrimonious dispute, and the situation deteriorated further when Mr. Roussel did two things that are the subject of this Order: First, while passing by the city manager's lakefront house on his friend's boat, Mr. Roussel shouted expletives at the city manager. Second, Mr. Roussel posted strongly worded and expletive-laden signs on the side of the private road leading to the city manager's house. In response, the city manager enlisted Piscataquis County Sheriff Robert Young to serve Mr. Roussel with a cease harassment notice.

The court largely allowed Roussel's First Amendment claim to go forward:

Mr. Roussel was with his friends—who lived in the area—on their boat on Schoodic Lake, in Lake View Plantation, Maine. As they happened to pass by a particular house on the lakeshore, one of Mr. Roussel's friends told him that Mr. Mayo lived there. Mr. Roussel saw two people seated on the porch near the lakeshore at Mr. Mayo's home, and he assumed that one of them was Mr. Mayo. Mr. Roussel shouted at the people on Mr. Mayo's porch, "fuck you, try trespassing me from here you tyrant piece of shit," referencing the City Hall trespass warning from the previous fall [related to the disagreement about masks].

Mr. Mayo was, in fact, sitting on his porch with a friend when Mr. Roussel passed by Mr. Mayo heard someone shouting at him but did not recognize who it was….

A week later, … Mr. Roussel drove to Lake View Plantation to meet with friends who lived there. Mr. Roussel spoke with them about posting signs on the roads nearby. After he left his friends' house, he posted … signs near Mr. Mayo's home, along Hancock Road and Railroad Bed Road. The signs displayed the following language in all capital letters:

- FUCK YOU WILLIAM MAYO

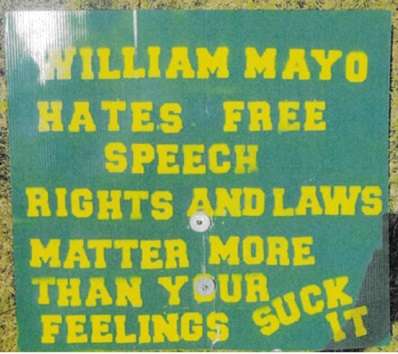

- WILLIAM MAYO HATES FREE SPEECH RIGHTS AND LAWS MATTER MORE THAN YOUR FEELINGS SUCK IT

- SOMETIMES WHEN YOUR A TYRANT AT WORK THEY FIGURE OUT WHERE YOU LIVE AND SCOTT WILCOX CANT HELP

- WILLIAM MAYO SUPPORTS BIDEN ANOTHER SHIT BAG THAT HATES FREEDOM THE CONSTITUTION MATTERS MORE THAN YOUR LIMP DICK

- FREEDOM OF SPEECH MATTERS MOST WHEN YOU DONT LIKE IT FUCK YOU WILLIAM MAYO EAT A BAG OF DICKS

The closest sign was located approximately 1,200 feet from Mr. Mayo's house, posted on a utility pole near the primary entrance into the subdivision. None of the signs were posted on the final access road to Mr. Mayo's property. Mr. Roussel himself never went closer than within 1,000 feet of Mr. Mayo's home when he posted the signs. Nor did Mr. Roussel confront—or even see—Mr. Mayo in person when he posted the signs….

The court held that Roussel's speech was constitutionally protected:

When Mr. Roussel passed by Mr. Mayo's home on the lake, he shouted at Mr. Mayo's porch, "fuck you, try trespassing me from here you tyrant piece of shit." That speech does not fall into any of the "well-defined and narrowly limited classes" of exceptions to the First Amendment's strong free speech guarantee. Although the language used is crass and derogatory, it does not constitute incitement, defamation, or obscenity. Nor is it a true threat of violence. Indeed, the Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment protects the right to shout at public officials, City of Houston, Tex. v. Hill (1987), and to use profanity, see Cohen v. California (1971) (jacket bearing the words 'Fuck the Draft' was protected speech); Hess v. Indiana (1973) (shouting "we'll take the fucking street again" while police were attempting to clear a protest was protected). Accordingly, the content of Mr. Roussel's speech on the lake is protected.

Sheriff Young argues Mr. Roussel's speech on the lake is unprotected because it was "one-to-one" speech between Mr. Roussel and Mr. Mayo. In Sheriff Young's view, speech directed from one person at another in private lacks First Amendment protection. As an initial matter, there is no such categorical exception for one-to-one speech. Sheriff Young relies exclusively on a case in which the court denied habeas relief to a petitioner convicted for violating a domestic protection order. McCurdy v. Maine (D. Me. 2020). As the court recognized in that case, the Supreme Court has not "squarely addressed the issue." See also Saxe v. State Coll. Area Sch. Dist. (3d Cir. 2001) (Alito, Circuit Judge) ("There is no categorical 'harassment exception' to the First Amendment's free speech clause.").

In any event, I need not decide the issue here as undisputed facts in the record demonstrate that Mr. Roussel did not engage in one-to-one speech. Mr. Roussel was on the boat with at least one other friend, and Mr. Mayo was on the shore with at least one other person….

As with the language shouted from the boat, albeit crude and offensive, the speech on Mr. Roussel's signs does not constitute incitement, defamation, obscenity, or any other type of speech outside the scope of First Amendment protection.

Sheriff Young briefly suggests that the sign stating, "SOMETIMES WHEN YOUR A TYRANT AT WORK THEY FIGURE OUT WHERE YOU LIVE AND SCOTT WILCOX CANT HELP" could be considered a true threat. However, Sheriff Young does not sufficiently develop this argument in his motion. He does not cite to any case law supporting his argument, explain how the signs are threatening, or demonstrate that Mr. Roussel subjectively understood the threatening nature of his speech. While both Sheriff Young and Mr. Roussel discuss Mr. Roussel's subjective intent in their depositions, Sheriff Young does not develop this testimony into a legal argument in his briefs. Therefore, because Sheriff Young does not make any reasoned argument as to whether the content of Mr. Roussel's signs constitutes an unprotected true threat, I consider that argument waived.

The court concluded that "a reasonable jury could find that Sheriff Young's decision to issue a cease harassment notice was content based":

First, Sheriff Young testified at his deposition that he explained over the phone to Mr. Roussel that he issued the cease harassment notice "because of the signs, the nature of the signs, the language that was used, the fact that he went on private property and posted it when he didn't have permission to do so." When asked whether his concerns were mostly about the language used in the signs, Sheriff Young responded, "The language was of concern, yes." Second, Sheriff Young testified that he would not have issued any order to Mr. Roussel over the language in some of the signs, but the language in others prompted him to do so. As to one sign, he testified, "I would not issue a summons just for that sign." When asked if one of the other signs would constitute disorderly conduct on Mr. Roussel's part, and thereby justify the cease harassment notice, Sheriff Young testified "I think it could be." Third, Sheriff Young testified about his interpretation of one of Mr. Roussel's signs: "Well, my sense of that … is that he was trying to convey to Mr. Mayo that he was in a place now where the chief of police in Old Town can't help him …."

Additional facts in the record, "if believed, could lead a reasonable jury to conclude" Sheriff Young issued the cease harassment order "because of disagreement with [Mr. Roussel's] message." There were other signs on the same roads, but none prompted Sheriff Young to take any action. For example, there were multiple non- political signs concerning the road's use. ECF No. 72-8 (signs reading "Caution"; "25 MPH Please Slow Down"; "Ride Right on Pavement"; "ATVs Please Slow Down or Lose the Privilege of Using this Road"; and numerous directional signs with arrows pointing to snowmobile trails, and food and lodging nearby). In Reed, the Supreme Court held that a town ordinance distinguishing between "Temporary Directional Signs," "Political Signs," and "Ideological Signs" was facially content based. That holding applies here, too. The distinction between non-political signs (like those directing traffic) and political signs (like Mr. Roussel's coarse criticism of Mr. Mayo) is content based….

And the court concluded that the restriction on Roussel's speech likely couldn't be justified under the "strict scrutiny" applicable to content-based restrictions:

Sheriff Young hints at the governmental interest in residential privacy. In his view, Mr. Roussel placed his signs on the roads close enough to Mr. Mayo's home to infringe on Mr. Mayo's privacy. Sheriff Young cites to Frisby v. Schultz (1988), in which the Supreme Court upheld a content-neutral ban on targeted residential picketing, to support his argument. There, anti-abortion protestors staged pickets directly in front of the home of a doctor who performed abortions. The Court held that picketing in front of a private residence infringes on the resident's privacy interest; therefore, the government can regulate such speech in a content-neutral manner because the captive audience "cannot avoid the objectionable speech." That such speech "inherently and offensively" intrudes on the special privacy of the home justifies regulation.

Frisby is distinguishable in two ways. First, its reasoning is limited to content- neutral regulations. As the Court explained, "[t]he ordinance also leaves open ample alternative channels of communication and is content neutral. Thus, largely because of its narrow scope, the facial challenge to the ordinance must fail." Here, by contrast, where a reasonable jury could conclude Sheriff Young's conduct was content based, Frisby's reasoning does not apply by its own terms. Second, while the parties here disagree as to the precise location of the signs on the roadside, the undisputed record demonstrates Mr. Roussel did not post any signs directly outside Mr. Mayo's home. The closest sign was approximately 1,200 feet from Mr. Mayo's house. Mr. Roussel himself never went closer than 1,000 feet to Mr. Mayo's home when he posted the signs. Nor did he confront—or even see—Mr. Mayo in person when he posted the signs. Based on these undisputed facts, the signs did not inherently intrude on Mr. Mayo's privacy in his home. Treating Frisby as permitting the government to restrict speech beyond the home's immediate surroundings would be inconsistent with its focus on picketing "narrowly directed at the household."

Additionally, while there is certainly a government interest in "protecting the well-being, tranquility, and privacy of the home," the Supreme Court has held only that it rises to a "significant government interest." That is a lower standard than the compelling interest required to justify a content-based restriction on speech. Therefore, when considering the state interest in protecting residential privacy beyond the limited context of Frisby's facts, the Supreme Court has held that content-based restrictions on protests are unconstitutional. Because a content-based speech restriction "cannot be upheld as a means of protecting residential privacy for the simple reason that nothing in the content-based … distinction has any bearing whatsoever on privacy," and a reasonable jury resolving disputed facts could find Sheriff Young issued a content-based speech restriction, summary judgment is inappropriate.

The court thus allowed the case to go forward.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Annnndddd . . . how does Prof. Volokh feel about this decision?

Appropriate?

How do you feel about it?

He feels it's a "long decision."

Sounds like they were both being jerks. But the jerk using to coercive power of government must be held to the higher standard.

"FREEDOM OF SPEECH MATTERS MOST WHEN YOU DONT LIKE IT FUCK YOU WILLIAM MAYO EAT A BAG OF DICKS"

This is a compelling argument.

That French guy thought he had won too until Furio showed up

The key takeaway here is that there's never a shortage of assholes.

"...the Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment protects the right to shout at public officials..." OK, but I wouldn't talk like that to the cop who pulls me over because of a broken tail light. Or are cops not public officials?