The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The YIMBY Napkin

Checking the credibility of Hsieh-Moretti the lazy way. Third in a series of guest-blogging posts.

In 2019, Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti published "Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation" in the American Economic Journal. It's probably academia's most famous Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) article. H-M imagined a scenario where New York City and the Bay Area never imposed draconian housing regulation. Then they estimated how much bigger the U.S. economy would have been in this alternate history. Their answer was shocking. Restraining local regulation in just two keys localities would have made total U.S. GDP 4-9% higher.

The key idea: New York City and the Bay Area are the country's most productive areas. Given the same inputs, they yield an exceptionally large quantity of output. In economic jargon, they have sky-high Total Factor Productivity. With much less housing regulation, housing prices in these TFP-rich areas would be much lower. Their populations would, in turn, be much higher. Production would naturally fall in low-TFP regions, but rise far more in high-TFP regions. As a result, the total output of the country would rise.

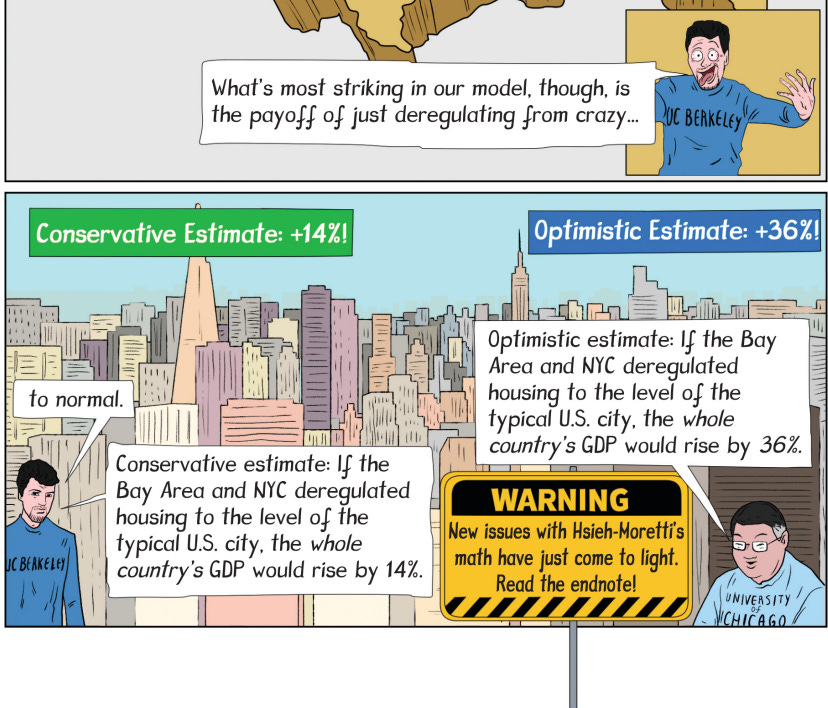

When writing Build, Baby, Build, I reviewed H-M closely. To my surprise, I discovered multiple arithmetic errors, which Hsieh and Moretti quickly acknowledged. Strangely, my corrections actually strengthened their results. Instead of implying that GDP would be 4-9% higher, their paper actually implies that GDP would be 14-36% higher. Super shocking!

Not long before my book went to print, however, economist Brian Greaney published a much more fundamental critique of H-M. This time, however, Hsieh and Moretti did not concede. Nor did Greaney. Given my time constraints, I decided to just insert a warning into the text and add a detailed endnote on the controversy. Like so:

Recently, however, I started wondering what a quick "back-of-the-envelope" or "napkin" calculation would reveal. When I teach the economic effects of immigration, for example, I normally start by multiplying rough estimates of (a) gains per immigrant by (b) total number of immigrants. In principle, one could do the same for domestic migration. Why not give it a try?

After looking for easily accessible data and weighing a few different approaches, I did the following.

- I found data on mean earnings by education by state (plus Washington, DC) in Table A6 of John Winters' "What You Make Depends on Where You Live: College Earnings Across State and Metropolitan Areas."

- To make life easier, I only did calculations for the "High School" and "Bachelor's Degree" calculations, and assumed that 2/3rds of workers were in the former category, and 1/3rd in the latter. Close enough.

- I coded the following as having "Bad Zoning": California, Connecticut, DC, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island.

- I calculated population-weighted average mean earnings in Bad Zoning states, and assumed that post-deregulation migration into the Bad Zoning states would be proportional to their existing populations.

- I assumed that if Bad Zoning were ended, the fraction of workers who would move was directly proportion to the percentage wage gain for their educational category.

- I set an elasticity of .2, which implies that a 5% wage gain would induce 1% of workers to move.

- Snapping these pieces together, I calculated per-worker annual dollar gains for both educational categories for all states. If a mover gains $5000, but only 2% of workers would actually move, the per-worker gain is $100.

- I can use population weights to calculate per-worker gains for the whole country. If, for example, there were two states total, one with 1M people and the other with $99M, the per-worker gains for the country would be 1% times the gain in the first state plus 99% times the gain in the second state.

Since this was too much to actually write on a napkin, I set it all up as a simple Google Sheet, which you can view (and tinker with!) here. Obviously you can lodge dozens of complaints about what I did, but I'm just going for basic plausibility.

Here's what I found: Under my assumptions, GDP rises by $532 per worker, about +.8%. Much lower than H-M's original lower bound of +4%. A lot in absolute terms, but nothing transformative.

How sensitive are the results to the assumptions?

- The gains are directly proportional to the elasticity of .2 that I set in Assumption #6. If you think that a 1% wage gain will prompt 1% of workers to move, H-M's initial lower bound is correct. But that seems crazy high.

- I used state-level data because it was easier. But Table 11 in "What You Make Depends on Where You Live" has data on income by education for 104 metropolitan areas (MSAs). The poorest metropolitan areas are almost as poor as the poorest states, but the richest metropolitan areas are markedly richer than the richest states. The non-metropolitan areas would generally be poorer still.

- Upshot: A thought experiment where housing deregulation causes movement to the very richest metropolitan areas (rather than just the richest states) could plausibly yield gains twice as large as my initial estimates. If you want to do the actual work, I'll gladly run it as a guest post on my Substack.

Why are estimates of the domestic migration gains so much smaller than estimates of international migration gains?

First, because gains per capita are so much larger internationally. As Clemens, Montenegro, and Pritchett (CMP) show, immigrants from the Third World to the U.S. routinely multiply their income by a factor of 5 or 10. In contrast, moving from the very poorest MSA (El Paso, Texas) to the very richest (Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, Connecticut) multiplies high school earnings by 1.6 and college earnings by 2.7. The biggest intra-national gains are about as big as the smallest international gains in CMP.

Second, because far more people want to migrate internationally. Massive gains motivate billions. Moderate gains motivate only millions, or perhaps tens of millions. Big times big is massive, but moderate times moderate remains moderate.

The lesson: Hsieh and Moretti's initial estimates were always implausibly large. When I corrected their math, yielding even bigger estimated effects, I should have taken out a napkin for a quick plausibility check.

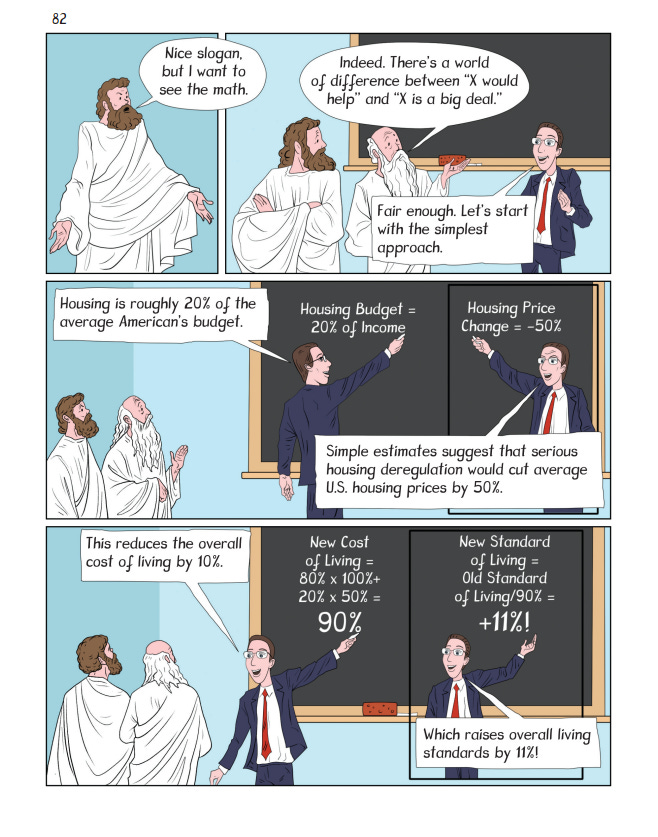

Fortunately, I have another napkin. A better napkin. The cleanest, clearest case for YIMBY is simply that (a) housing deregulation would sharply reduce housing prices (by about 50%), and (b) housing is a large share of the household budget (about 20%). So deregulation would ultimately cut the cost of living by 10% — and raise living standards by 11%. (Read the book for details).

I'll never get in the American Economic Journal with this argument, but I say it's solid.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"The key idea: New York City and the Bay Area are the country's most productive areas. Given the same inputs, they yield an exceptionally large quantity of output. In economic jargon, they have sky-high Total Factor Productivity. With much less housing regulation, housing prices in these TFP-rich areas would be much lower. Their populations would, in turn, be much higher. Production would naturally fall in low-TFP regions, but rise far more in high-TFP regions. As a result, the total output of the country would rise."

You know, this does not really follow.

In a high cost area, the only things you CAN viably do are things that are highly productive, but which sort of have to be in that location. So if a high cost area is going to be doing anything, it's going to be doing highly productive stuff. Given costs in Manhattan, if you could do it someplace else you would, and if it wasn't productive enough to be viable in Manhattan, you simply wouldn't do it.

This doesn't mean that if you lower the costs, the productivity would stay constant, but more would get done. It means that the things you for some reason had to do there would be more profitable, but also that you could stop obsessing quite so much about being productive, and average productivity would probably drop.

There would be a substantial gain, of course, but not to the degree a simple linear analysis would predict.

" . . . if you could do it someplace else you would . . . . "

You're missing the historical side.

SF and NY are the significant places they are (and not Lincoln, NE or Helena, MT), because they were port cities.

So trade, banking, insurance, taxes, regulations, unions, etc., etc., grew up there and are well established.

Of course, quality-of-life projects then developed (housing, arts, food, entertainments, health services, etc.), too.

So now it's hard to transplant all that.

Sure, in the 21st century, you can do 95% of work on-line.

But there's no way Lincoln or Helena can match SF or NY for quality of life things listed above (and yes, some folks like the rural life - but obviously not enough).

Maybe we'll change someday but not right now.

What does that have to do with Brett Bellmore's point?

As far as I can tell he's actually agreeing with me. Though he might not realize it.

I don't quite get this "key point" either.

What is missing from Caplan's argument is any sort of intuitive explanation of why this would happen.

Imagine a highly productive individual - a neurosurgeon maybe - who lives and works in Kansas City. Dr. Skull has some interest in moving to NYC, but is deterred by high housing costs.

Now housing costs drop dramatically, so Skull picks himself up and goes. How has he become more productive? Don't tell me he can charge more, which is nice for him and raises GDP, but that's a flaw in GDP as a measure of wellbeing, not a cause for celebration. How has real GDP increased?

Maybe it has, and Caplan has an explanation. I'd like to hear it.

Oh, and it's typically "YIYBY", not "YIMBY"; "Yes In Your Back Yard".

So you keep insisting.

So I keep observing.

What would be one of the strongest pieces of evidence you'd point a skeptical interlocutor towards that supports that position?

The primary regulatory impediment to more and allegedly lower-cost housing in the Bay Area is the removal of vast swaths of land from development. Most Bay Area land is protected open space, and no one wants to change this status quo.

Unsurprisingly, people who live in $10 million homes really enjoy having national parks in their backyards.

Instead, Bay Area pro-housing activists are exclusively pro-density activists. Building in and around the neighborhoods of the ultra-wealthy isn’t progress—it’s urban sprawl. And the cities these activists target for higher density are always the (relatively) poorest: Oakland and East Palo Alto. Never Atherton or Woodside.

So at least here in the Bay Area, it is very much YIYBY and not YIMBY.

See https://www.mercurynews.com/2024/04/21/its-not-just-skyscrapers-and-high-density-builders-remedy-is-also-bringing-more-urban-sprawl/

At times, it's high density, but not even yiyby, witness how the so-called yimbys screamed when news of the new town near Travis AFB was announced. they were incensed with it, because it wasn't going to be high density urban housing in SF.

(And near as I can tell, the nimbys were all in favor of it.)

And so YOU keep insisting, without any reasoning to back it up, meaning you have nothing and are just sniping.

Thank you for your honesty.

Burden is on the person making the assertion, chief.

All I'm doing is pointing out that burden is not met.

"Chief"???

You're Native Amurican now? or Appropriating an Injun word, which is even worse, I know Wigger is a young White guy who tries to talk Black, but what's the name for a White guy trying to talk like a Redskin? Nice thing about speaking Engrish as a second language, you might never get "its/it's, to/too" right, but you never pick up those filler idiotic words, like "Chief" "Bubba" and my favorite E-bonics phrase

"Nome Sane?"

Frank

Hasn’t Bryan ever heard of the government multiplier?

When the people in government, they are so wise and efficient that their spending $1 is equivalent to them spending $1.76 in our economy. Now that’s bang for you buck!

When you and I spend money, we’re just boobs and nitwits, when we spend money it’s equivalent to $.70 🙁 *sad trombone*!

The best, most rocketing, most successful economy possible (by definition) is one where the people in government spend ALL our money! We’d instantly double our economic productivity OVERNIGHT! Don’t forget, it would be super inclusive and equitable too! Double output AND social justice! “Washington D.C.”? No, that’s not the best description… “Utopia”, YES!

All Praise The Bureaucrats!

Thanks Be To The State!

The State is Great!

"All Praise The Bureaucrats!

Thanks Be To The State!

The State is Great!"

Nice try, but you are still going up against the wall.

That's what I get for being a Normal... Just like during the French Revolution, Red Terror, Cultural Revolution, Bolshevik Revolution or any other Democrat-adjacent revolution.

Anti-government cranks are not normal. Not nearly.

https://imgb.ifunny.co/images/89cc511271cf3109d388ad71c538ca9b20c3d57d8d264e3dd38181b3e25daf67_1.webp

It does seem a little strange that two of the three posts on this book are about things the author thinks are wrong with it.

Kinda refreshing that he's willing to publicly admit mistakes, isn't it?

I'm not complaining (though his publisher might be!). Just noting that it's a bit unusual.

Actually, I find it quite charming.

I suspect it is the fundamental difference between the honest explorer and the partizan hack. The honest explorer thinks problems and confounding features should be front and center. That way they can be explained/mitigated and we can get closer to “the truth”. The partizan hack thinks problems and confounding features should be buried in a shallow grave in the backyard so they are out of sight and don’t confound the narrative.

Bespeaks an artistic temperament.

NY and California are trading on history. But it takes a while to fall all the way back down - they're still eating in England I believe.

Anyway the politicians of NY and California are doing the investors of new capital a big favor by scaring them away.

Two ports that quickly grew gigantic serving a continent, and became centers of other things as well, general industry, financials.

As throughout all human history, bloated corruption moves in, attaching itself like parasitic moss on a tree, and ultimately declares itself the cause of the financial success.

"they have sky-high Total Factor Productivity. With much less housing regulation, housing prices in these TFP-rich areas would be much lower. Their populations would, in turn, be much higher."

Yes. This is due to the TFP-rich soil in those areas. It is like magic dirt. All you need to do is stack more bodies on this special earth, any bodies, and the more bodies you stack, the more productivity you get linearly.

These are the people that believe zip codes have a magic power that raises good children so they are forcing mixed zoning in all the White suburbs.

You know, M.L., At this point I tend to agree with you.

It's a complex model, and will take a while to understand (and to be honest, I doubt I'll give it the necessary effort.)

Still this TFP business, which seems to drive the model could use a lot more explanation. It strikes me, as it does you, that it's a sort of magical quality that some places have and others don't, for who knows what reason.

Anyway, I agree that Government Bad. Why did NYC need that silly Erie Canal, anyway?

People in NY and SF pay a lot to live there, and they have passed zoning laws to keep it the way they like it. But Caplan argues that they would be better off if their homes were like Houston. I don't see how any argument like this will show that they will be more productive in a Houston-like city.

Bad assumptions all around

If it were at all true, then high regulation states would not continue to be wealthy and productive.

Low regulation states are seeing growth, but not productivity

I see no reason to believe that lower housing prices in NY would...wait, I see no reason to believe more housing would lower prices in NY, more people would move there, so NY would create more GDP, but North Carolina[for instance] would see lower housing prices because no one would move there.

Typical 'if you change one thing but everything else will remain the same' thinking