The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

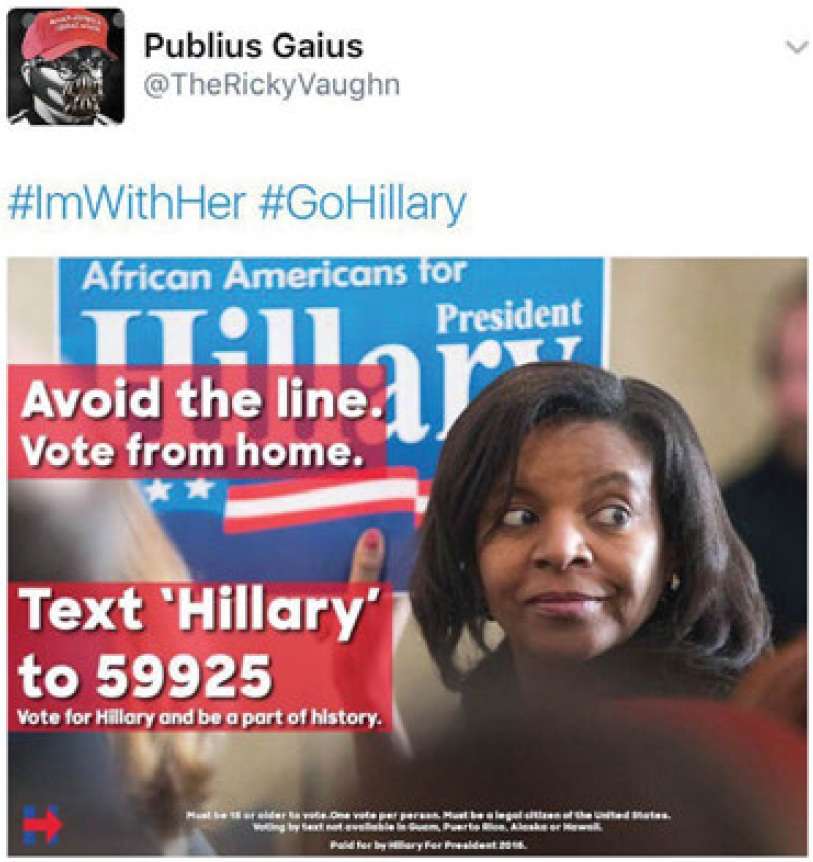

Douglass Mackey's Vote-by-Text Meme Conviction Reversed, Citing Insufficient Evidence of Conspiracy

A short excerpt from today's long decision in U.S. v. Mackey by Second Circuit Judge Debra Ann Livingston, joined by Judges Reena Raggi and Beth Robinson:

On November 1 and 2, 2016, Defendant-Appellant Douglass Mackey … posted or reposted three "memes" on Twitter falsely suggesting that supporters of then-candidate Hillary Clinton could vote in the 2016 presidential election by text message. Based on these posts, a jury … convicted him of conspiring to injure citizens in the exercise of their right to vote in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 241.Mackey argues on appeal that the evidence was insufficient to prove that he knowingly agreed to join the charged conspiracy. We agree….

The parties do not dispute either (1) that Mackey posted the memes or (2) that his doing so independently would not be a crime under Section 241. Section 241 criminalizes only conspiracies between "two or more persons." As a result, the mere fact that Mackey posted the memes, even assuming that he did so with the intent to injure other citizens in the exercise of their right to vote, is not enough, standing alone, to prove a violation of Section 241. The government was obligated to show that Mackey knowingly entered into an agreement with other people to pursue that objective.

This the government failed to do. Its primary evidence of agreement, apart from the memes themselves, consisted of exchanges among the participants in several private Twitter message groups—exchanges the government argued showed the intent of the participants to interfere with others' exercise of their right to vote. Yet the government failed to offer sufficient evidence that Mackey even viewed—let alone participated in—any of these exchanges. And in the absence of such evidence, the government's remaining circumstantial evidence cannot alone establish Mackey's knowing agreement. Accordingly, the jury's verdict and the resulting judgment of conviction must be set aside….

To begin, the government presented no evidence that Mackey participated in the conspiracy's formation. The government put forth extensive evidence that other members of the War Room, as well as members of Micro Chat and Madman #2, distributed and discussed memes suggesting citizens could vote by tweet or text in the lead-up to the election. But notably absent from this evidence was a single message from Mackey in any of these direct message groups related to the scheme. Indeed, Mackey was not even a member of Madman #2 or Micro Chat from approximately October 5, 2016 through the election. And the record contains no evidence that Mackey posted any messages in the War Room in the two weeks before he tweeted the text-to-vote memes….

The government argues that even if there is no evidence Mackey participated in the planning of the conspiracy, if he viewed the messages related to the conspiracy, he had express knowledge that an agreement had been formed. And by posting the text-to-vote memes with knowledge of this existing agreement, Mackey "knowingly joined and participated" in the conspiracy. We conclude, however, that the evidence is insufficient to establish either of these points as well.

To be sure, nothing is amiss in the government's theory as to how it proved its case. For many conspiracies—whether formed in person or online—the defendant's conduct itself, considered in light of the surrounding circumstances, is highly probative of his knowing participation in the unlawful enterprise. For example, if members of an online message group discussed the details of a plan to commit a terrorist attack, and then another member of that group who did not post any messages went on to participate in that specific attack, the defendant's actions in carrying out the attack might well be enough to support the reasonable inference that he was aware of the group's plotting and knowingly joined the conspiracy….

But the reasonableness of the inference of knowing agreement from the government's circumstantial proof depends on the nature of that proof. Consider United States v. Bufalino (2d Cir. 1960). We famously concluded there that the government had offered insufficient evidence that suspected Mafia members—who gathered in Apalachin, New York, for a prearranged meeting—agreed among themselves, in the meeting's aftermath, that they would conceal that it had been planned in advance. We emphasized the plausibility of the alternative explanation that the participants, who explained variously to law enforcement or to grand juries that they were in the area, inter alia, to visit a sick friend, attend to business, or accompany another, might well have independently decided to lie out of self-interest. We reasoned that although it was possible, as the government argued, that the "lies were told pursuant to an agreement," "[t]here [was] nothing in the record or in common experience to suggest that it [was] not just as likely that each [participant in the meeting] decided for himself that it would be wiser not to discuss all that he knew." …

Here, the conduct at issue—posting text-to-vote memes similar to others circulating publicly online— does not in isolation show awareness of, much less knowing participation in, a conspiracy. The government does not contest that Mackey downloaded the memes from 4chan but argues that the inspiration to do so came from discussion in the War Room. This is possibly true. But the inference is speculative and the government relies largely on conjecture to rule out the alternative scenario: that Mackey's conduct was independent of any knowledge of the War Room discussions. Mackey did not send any messages in the War Room in the two weeks before his text-to-vote tweets, despite having actively participated in the group in the past. Moreover, there were "over 600 messages coming in per day in the War Room" and only 12 posts related to the alleged conspiracy, two of which were sent within one minute of each other and the other 10 within a 20-minute period….

Congress expressly limited Section 241's reach to conspiracies. There are several reasons why Congress may have done so—for example, that "[c]oncerted action both increases the likelihood that the criminal object will be successfully attained and decreases the probability that the individuals involved will depart from their path of criminality," or that "[g]roup association for criminal purposes often, if not normally, makes possible the attainment of ends more complex than those which one criminal could accomplish." But the critical point is that Congress made this choice—one it has declined to deviate from in the more than 150 years since Section 241's enactment.

Here, the government conceded that Mackey downloaded his text-to-vote tweets from 4chan. It failed to establish, in accordance with its theory of the case, that Mackey became aware of the text-to-vote memes in the War Room and tweeted them pursuant to a conspiracy launched there. That theory was possible, but so was an alternative one: that Mackey became aware of the memes independently and decided on his own to post them. There was no evidence from which a juror could "choose among [the] competing inferences" as to these two scenarios and resolve those inferences in the government's favor. Nor was there any basis in "common sense and experience" to do so. And without establishing that Mackey was at least aware of the War Room posts, the additional evidence (or lack thereof) was inadequate to show his knowing participation in a conspiracy.

The court therefore had no need to discuss the broader statutory or First Amendment issues discussed in my amicus brief.

Yaakov M. Roth (with Eric S. Dreiband, Joseph P. Falvey, Caleb P. Redmond, Harry S. Graver on the brief) of Jones Day represents Mackey. Thanks again to Russell B. Balikian & Cody M. Poplin (Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP) for drafting my amicus brief (based generally on some thoughts that I'd expressed in this 2021 Tablet article).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I think it would be much cleaner to rule that this is political satire. My whole life going back 40 years, in every election I've heard some variant of a joke that one party should vote on Tuesday and the other Wednesday due to overcrowding at the polls.

The joke was that the disfavored party's votes wouldn't be counted because they voted too late. At no time, and in my mind in no universe, is that considered a serious effort to deny someone the right to vote.

This is gross over criminalization.

Agreed -

Every election has some form of false meme.

One of the most common is Vote on Tuesday for candidate A , vote on Wednesday for candidate B.

I would have voted for HRC via the text message if it didnt have one of the text message fees or put my on one of those robo call back lists. Every one knew the meme was a joke - except perhaps really stupid people.

One of the more stupid defenses of the prosecution is the claim that a larger number voted in that manner. So what - they still could vote.

The “I’d never fall for that defense” is a poor one for fraud laws.

This wasn't a fraud prosecution.

Well, it was a fraud prosecution just not a prosecution for fraud.

That meme was never fraud

it was common everyday satire

The defendant in this case wasn't charged with fraud.

Based on these posts, a jury … convicted him of conspiring to injure citizens in the exercise of their right to vote in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 241.

The term fraud for purposes of my comments is the generic use of the term, not the statutory definition.

" convicted him of conspiring to injure citizens in the exercise of their right to vote in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 241."

Yes the jury convicted him on that. The problem is the government presented zero evidence that this specific defendant conspired with anyone.

"The term fraud for purposes of my comments is the generic use of the term, not the statutory definition."

Which has no place in a discussion of an appeal of a criminal conviction.

Its a meme - a very common everyday satirical meme - that doesnt even remotely reach the level required under the statute.

The defense raised satire in a motion to dismiss, the trial judge's response was

That's an odd cite for the court to use. Alvarez held it was one's 1A right to falsely claim that he was a Medal of Honor winner. How that translates into no 1A protection for joke memes is head scratching.

I don't think it was meant that way. I quoted all 3 sentences so readers could make up their own minds, but I read it as if it had been written:

As taught by Alvarez, content-based restrictions on speech are not protected by the First Amendment if they involve a recognized traditional exception such as fraud. Whether this case involves fraud or satire is a question for the jury.

Duh. "not protected" -> "not prohibited"

But it was *HER TURN!*

The problem is that the evidence was clear that it was not intended to be satire, and was not understood as satire by many people. (Whether he conspired with others is of course another story.)

I think it is a good selection mechanism for the franchise. If a person believes that he can vote by sending a text message, and acts on that so his vote is not counted, then that is a benefit for the system as a whole to have that seriously intellectually challenged individual's choice not be part of the process.

Your standard would destroy jokes and satire. I had better not post any political memes lest the stupidest people in the population take it seriously and I be charged with a felony. It is incredibly chilling of speech. It is contrary to the Hustler magazine case.

Let me repeat: "the evidence was clear that it was not intended to be satire" (Emphasis added, this time.)

That’s the best satire, when you don’t know it’s satire

Democrats hammer conservatives when they have power.

That's why Democrats should be declare a mental illness and should be banned from having any authority over anyone else.

A prime example of the corruption of the DoJ under Biden. Politically motivated charges to suppress people's right to free speech. While this has eventually been corrected, it is very true, as Mark Steyn said, that the process is the punishment. This must have cost into the millions in legal fees. The activist judge who allowed this travesty to be tried also bears significant culpability.

Hopefully, every DoJ attorney involved in this affront to democracy has been fired by Trump.

I have no idea if he was just screwing around, or making a concerted effort to trick people out of their vote. Certainly both are among the highest values in a democracy.

I'm sure this is good for Mackey, in that his conviction gets overturned on narrow, non-controversial grounds, but it's bad for the rest of us, since we don't have a stronger statement on 1A protections.

As stated above -

That meme was never fraud

it was common everyday satire

Same as vote candidate B on wednesday - a meme that has been going around since the mid 1900's

Welcome, fraud!

Really?

Are you actually admitting that Democrat voters are that incredibly stupid?

That certainly was the Government's position.

Many voters of all parties are stupid. Some people are too functionally illiterate to know that Democratic is the adjective and Democrat the noun, for instance. And people voted for Trump, after all.

In this particular case, the evidence was that a significant number of people were tricked by the message.

Sucks to be them.

Sucks to be David Nieporent it seems!

Yep, Bigly.

I must have missed DP getting the vapors over the Donks referring to their opposition at "ReTHUGlicans" or the 'RepuliKKKan' party.

Weird

This case and the Circuit Court decision have absolutely nothing to do with fraud. The defendant wasn't charged under a fraud statute.

Also, the conviction wasn't overturned on the bases of "no reasonable person would believe this."

It was overturned because the defendant was charged under a conspiracy against rights statute and the government completely failed to offer any proof that this specific defendant conspired with anyone over anything.

fraud in the generic use of the term, not the statutory definition

Fraud in the generic lay sense is completely irrelevant to a criminal case.

it was overturned on very narrow grounds. Yet there was not " injure [injury or attempt to injure a] citizens in the exercise of their right to vote.

It was a meme - a variation of a common everyday satirical meme.

If he had been convicted of an individual conduct crime rather than participating in a conspiracy, his conviction might well have been upheld. This case had nothing to do with the underlying conduct, only with whether there was sufficient evidence he did it as part of a conspiracy rather than acting on his own.

Based on my reading of the evidence described in the Second Circuit decision, there was a much better case against the people who created the memes. They discussed how to make the memes more believable. The defendant here took the finished product.

That's the Second Circuit's decision. But it is still debatable whether the underlying conduct was protectible under the First Amendment. Not surprisingly, the Second Circuit avoided that issue.

This is a great day for free speech, even if the court did not phrase it that way.

The ruling had nothing to do with free speech. Indeed, a jury convicted him, meaning they saw more than just a jokester.

He got sprung because the federal law required a conspiracy, which they did not prove after all.

He posted a meme, and the court said that was a completely legal thing to do. The prosecutors, trial judge, and jury were probably all Trump-haters. Individuals can now post memes again.

It of course said no such thing.

"they saw more than just a jokester."

NYC jury. Dude had zero chance.

Yep. These are the people who overwhelmingly voted for Harris.

And here we have people who don't know how jury selection works.

Or rather, they don't care; they just want their own judgement in place of the jury, so even the weakest delegitimization will do.

It's a great way to spot tools.

Or, you could just look in the mirror.

LMFAO

How do you think the case would have gone if there weren't serious free-speech issues?

To answer my own rhetorical question in a complete lack of style or grace, the circuit courts bend over backwards to convict defendants over meritorious jury-charge and sufficiency-of-the-evidence claims. If he had presented only a sufficiency argument, it strikes me as extremely unlikely that he would have prevailed. Dismissing the case on sufficiency grounds lets you dodge the constitutional issues. I would read it as a clear win for free-speech—or possibly venue limitations in internet-based cases, since that was another real issue with serious implications in other circumstances. It's just that you can't actually cite it for either proposition.

Right. Sufficiency of the evidence arguments are always losers. The jury was properly instructed? Well, we respect our jury system and will not go behind their thought process and second guess their decision. Conviction affirmed.

This smacks of wanting to dispose of the case without reaching the 1A question.

"The ruling had nothing to do with free speech. Indeed, a jury convicted him, meaning they saw more than just a jokester.

He got sprung because the federal law required a conspiracy, which they did not prove after all."

As has been stated multiple times already.

But we know exactly why a prosecution was undertaken in the first place, which was precisely because of 1A protected speech he was making, and so the government twisted the case until they had something to get him with. 'Conspiracy' to commit a perfectly legal act should not constitute criminal conspiracy.

You are entirely begging the question.

Sure. But you argue that to an audience baffled by what, "begging the question" means.

I get that, "usages change," mavens want that term either to have two meanings, or to discard its time-honored meaning. Problem is, to treat it that way deprives everyone of a field mark useful to recognize a particular kind of rhetorical incompetence.

Under 18 U.S.C.§956 it is a crime to conspire to murder, kidnap, or maim someone in another country even though the murder, kidnapping, or maiming would not itself be a U.S. federal crime.

If you wanna discuss the propriety of the feds making state things illegal by attaching "conspiracy" to it (or "crossing state lines", for that matter) you have a sympathetic ear, but that is a separate issue.

Interesting that Eugene congratulated prosecutors in his post-conviction article, but doesn't congratulate Mackey or his attorneys following reversal.

Why is that interesting? A year or two ago, Prof. Volokh stopped congratulating winning attorneys and simply started acknowledging them.

Question for all involved in this discussion:

Does the DOJ serve the law or the executive branch’s political priorities?

Formally and legally: The DOJ serves the law and the public interest, not the President’s political agenda.

Functionally and institutionally: The DOJ reflects the executive branch’s priorities but must uphold the rule of law and maintain prosecutorial independence.

Is the system working as it is meant to or is it functionally politicized?

My personal opinion is that the DOJ has become more and more politicized over time. I know most of the DOJ’s work is non-political and professional. Day-to-day law enforcement and prosecution decisions are made by civil servants, often with no regard to politics.

I also know political influence tends to rise in high-stakes or high-profile cases. Both Democratic and Republican administrations have faced accusations of politicizing the DOJ:

• Nixon’s “Saturday Night Massacre”

• Clinton-era independent counsel conflicts

• George W. Bush’s U.S. attorney firings

• Trump pressuring DOJ to pursue or drop investigations

• Biden critics alleging selective enforcement and lawfare

My conclusion: The DOJ often serves the law—but is vulnerable to serving political power when institutional guardrails fail.

If true, what remedy(s) prevents politicization?

I am going to say good appointees is no guarantee of anything so long as their tenure in office is subject to the will of the President.

Miachael D — Previously, oaths of office, pledging fealty to the Constitution, were the expected guardrails. They worked for a long time, while a vast majority of political actors took a sworn oath seriously.

But to rely on that to work without an explicit enforcement mechanism turns out to have been a Constitutional blunder. When they structured American government, the founders overlooked the possibility that political opportunism would become general among would-be office holders.

The founders well understood that men are not angels; they lacked experience to show that so concentrated a proportion of office seekers might turn out to be scoundrels. To the founders in their own time, it apparently seemed sensible that more-honorable leaders would sufficiently check the others.

A remedy readily available now would be a law passed by Congress to empower federal grand juries on their independent initiative to indict office holders for oath breaking. There would be need to exercise an acknowledged power to try such cases independent of all three branches of government.

To assemble political power sufficient to get that acknowledgement seems barely possible. It would likely require a time frame of multiple national administrations, and a continuous goad from dismaying political happenstance to do better. It is not easy to see how all those conditions could fit together constructively.

If it could be made to work, to keep that process clear of flagrant Constitutional abuse, remedies ought to be limited to disqualification from office. No loss of life, liberty, or property should be at stake.

To do it that way would piggyback the existing Congressional political power implicated in the impeachment process, and extend an explicitly limited part of that power to sworn tribunes of the jointly sovereign people themselves (which is what grand juries have always been, and still remain).

Trials beyond a reasonable doubt would stand as safeguards against political abuse—likely imperfect safeguards, but generally effective. To do it that way would reinforce founding era doctrine that to hold office is never a matter of right, but always a gift the people bestow at their pleasure. A verdict of oath breaking would thus become an incontrovertible finding of the people's displeasure, with a verdict of a broken oath defining unfitness for office.

Thus, today's polity would have to re-accustom itself to a founding era notion that to disqualify one among millions of candidates for office is not an earth-shaking rebuke to the people's joint constituent power. It is instead a reinforcement of the people's power to chose at pleasure what conduct qualifies—or disqualifies—a would-be office holder.

In exchange for an indispensably useful power to reassess an office-holder's fealty to his oath—and thus to encourage that fealty—the people would give up only an infinitesimal fraction of its power to choose who gets those gifts of office. And the tiny part given up would include much of popular politics' unfortunate tendency to encourage demagogues.

I think all that makes sense within a genuinely originalist interpretation of the Constitution, where assumption of a continuously active joint Popular sovereign was acknowledged. That kind of political use of grand jury power was likely precedented during the pre-founding era—although that would be a worthy subject still for separate historical examination. The practice I suggest was not in use, but other such political uses of grand juries, and also private prosecutions, were well known and frequently practiced.

Of course, during today's era—accustomed and inured to unbounded judicial power, and likewise a stranger to the notion of a continuously active joint popular sovereign—to do anything like I suggest by act of Congress would get an instant SCOTUS overturn. Which probably means an unlikely Constitutional amendment would be a practical requirement to get it done. For that ever to be a possibility will require a return to a less-divided national polity, while present circumstances may continue trending toward outcomes to preclude that.

I am not optimistic. I wish the founders had foreseen a need to enforce sovereign power against oath breakers.

Thank you for the thoughtful response. This is the type of logical response and analysis I am seeking.