The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Professor Akhil Amar, On His Podcast, Responds to Attorney General Mukasey and the Tillman-Blackman Position

Section 3 civility outside and inside Yale Law School.

[This post is co-authored with Professor Seth Barrett Tillman]

The sequence of events over the past week could not have been scripted. On Thursday, September 7, former-federal judge, and former-Attorney General Michael Mukasey published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, contending that the President was not an "Officer of the United States" for purposes of Section 3. We had no clue this piece was coming, and we were pleasantly surprised to see that his thinking aligned with our own. At that point, we were nearing completion of our draft article on Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. We added a new footnote referencing Mukasey's op-ed, but otherwise we planned to spend the next few days finalizing our draft article. The document was finalized late in the evening of Monday, September 11, and was posted to SSRN shortly after midnight. On the afternoon of Tuesday, September 12, Professor Steve Calabresi's letter to the editor ran in the Wall Street Journal. Calabresi also concluded that the President is not an "Officer of the United States" for purposes of Section 3. When Steve had submitted his letter, he had not yet seen our new article on Section 3. And we had no clue Steve would publish that view in the WSJ. Here again we were pleasantly surprised.

After we saw Calabresi's letter, our minds turned to Yale Law Professor Akhil Reed Amar. Amar and Calabresi are long-time friends, have taught a class together at Yale, regularly cite and respond to each other's material, and are co-authors of a leading constitutional law treatise. We realized that Calabresi's position was now in tension with Amar's position. Nearly three decades ago, Vikram and Akhil Amar argued that there is no difference between "Officers of the United States" and "Office[s] . . . under the United States," and the President is covered by both phrases.

Then, on Wednesday, September 13, Amar released a new podcast about Section 3. The podcast only references Mukasey's op-ed. It does not address the Blackman-Tillman article, or Calabresi's letter to the editor. (We suspect it was recorded at some point after Thursday, September 7, and before Tuesday, September 12.) Amar criticizes Mukasey, as well as the amicus brief that Tillman and Blackman submitted in 2017 for the Emoluments Clauses litigation. We are pleased that after six years our amicus brief in district court litigation is known to the world.

Today is Thursday, September 14. And now, all these threads are starting to come together in unexpected ways.

We encourage you to listen to Amar's podcast where he is interviewed by Andy Lipka. In particular, jump to roughly the 1:08:00 mark, where he spends 20 minutes talking about Mukasey and the Tillman-Blackman position. We commend Amar for stating clearly and directly what he thinks about Mukasey and our position. Here are a few highlights, with timestamps. (We add our comments in italics within brackets.)

- "And I was laughing, because I actually couldn't resist because to even hear these formulations elicits laughter from me." (7:31).

- "This was not ex-General Mukasey's finest moment." (1:06:40).

- "The Tillman-Blackman position, which I think is daft …" (1:10:04).

- "This one was just a brief by Tillman. Maybe Blackman wasn't involved in the brief, but see brief for scholar Seth Barrett Tillman." (1:12:14). [If you check the front cover of the brief, and the signature block, Blackman's name was listed as counsel.]

- On the Tillman-Blackman position: "I actually didn't think it was worth the audience's time. I thought it was such a ridiculous point." [Here, Amar was referring to his two earlier podcasts in which he interviewed Professors Will Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen.]

- "Will Baude clerked for Chief Justice John Roberts and is among the most distinguished scholars there is. He is the single most cited young scholar by the Supreme Court, Will Baude, Roberts clerk. Sai Prakash is the most cited the younger-ish scholar by the Supreme Court and he clerked for Thomas, these are very credible people you see who are really experts truthfully, and that's less true of Professor Tillman. Truth be told, [Tillman] who is not cited by the Supreme Court and in the one case where a court really turns and discusses his work, body slams him." (1:16:26). [We agree that Baude and Prakash are among the most distinguished legal scholars in the United States.]

- "Let me be clear, this is a genuinely stupid argument on the merits, I'm going to demolish it. It's embarrassing that someone so distinguished [as Mukasey] at the end of, you know, near the end of their career would say something like this and so prominent to place." (1:18:13). [This Erev Rosh Hashanah, we wish General Mukasey a long and healthy life.]

- "This is very wrong. It's silly. It's so silly that we didn't spend time on it in three hours with Baude and Paulsen because I moved beyond it because it seemed to me they were just pushing on an open door." (1:22:11).

- "Truthfully, this is not true of all great lawyers and judges who aren't scholars they have sometimes underlings write stuff for them. Judges have law clerks, lawyers have associates, great lawyers have staff attorneys who do this. So it's possible that General Mukasey did all this himself, but it's possible that some underling, and he offered his name he [is] still responsible for it." (1:23:06).

- "But when a scholar says something, typically, that scholar did it himself, herself is responsible for it. And especially if that scholar is building on a lifetime of scholarship on, let's say, the Constitution, in general, I'm going to give more benefit of the doubt to the scholar, and they have two scholars like Sai Prakash, and Will Baude and Mike Paulsen and Larry Tribe. On the one side, Akhil and Vik[ram] have taken this position back in 1996, an article on presidential succession. And on the other side, we do have a scholar Seth Barrett Tillman, he has a track record of citation or non citation, you can judge it for yourself. I don't think it's a very distinguished record truthfully. And, and you have General Mukasey, but I think this is not his finest hour." (1:23:29). [Query: What is a record of non-citation?]

- "But what I'm saying is that he's [Mukasey] written no article that I know of in which he elaborates all this. I know where it's coming from. It's coming from Seth Barrett Tillman, which has been properly body slammed by Sai Prakash and judges and Baude and Paulsen so and Tribe himself was involved in that Emoluments Clause litigation on the other side, and I hold I don't always agree with Larry Tribe, I don't always agree with with Sai Prakash or Will Baude, our audience has heard that, but these are the serious people. That's why these are the serious people that you've heard from on our podcast." (1:25:31).

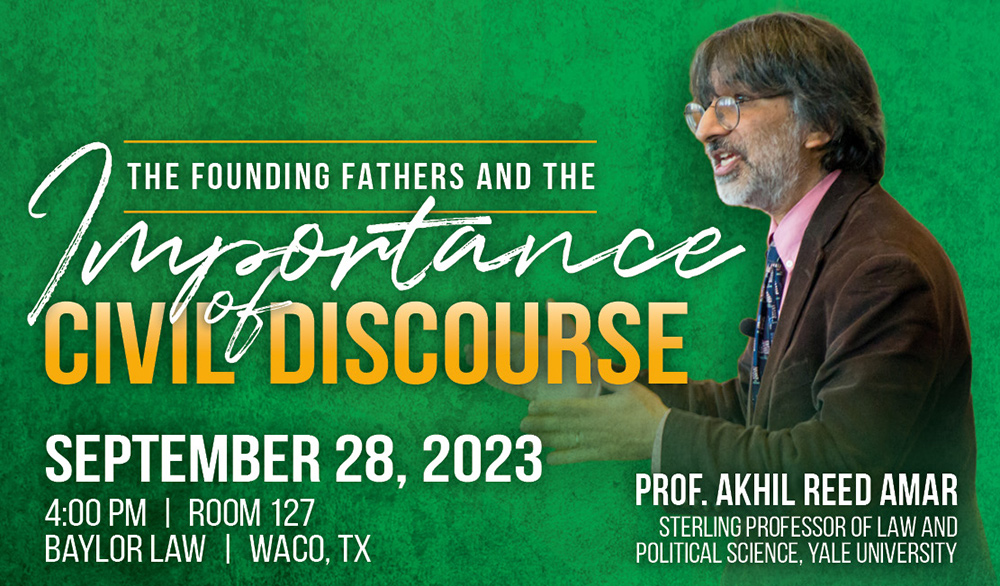

If we may offer a shameless plug, on September 28, Amar is giving a lecture on the importance of civil discourse at Baylor Law School.

Amar likely thinks that his podcast is consistent with his views on the importance of civil discourse. He describes a scholarly exchange like a cage match--"body slam"! He repeated, over and over again, that authors he agrees with clerked on the Supreme Court, but Tillman did not. And he stated that Tillman is less credible than those former Supreme Court clerks. He called positions he disagrees with "daft," "stupid," "embarrassing," "silly," and so on. He accuses Tillman of improperly leading astray a former Attorney General--almost like Rasputin. On the basis of no information, Amar accuses Mukasey of using an "underling" ghostwriter, or lifting ideas from Tillman without attribution, or both. Mukasey came to these conclusions on his own. We know this because after his op-ed was published, we initiated a correspondence with him. Furthermore, the fact that Mukasey came to these conclusions on his own demonstrates the strength of the ideas we have put forward. Moreover, we don't proclaim, nor have we ever proclaimed, that the ideas we have presented originate with us. We in turn rely on older sources, including Alexander Hamilton, Justice Story, and many others.

To be clear, we have no objection with Amar's language. Indeed, we applaud his willingness to be direct and clear and to embrace being controversial. This is civility as Amar sees things.

We add a note of caution. Amar is a full professor with tenure at a law school with a sizable endowment. For him, there are no downside consequences to using strong language. In fact, there is only an upside for him personally. We worry that some law students, and perhaps others, who are young, and less sophisticated than Amar, might emulate this behavior. Later in life, they may discover that future would-be employers, including government employers, will check would-be employees' social media footprints. Many employers will shy away from candidates who use such language. As a result, these people may find themselves disadvantaged for doing what Amar has done. We hope we are wrong about this, but we fear that we are right.

Today is only Thursday. What Section 3 shoe will drop next? We have been to this rodeo before. People who have disagreed with us have later walked back their comments in one way or another. This happened on several occasions. There are many such people we could cite. One of them is Professor Laurence Tribe. We single out Tribe here only because Amar mentions Tribe in his podcast.

Must apologize: turns out scholar @SethBTillman makes that argument carefully. He's no kook, but I find the argument seriously unconvincing. https://t.co/EU7YVuWCRK

— Laurence Tribe ???????? ⚖️ (@tribelaw) November 22, 2016

It is never too late to reconsider things. It is a good thing to reopen intellectual issues from time-to-time. And that's what Professor Tribe did in 2016. And that's what Profesor Calabresi did this week. We make no prediction whether Professor Amar will follow Professor Tribe or Professor Calabresi's example. But we are hopeful.

We have our own views with regard to how intellectual debate on legal issues should take place. Circa 2008, when Tillman first began to publish on this topic: i.e., the scope of the Constitution's "office"- and "officer"-language, he actively sought out and solicited responses from Professors Calabresi, Prakash, Zephyr Teachout, and others. That's the actual origin of the Prakash article that Professor Amar favorably cites. When we have cited to our views, we regularly also cite to theirs--so that our readers can see all sides represented by their best proponents. We notice that on Professor Amar's website, he does not follow this practice. He only links to articles supporting the views he believes to be correct. We don't say that he is wrong to do so. We only point out that this is his practice. You must decide for yourself what is the better practice.

Professor Amar, who said the Tillman-Blackman position is inconsistent with what Hamilton thought (1:13:24), would be well-served to check what Hamilton actually wrote. For a good place to start, see parts one through four of our ten-part series in the South Texas Law Review (1, 2, 3, 4), as well as our article in the NYU Journal of Law & Liberty. We look forward to the Amar podcast that addresses our daft article--sorry, that should be draft article. How embarrassing.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Professor Amar, who said the Tillman-Blackman position is inconsistent with what Hamilton thought (1:13:24), would be well-served to check what Hamilton actually wrote.

It's fair to say that Hamilton's advocacy is more enigmatic at times than almost any other founder's. In the Federalist papers he wrote in support of militia virtues which during the rest of his career he tended to deny. Hamilton's support of a standing army during the Adams administration is also notably divergent from his advocacy during the ratification debates.

If Amar—one of the few constitutional experts practicing who clearly knows something about history—characterizes Hamilton's thought generally, and Blackman, who seems to know nothing about history, disagrees on the basis of what may be citation to disingenuous advocacy by Hamilton, it would be unwise to rely uncritically on Blackman's interpretation.

https://memeguy.com/photos/images/lick-the-bowl-clean-467454.png

Mark Graber's post at Balkinization, Section Three "Of" and "Under" Nonsense: The Sequel is on point and suggests your views have some serous defects. An actual historian doing history.

Yeah, I was about to point that out.

Section Three "Of" and "Under" Nonsense: The Sequel

Thanks for the link, Brett.

Offhand, I'd say Graber makes a very strong case that the whole "of/under/not" business is silly.

If these distinctions were intended, then surely they could have been made more clearly and explicitly.

Yeah, I think it's a silly argument, too. The very second sentence in Article 2 reads, "He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years,"

He holds an office, but he's not an officer? Give me a break.

Academics seem to love taking contrarian positions and defending them. Admittedly it can be fun, but don't take it so seriously when you do!

Josh,

The overall point about civility is, of course, a laudable goal. And it's always good to commend *anyone* of any stripe, when he or she has the integrity to change a position. Changing one's mind in response to new information or data is a sign of strength, not weakness.

With that in mind; can you provide, say, two examples in your own life where you started with a conservative position, and then changed to a liberal position, based on your new information? From you thousands of posts, I expect that there will be dozens of examples that you can provide. Just a few will be fine.

Thanks in advance for your prompt attention. 🙂

Changing one’s mind in response to new information or data is a sign of strength, not weakness. With that in mind; can you provide, say, two examples in your own life where you started with a conservative position, and then changed to a liberal position, based on your new information?

1. Why would a change from a conservative position to a liberal position be required as an indication of open-mindedness ? Would not a change in the opposite direction do just as well ? Perhaps Blackman started out as a common or garden agitprop student radical.

2. Typically, on average, and statistically speaking* conservative positions value experience and the accommodation of ideas to reality, whereas liberal positions typically applaud the shinyness of new (or at least recently absorbed) ideas. Thus the changing of the mind in response to new information (or old information that you were unaware of when your original opinion was cast) typically betokens a change in the liberal => conservative direction.

* horror at generalisation and stereotype is generally (sic) a disease of youth. Experience teaches us that generalisations and sterotypes abound because, generally speaking, they accord with reality. On average and statistically speaking, of course.

3. As I understand it, Blackman claims to have been persuaded of Tillman's view on the menagerie of constitutional "officers" 10 years ago, long before it acquired any political salience. So it's hardly a left-right question. It's a Nerd Special question.

4. All that said, Blackman's writing does carry a whiff of the insistent certainty of the opinionated teenager. I have often wondered if he and Greta Thunberg might be related.

You know, I don't think of Greta much these days.

But the conservative nemesis factory turns out products that last!

The rest of your post is a longwinded way of saying reality has a conservative bias. You try too hard.

conservative positions value experience and the accommodation of ideas to reality, whereas liberal positions typically applaud the shinyness of new

Or conservatives fear change and their positions tend to value a past that does not exist over a reality that does. [Not saying this is a correct generalization, but it's got some anecdotes and is the same kind of airy generalization as the OP]

Experience teaches us that generalizations and stereotypes abound because, generally speaking, they accord with reality

America is pretty into judging an individual on their own merits, actually.

As I understand it, Blackman claims

Well, there's a problem.

I disagree. I think he's just saying that conservative ideas tend to be more static than liberal ideas, which is another way of saying that conservatives are less open-minded than liberals. Checks out to me.

Conservatism values established tradition as hard-wrought wisdom. It doesn’t say it should not be changed, only done so after much deliberation.

Liberalism believes there should be large breaks with the past to save society from itself.

Your statement about open-mindedness is little more than those who disagree with me are stupid. One could just as easily say modern liberals are weak-minded, easily susceptible to demagoguery trying to aggrandize its power through large, quick changes to the law.

Liberalism believes there should be large breaks with the past to save society from itself.

No, that's radicalism; you're on the wrong axis.

You are confusing radical-conservative with liberal-conservative.

Different uses of the word conservative. Political conservativism in America has long ago left Burke.

These days, conservatives in America are the radicals.

"These days, conservatives in America are the radicals."

These are just word games.

But certainly, Burke would have been appalled by MAGAism.

How in the world is it a word game?

Radical is a real word that means things and describes the GOP/conservatives more than the Dems/liberals right now.

I think it’s obvious whose weak minds are susceptible to demagoguery.

But I think that’s too harsh. MAGA’s susceptibility isn’t primarily due to being weak-minded. It’s a combination of two things.

First is the observation that conservatives are driven by fear and progressives are driven by hope. That’s the root of all the distinctions we’ve been discussing.

Second is MAGA’s relentless focus on grievances, which breeds alienation.

As Bannon observed like 10 years ago and made a political career out of, fear + alienation = susceptibility to demagoguery aka cult.

Typically, on average, and statistically speaking* conservative positions value experience and the accommodation of ideas to reality,

This has not been my observation.

No serious person would publish a call for civility (or swipe at others with respect to that issue) at the Volokh Conspiracy, which regularly features

vile racial slurs (habitually used by the proprietor, who has established a bigot-hugging tone enthusiastically embraced by a carefully cultivated collection of disaffected, roundly bigoted conservative commenters);

calls for liberal judges to be gassed;

calls for non-conservatives to be shot in the face as they open front doors;

support for violent insurrectionists;

calls for liberals to be sent to Zyklon showers;

partisan, viewpoint-driven censorship;

calls for liberals to be placed face-down in landfills;

threats to achieve conservative goals using "Second Amendment solutions," another civil war, militia actions, violence in the streets, and the like;

calls for non-conservatives to be pushed through woodchippers;

calls for liberals to be raped;

and

an incessant stream of slur-laden bigotry targeting gays, Blacks, women, Jews, transgender persons, Muslims, and others.

If any of the spineless, polemical law professors who operate this blog wish to try to correct the record regarding my description of their bigot-hugging blog and its downscale, deplorable target audience, please do so here:

.

.

.

.

.

.

#Cowards #Hypocrites #Misfits #Losers

Isn't Tribe the guy who was horrendously wrong about student loan forgiveness and the eviction moratorium?

It's very kind of you to limit the list of Tribe's wrongness to two items: presenting the full list would seem mean-spirited.

Many in the academy argue that professing wrongness is merely a part of the job... an element of the so-called academic freedom demanded by the big-money union corporation they represent. In contrast, those outside the academy actually responsible for creating, protecting, and defending the law see such wrongness as the clucking of fowl: borrowing from Millay, the gabble and hiss of the academy's unheroic geese is notable, but not noteworthy.

I'm sorry to say it, but this stuff about how Section 3 excludes people from being Presidential electors or postmasters because they were insurrectionists or aided the enemy, while allowing these same people to be President...this sort of argument sounds like something a satirist might write if he was making fun of lawyers.

If originalism or textualism requires rummaging through impeachment debates, officeholding sections in the original Constitution, and the like, rather than simply enforcing the obvious meaning of Section 3, then maybe originalism and textualism are wrong. Look at Section 3 based on the basic premises of republican (small "r") government and explain how someone who isn't trusted to serve as state agriculture commissioner is still trusted to serve as President of the United States.

I agree... to a point: the trust issue is real and ultimately The People must interpret every element of the Constitution. "The people can undoubtedly overthrow a constitution guarded by any number of any kind of limitations on the amending power and even by limitations on the people's power to overthrow it."

How can someone who is prohibited from serving as a state agriculture commissioner become President? Because The People say so.

How can one who is not trusted by the establishment in power become President? Perhaps because The People _trust_ that Presidential candidate more than they trust the establishment in power... and the establishment which penned a poorly worded, purposely vindictive rule.

The question is what the People said. Section 3 may or may not apply to Trump – opposition from the establishment isn’t enough to be legally disqualified.

But I can’t see how the words the people used could, in light of the mischief Section 3 was aimed at, be deemed to apply to postmasters and not Presidents.

The supposedly bad motives of Sec. 3’s drafters don’t exempt us from trying to figure out the meaning of the words they used, using fairly standard methods of interpretation.

I hope Trump has other defenses, because this one makes a mockery of the Constitution.

(As for vindictiveness, most Confederates affected by Sec. 3 only had to “suffer” for four years - 1868-1872 - after which they got their political standing back. Only a small group of the worst offenders were kept on the naughty list, and many of them obtained Congressional pardons later. The few who were still on the naughty list in 1898 got their rights restored in the patriotic enthusiasm of the Spanish-American War)

But I can’t see how the words the people used could, in light of the mischief Section 3 was aimed at, be deemed to apply to postmasters and not Presidents.

What mischief do you think Section 3 is getting at ?

It seems to me that, at least on its face, it is not aimed at the mischief of keeping insurrectionists and rebels out of federal and state offices, and so, a fortiori, the more important the office, the more important that they be kept out of it. If this was the mischief then the ban would not be confined to people who had taken - as Senators, officers etc - an oath to support the Constitution of the United States.

So the mischief seems more to punish the forsworn than to protect the Republic from rebels and insurrectionists. The importance of the office is irrelevant to this.

I don't know how many of the founding fathers might previously have taken an oath of allegiance to the King - maybe not many.

If so, perhaps aiming Section 3 of the 14th Amendment at oath-breakers rather than rebels per se was intended as an act of delicacy to avoid appearing to be hypocritical by making a stink about insurrection and rebellion - which the Declaration of Independence celebrates and justifies - rather than about oath-breaking, which is not so celebrated.

So perhaps the real mischief at which Section 3 is getting - rebellion - is concealed behind a surrogate mischief - oath-breaking.

"If this was the mischief then the ban would not be confined to people who had taken – as Senators, officers etc – an oath to support the Constitution of the United States."

Or maybe it WAS about oath breaking.

You take an oath to the Constitution, and the government under it, and are forsworn. How could you ever qualify to assume any office that required you to again take such an oath? Your word was proven worthless! (This was my own argument back during the Clinton impeachment, about why perjury actually was a valid ground for impeachment.)

Reasonable people could differ about whether the Confederacy had the right to secede, but once you'd taken an oath to the federal government, you'd given up your right to differ on that point, or so they could argue.

Bellmore, Lincoln, for instance, took an oath. He did not take an oath to the government. He swore an oath to execute faithfully the office of President, which he understood as the gift of the jointly sovereign People. Likewise, Lincoln swore to protect and defend the Constitution—the jointly sovereign People's decree to constitute, empower and constrain government. Lincoln understood that the oath of the President is always, first and foremost, an oath of allegiance to this nation's joint popular sovereign.

“insurrection and rebellion – which the Declaration of Independence celebrates and justifies”

Rebellion *against tyrants,* not generic rebellion. And only if nonviolent means prove unavailing. Kind of like the "just war" doctrine.

Putting the federal government on a slavery-skeptical basis (Lincoln’s platform) isn’t tyranny, the tyranny was the pre-Lincoln federal policy of *promoting* slavery.

To be sure, Sec. 3 codified the belief that rebelling against the U. S. government isn’t justified, but if rebellion is ever justified (which God forbid), then the rebels would have to risk the penalties affixed to the defeated party if they lose – which in the case of a true tyranny would go way beyond exclusion from office.

The oath-breakers targeted by Art. 3 did the opposite of the thing they promised to do (uphold the Constitution), an offense worse, if anything, on the part of the President than on the part of a postmaster.

Postmasters are appointed not elected – that’s a significant difference.

The positions mentioned specifically in Section 3 are all elected by the individual states or appointed by their legislatures.

The President, on the other hand, is elected by the nation with population being the primary determination of voting weight (albeit, with most states having adopted a “winner takes all” EC approach, this isn’t as true as one might like).

That’s seems more likely to me, a layperson, to explain the oddity of listing Senators and Representatives but not President than an explanation that the scribe was tired or running out of ink so left out “President” and no one noticed.

Even the explicit inclusion of Senator and Representative suggest these might not be covered by being an "office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State" - in which case it would be hard to justify why "President' would be such an "office".

“sounds like something a satirist might write . . . explain how someone who isn’t trusted to serve as state agriculture commissioner is still trusted to serve as President”

I think you are looking at it the wrong way. Trusted by who, exactly? To insert a clause like this in the Constitution is to give judges, and maybe secretaries of state and others, decision making power over who gets to be elected. Isn’t it pretty easy to see why one might support or acquiesce to such antidemocratic controls over the office of agricultural commissioner, while not applying the same to that of the President? I don't know which position is correct but it seems like a fair question.

I admit I hadn't thought of it that way before. My solution would be to allow citizen suits in a special federal court against alleged Art. 3 violators who are still in politics - informer's fees for plaintiff if he wins, compensation to defendant if plaintiff loses. And have a speedy hearing.

Margrave, generalize that insight and you would arrive at a remedy for one of the primary original defects in American constitutionalism. The founders predicated their system of government on a notion of a continuously active joint popular sovereign. They blundered, however, when they failed to institutionalize that sovereignty as an enduring institutional power at the top of their constitutional structure.

The founders literally thought of their popular sovereignty as, by analogy, an entity with king-like powers and prerogatives. They understood their new system of government based on those powers as an advance in political philosophy. They supposed with good reason (but also with worried skepticism) that their invention of a popular sovereign would correct for all time the well-understood defect of reliance on the good will of a king as sovereign, whose interests might not reliably align with the interests of his subjects.

But when the founders trusted the structure of government set forward in the Constitution as the sole bulwark of the People's own power to rule at pleasure and without constraint, they erred. They may not have erred by much. It took a long time for American constitutionalism to degrade to its presently imperiled condition.

But the fact is now evident. The essentially decapitated constitutionalism featured in the customary understanding of today's office holders and legal authorities lacks any institutional presence to cope with, for instance, otherwise unanswerable questions to say on what basis the 14th Amendment's section 3 can be enforced. That is a question which only a sovereign can properly address, and our current joint popular sovereign lacks any trustworthy institutional representation of its views to answer that need.

What seems needed is a Constitutional amendment to institutionalize an enduring sovereign capacity to rule at pleasure and without constraint. I think there needs to be a 4th branch of government, a sovereign council, tasked especially to oversee at least all administrative aspects associated with exercise of the constitutive power—the foremost defining power of sovereignty.

It has been a mistake to leave oversight of elections—which unequivocally belong to the People and not to the government—in the hands of office holders who may choose to disregard their oaths of loyalty to the People. Those office holders are always in danger of all-but-insuperable conflicts of interest, between their personal ambitions, and the oaths they swore which might require them to set personal ambitions aside, or surrender them altogether.

Today's breakdown in constitutional efficiency speaks eloquently of the need for the People themselves to correct the mistake they made so long ago, when they left an active voice for themselves out of the institutional structure of their government. They trusted personal fealty of oath takers in government to do a job which experience now proves must be taken out of the hands of government office holders.

An amendment appears to be the only route to a solution. Anxiety whether that will be prevented before it can happen—by a further unraveling in the defective structure now so beleaguered—is one all Americans must either suffer, or try to organize and contrive a solution for in advance of happenstance.

Until that happens, faithful and especially vigorous service to the oaths already taken by today's office holders may be the only way to prevent an untimely end to American constitutionalism. Americans who want to see this system of government continue must look especially to the Justice Department to take energetic action against oath breakers. And insofar as possible, to put questions of enforcement in the hands of jurors, and not in the hands of office-holding judges.

And should all 330 million Americans serve on this council? Or should, perhaps, we hold periodic contests where we select a subset of those 330 million people to do so, in a representative capacity?

Hmm… but then I guess we need a sovereign sovereign council to administer and oversee those contests, since office holders can't be trusted to do it. Should all 330 million Americans serve on that body? Or should we hold periodic contests where we select a subset of those 330 million people to do so, in a representative capacity?

How about that? Turtles all the way down!

That's an excellent comment and provides a lot to think about. I remain skeptical that any new branch could long avoid the same problems it is designed to address. I'm in the camp that says that enforcement is already in the hands of jurors -- the electorate whose verdict decides the election. If the people want Trump, then that's who they get. High priests divining intent should not get to control who goes on the ballot.

Your 4th branch sounds like the executive again, except one where Marbury v Madison turned out the other way.

Would an equivalent amendment be one that overturned Marbury by taking executive orders out of the jurisdiction of the courts?

That sounds pretty stupid IMO. In other words...

Why can't the Supreme Court properly address it?

Randal, the Supreme Court, a body composed of appointed members who serve for life, without legitimate power to exercise the constitutive prerogative and power, is especially unsuited to the need a sovereign council would properly serve. The Supreme Court cannot at the same time serve faithfully the sovereign People, and rival them in the exercise of their constitutive power.

A signature defect of decapitated constitutionalism is that it serves up such paradoxes and contradictions routinely. For instance, how can it be that government is at once the principal threat to individual rights, and also relied upon as their only efficacious defender?

That said, it is fair to ask for specifics about how to organize such a body. To raise that question and see what others might say was my main reason to comment above.

To kick off discussion, my own suggestions would (tentatively) include rules to disqualify sovereign council participants for life from any elective office, and probably to term-limit them to fairly short service. I might also suggest service on a parliamentary basis, instead of for set terms of office. I might even consider choosing members by lot, instead of by election or conventional appointments. Or by a mixed system, where senior leaders are elected on a national basis, but the vast majority are chosen at random. Possibly, all should serve without pay.

My suggestion for an amendment would limit sovereign council members to jurisdiction over issues of 3 kinds:

1. The proper exercise of the constitutive power, including direct oversight of all elections, impeachments and trials of impeachments, and disqualifications from office. That power of constitutive oversight would be continuous. It would extend to the entire government, including members of the courts, to solve the problem of faithless, politicized, and corrupt judges.

2. Punishment of oath-breaking, with special vigilance against elected officials who practice conduct tending toward rivalry for the People's sovereignty—for instance, a President who refuses to cooperate in a peaceful transition of power.

3. A power to promulgate laws and practices nationwide to maximize voter participation, and another power to overturn laws and practices, such as gerrymandering, designed to empower office-holder agency to affect election outcomes.

I offer those suggestions not because I suppose I have invented a perfect scheme—maybe not even a meritorious one—but just to break the ice on thinking specifically about an important class of problems which goes chronically unaddressed. If you wanted to solve problems like those I mentioned above, what methods would you suggest?

The obvious problem is that such a body is totally unconstrained. I would expect it to become the de facto electoral college and maker of all appointments. And that's best-case. It would probably also become the de facto center of power with its unconstrained threat of "punishment" against any government official.

Randal, and here I thought the Constitution announced in its first three words the jointly sovereign People as the de facto center of power in the United States. I take it you disapprove of that? If so, that puts you very much at odds with the founders.

Of course, you are in plentiful company. But have you noticed how many Americans fear that America's current distorted and paradoxical notion of constitutionalism is on the verge of foundering? What do you make of that? Are they wrong to be concerned?

I think that yes, the concern is overblown because it generates viewers, listeners, clicks, donations and votes.

Hence, checks and balances, and the Second Amendment.

Your notions don't address this paradox, they just shift it from "the government" to "the sovereign people."

"when they failed to institutionalize that sovereignty as an enduring institutional power at the top of their constitutional structure. "

Finally, you admit the flaw in your fetishistic concept of American democracy. The Framers did not fail, because your illusory sovereign would and could only have been a tyrannt.

Your imagined "popular sovereign" embodies all the clowns who inspired and participated in the January 6 riot and assault on the Capitol.

Nico, every sovereign is in principle a tyrant. That is what sovereignty means—the power to act at pleasure, without constraint. The genius announced by the invention of American popular sovereignty was the insight it embodied to better align the pleasure of the sovereign with the needs, interests, and preferences of the subjects. It was very clever to do that by making sovereign and subjects one and the same.

Although you seem not to have noticed it, I have confronted you with the question whether any modern nation state has ever existed, or can exist, without sovereignty. At the time of the founding, the better political theorists among the founders, including Franklin, Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, and James Wilson, all accepted a premise—set forth by Hobbes in Leviathan—that modern nation states require sovereignty. If you think otherwise, you ought to get to work and better Hobbes. Good luck.

So your position is the framers of 14A didn't want to exclude Confederates and oath-breakers from the presidency because it would've been too antidemocratic? But it wasn't too antidemocratic to disqualify them from every other elected federal and state elected office in the country. I'm not sure I buy it.

I buy it. You're not going to have a stable nation anyway if the person elected President is barred from the Presidency. If everyone had gotten together and decided yeah, we want a confederate President, then that sort of is what it is, oath-breaker or not.

The safeguards in place at the time were the electoral college and Congress's role validating and counting its votes. And all of those people are covered by 14A. (Except, perhaps, the VP, ironically.)

The electoral college was a safeguard in the sense of helping the country avoid electing a rebel on a whim or by accident. We've mostly abolished that guardrail. Trump may be our great punishment.

I believe that Amar's use of ad hominem to be much more uninteresting and less worth his audience's time than a clear explanation of his views on the issues would be.

Overall, Amar is an excellent constitutional scholar. This sort of ad hominem though is definitely not his finest moment. Even if it is not desperate, it LOOKS desperate. If someone's arguments are really not worth addressing, how about just don't address the arguments rather than engage in ad hominem rather than substance to dismiss them?

I think he’s allowed to loosen his tie, put his feet on the desk and go a little off piste on his own podcast. It's not like it's a SCOTUS brief.

I agree with Lee here. One of the asymmetries in our modern discourse is that we insist those who *actually* study subjects or *know* facts must moderate their language and gently guide an honest reader to the enlightened path.

Meanwhile, the demagogues malign anyone with actual expertise because the intelligentsia are always among the first targets of autocracy (and often revolution).

I value proper civil discourse based on knowledge. But the media no longer values it enough to forego reporting sensational lunacy and personal attacks. We are in an age of debate by public harangue, where experts can no longer take every podium hobbled.

I get the tension. But if everyone in the debate devolves to the same level, particularly via the "I hit him back first" arms race, where do we end up?

Yeah, he's allowed to.

But that rather than arguments makes his podcast boring shit-flinging rather than interesting discussion of issues.

Today is only Thursday. What Section 3 shoe will drop next? We have been to this rodeo before. People who have disagreed with us have later walked back their comments in one way or another. This happened on several occasions.

Sweaty.

Getting all worked up about definitions (or arguments about definitions) is even more pointless than usual when there is no application to be made. Trump is not going to be excluded.

Even if the genesis story of these terms has clear definitions, it's all pretty contrived stuff regardless. The categories involved are all constructed, and probably constructed insufficiently, or else "who was an officer" would be obviously tautological and not in need of lengthy interpretation or academic positions.

It's like that original planet of the apes movie where the apes were arguing about the sacred scrolls, or those episodes of south park where otters were arguing about the true definition of atheism.

If one wants to run on that sort of treadmill, maybe do it while running on an actual treadmill. At least some exercise will be had.

Intellectual exercise is being had and that is useful.

Debate on topics like this, while likely to remain just academic debates, reduce the chances of, for example, partisan misguided SOSs from deciding to actually pull the trigger on the anti-democratic action of excluding a presidential candidate from the ballot based on their personal views. This avoids the spectacle of a ridiculous, and ultimately unsuccessful for the SOSs, court battle. Such a court battle would amplify the “the Supreme Court bench is controlled by partisan hacks” meme – even when the decision would likely be 9-0 against the SOSs (those making such claims rarely look at the arguments closely).

The ballot exclusion theory is rather like the “trillion dollar coin” (although, now, this would perhaps be the “ten-trillion dollar” coin) theory. Something to be discussed and, by so discussing, making it clear to the proponents that their gambit to sidestep logic and the law would end up with them looking like zeros rather than heroes.

I think that, if Tillman seriously cares about civility in intellectual discourse, he has aligned himself with the wrong co-author.

This whole Section 3 debate is just another law school-centric tempest-in-a-teapot. The arguments being made in court are being tossed, Secretaries of State are not taking it particularly seriously, and it's only sort of pinging on op-ed pages. That legal "scholars" feel the need to get so deep into it that they're issuing catty rejoinders to oblique remarks and "take sides" in the debate just shows how out of touch they are, both with modern American legal issues and the practice of law.

This whole issue merited a brief, "Hm, isn't this interesting" post from Will. We don't need an "Akhil Amar is a poopyhead" series of exchanges.

It just hasn't heated up yet; The only people litigating it now are the people who actually want the question resolved, and aren't terribly determined that it be resolved in a particular way.

As you get closer to the election, you'll see lawfare from people who just see it as a club to hit Trump with, and want to wait until it's too late for any real possibility of it being resolved in Trump's favor to do him any good. People who are looking to do things like keep Trump off the ballot in a swing state until it's too late to reprint the ballots.

Fuck off, Brett. You have a "tails I win, heads you lose" conspiracy theory for every real-life event, and you don't need to repeat it every goddamn time someone comments on the subject. In the real world, this is a go-nowhere issue that will die out, just like any questions about Obama's citizenship or Hillary's ability to run for president (i.e., as a woman).

I suppose we'll see. I don't expect it to die out, but maybe you're right.

I am curious Brett, can you think of anything happening in the world that isn't a conspiracy against you in some way?

99.999999% of everything occurring just on Earth isn't a conspiracy against me. 0% of everything off Earth.

So a few hundred people are conspiring against you, roughly everyone you've ever become acquainted with?

Why do you think it's specifically against me?

I mean, take illegal immigration, for instance: Yeah, I think under-enforcement of immigration laws is deliberate, so I guess you can call that a "conspiracy", (Though that term is over-used for things that are happening right out in the open.) but it's hardly hurting ME, I'm a professional engineer, not a lot of those walking over the border with Mexico. Illegal immigration isn't hurting ME, it's hurting the unskilled poor whose wages it drives down.

So, just because I notice that something is deliberate doesn't mean I'm talking about a conspiracy against myself. Noticing that people are out to get somebody else isn't paranoia, you know.

You realize Biden just got slapped by the courts for over-enforcing immigration law, right?

But anyway no, that's not a conspiracy theory, that's just being ill-informed and wrong.

It's only a conspiracy theory once you get into making up people's motivations. That's where it's all about you. For example... Democrats are under-enforcing immigration law in order to dilute Republican votes is a conspiracy theory against Brett.

Amar is a brilliant scholar, but, as I've seen in person, he can be a real ass to people he disagrees with. Like it or not, he has no problem telling someone--even to their face--that he thinks they're unserious, stupid, etc.

And, in this instance, he also happens to be correct. The president and vice-president are clearly officers of the United States. So are judges and Justices. It's frankly absurd to say they aren't. Members of Congress and Pres/VP electors are not, which is why they were specified in Section 3. I mean, just use a modicum of common sense. The ratifiers of the 14th Amendment exempted out the most powerful federal official from disqualification? That's absurd.

All that said, I don't think Trump is automatically disqualified from office again. Assuming he engaged in rebellion or insurrection or gave aid or comfort to our enemies, and assuming Section 3 would otherwise be self-executing, Congress has the ability to enforce that section by appropriate legislation.

And, sure enough, it did so by passing 18 U.S.C sec. 2383, which criminalizes insurrection, rebellion, and giving aid or comfort thereto, and also includes within its punishment disqualification from federal office. (Theoretically, inability to hold state office is still self-executing since it is not part of sec. 2383's punishment.) Once Congress passed that law, it became the operative method by which someone becomes disqualified. And since Trump hasn't been convicted under that statute, he's not disqualified.

This is the way. Here's hoping the recent rash of ivory tower navel gazing that seeks to too-cleverly manipulate its way around this uncomplicated and straightforward reality will ultimately prove to be no more than a waste of their endowments and our time.

I'm not so sure... do you think 2383 takes away the ability of Congress to remove the disqualification? Normally Congress can't remove criminal penalties from an individual, that's a Presidential pardon power.

And on the other hand, can 2383 really disable someone from running for President? I don't think Congress can do that. The crime defined in 2383 is much broader than the disqualification condition of Section 3, meaning it's very possible to be convicted under 2383 in a situation where Section 3 doesn't apply. I think such a person could still be elected President.

I see how it's tempting to be like... it all works out somehow! But to me it looks like just a bunch of problems. 2383 is a poor match for Section 3, and since it doesn't claim to be a 14th Amendment implementing statute, I don't see any reason to take it as one.

"Normally Congress can’t remove criminal penalties from an individual, that’s a Presidential pardon power."

But Section 3 gives Congress that power in that limited context. Remember, Andrew Johnson was president when the 14th Amendment was proposed and ratified, and the Reconstruction Congress didn't trust him, to put it mildly.

"[C]an 2383 really disable someone from running for President?"

Running for president? Probably not. Serving as president? I think so.

"The crime defined in 2383 is much broader than the disqualification condition of Section 3, meaning it’s very possible to be convicted under 2383 in a situation where Section 3 doesn’t apply."

If someone is convicted under sec. 2383 for conduct that doesn't meet constitutional provisions (e.g., "assists" an insurrection), yes, you're probably right that he can't be disqualified under Section 3. In that case, the disqualification punishment is largely irrelevant, I'd say, since Congress can't add to constitutional qualifications. But if someone is, say, convicted of *engaging* in insurrection under sec. 2383, then I think they are disqualified.

"2383 is a poor match for Section 3, and since it doesn’t claim to be a 14th Amendment implementing statute, I don’t see any reason to take it as one."

Not sure how it's a poor match. It uses almost the exact same language, has a disqualification provision, and was legislation passed by Congress. Without saying, "This Act implements Section 3 of the 14th Amendment," I don't see how it could be more on point.

Well, look how convoluted it makes things, just from the cursory analysis you and I have done.

1. If you never took an oath and get convicted of engaging in an insurrection, you can be President.

2. If you never took an oath and get convicted of engaging in an insurrection, you can't be Secretary of State, and you can't have your disability removed by Congress.

3. If you have taken an oath and get convicted of engaging in an insurrection, you can't be Secretary of State, but voila, you can have your disability removed by Congress. (I guess?)

4. If you have taken an oath and get convicted of inciting an insurrection, you can't be Secretary of State, and once again you can't have your disability removed by Congress.

5. If you have taken an oath and get convicted of inciting an insurrection, you can be President.

This just doesn't have the sense of a typical implementing statute which explicitly works to flesh out the details that the Constitution glosses over. 2383 doesn't fill in any details, it's just a simple criminal law. It's wildly over- and under-inclusive compared to Section 3, so really all it does if you try to take it as an implementing statute is create this hodge-podge of conflicts.

Hey, an honorary navel-gazer! Maybe it's time for a career change.

Hm. That's fine, but you haven't even gotten as far as navel-gazing, your still stuck at "I like this idea! It fits my priors and my politics!" so I'm ahead so far.

At least find some neutral and / or respectable commentary making your case to point to. As far as I can tell, 2383 remains just a fringe theory relegated to VC comment threads.

Yeah, ok. If the ivory tower doesn't care to treat the actual statute on the books vis-a-vis insurrection as having any relevance to determining when someone has engaged in insurrection, that says a lot more about them than it does me.

True! It says almost nothing about you.

Maybe the argument is "unserious and stupid" as you say. But this

"I mean, just use a modicum of common sense. The ratifiers of the 14th Amendment exempted out the most powerful federal official from disqualification? That’s absurd."

doesn't strike me as a compelling basis for concluding so. It might make common sense that some of the ratifiers - after having deprived the southern states of representation for purposes of "ratifying" this particular amendment - would have liked to exclude persons from the Presidency even more than they wanted to exclude them from other positions. But that doesn't necessarily mean they did so, or that all of the ratifiers or their constituents would agree with it, or that this was the particular political solution intended.

"The president and vice-president are clearly officers of the United States"

Can you show me the work on that?

Because it's not remotely clear to me that the term of art "Officers of the United States" includes the Chief Executive (or vice-Chief).

("Officer" means "one who holds an office", as well as, with long usage predating the Republic, "one who has a position of power via appointment".

The question for term one is "is the Presidency an Office in that sense?", which is ... not an obvious slam dunk on its face, though maybe it is!

And the second one, well, obviously can't include the President, since he's the one that DOES or confirms the appointments, depending on the office - like every military officer commission.)

I have no partisan or even notional dog in this fight, I just don't think it's "clearly" the case that the President is an Officer.

(I agree completely that to DQ Trump he'd need to be convicted under 18 USC 2383 in any case.

Which would lead to the Supreme Court eventually deciding whether or not the President is an Officer or not.)

Re the president being an officer, I would refer you to Amar's work on this. Even though he can be an ass, his work is solid. I wouldn't do it justice here.

Perhaps you could show a little of your work, specifically why the 14A framers would've been okay with Confederates and oath breakers as President or Vice-President.

I have great respect for Professor Amar, but the notion that Professor Tillman is not a careful, thorough and esteemed scholar is itself laughable.

Did Prof. Amar ever say that about Prof. Tillman? He certainly shows no respect for Tillman's position on this subject.

I don't know about Amar, but other scholars praise him.

Larry Solum: "LIke this Baude and Paulsen article, this [by Tillman]reply is highly recommended."

Professor Robert Blomquist: (commenting on several Tillman articles): "Constitutional gamers of all stripes should be thankful for the brilliant and bracing thoughts of Seth Barrett Tillman."

Jed Shugerman, John Mikhail, Jack Rakove, Gautham Rao,

Simon Stern (in an apology to Tillman): "We regret these errors and extend our apologies to Professor Tillman, whose diligent research we admire. We appreciate his long-standing position on how to interpret the Constitution’s reference to 'Office of Profit or Trust under [the United States],' regardless of who is holding the office of President, and we respect his commitment and creativity in pursuing that interpretation."

And there are others.

Mr. Mukasey is, I believe, a director of the Federalist Society and a reliable promoter of Republican-conservative positions (to the point of not only accepting torture, as I recall, but also claiming it worked).

Mr. Calabresi is, I believe, a director of the Federalist Society and a reliable promoter of Republican-conservative positions (but not, so far as I recall and to his credit, an advocate or apologist for torturers).

Beyond poking at Prof. Amar, the Volokh Conspiracy seems to be addressing this issue from perspectives ranging from hard right to harder right.

And in what respect do you denigrate Seth Barrett Tillman?

Is it denigration to observe that he readily falls into the hard-right classification with Baude, Blackman, Calabresi, Mukasey, Paulsen, the Volokh Conspirators, etc.?

I think he goes where the evidence leads him—and is known for that.

Reality has a conservative bias.

The evidence, as divined by that guy, always leads to Clingerville.

Hard to believe Harvard and Yale aren't competing for his services.

"Theoretically, inability to hold state office is still self-executing since it is not part of sec. 2383’s punishment."

No, disqualification from state office would be a matter of state law.

The problem there is that you'd be trusting the states to govern themselves on that score, which would be weird since it was those very state actors that this provision was aimed at. Maybe you're right. But it seems completely at odds with the historical context.

While "not an insurrectionist after taking a relevant oath" is a qualification for becoming president, it should not bar a candidate from the ballot in the way that being too young, not a natural born citizen, or not having lived in the United States for 14 years. Failing those other requirements are things that Congress can ignore but not remove, while 14th amendment disqualification can be removed. The answer could be different for a state office or a member of Congress chosen by only one state, since the original point was to stop Confederate states from putting oath-breaking Confederates into office. But the entire country chooses a president (directly or indirectly). Congress has plenty of time to remove disqualification before an insurrectionist president takes office, and if they don't, it's no different than if they refused to recognize the relevant electoral votes under the Electoral Count Act.

Disqualification through what mechanism? If via an actual conviction under 18 USC 2383 as discussed above, I agree. If via anything more subjective, this would seem just to replace the self-execution silliness with equally unjustifiable burden flipping.

Except that the Constitution explicitly gives Congress the authority to remove (or not remove) the section 3 disqualification, but not recognizing electoral votes is a dubious power Congress granted itself.

Seth Tillman doesn't strike me as a kook. He seems like an intelligent and interesting legal scholar. But the Tillman-Blackman theory of federal offices and officers increasingly strikes me as kooky.

It reminds me of the John Eastman theory that Wong Kim Ark was wrongly decided. Every so often I would see some piece by Eastman opining on an issue or on someone's eligibility to be president, and I would say "that was interesting, it seems sincere, and it is consistent with his past positions, but ultimately it is just one more application of the same underlying theory that is unpersuasive, out of the mainstream, and never going to be adopted by any court."

I am a bit confused. Not being a lawyer, before section 3 of the 14th amendment be 'active', should there at least there be a criminal conviction for the referenced 'crimes'? And if that is to be the case, where is Trump's protections of the 5th amendment? Less we forget.

What goes around, comes around.

Section 3 doesn’t reference any crimes.

Not being allowed to be President isn't a deprivation of life, liberty, or property.

That's just total bullshit.

Insurrection is a crime.

Rebellion is a crime.

Giving aid and comfort to the enemy is a crime.

And all three, by law, result in disqualification to hold office: They are, in fact, Section 3's enabling legislation!

I'll agree with that last point: The question here isn't Trump's rights, it's the rights of the voters some people are trying to deprive of a choice.

Rape is a crime, but you can be a rapist without being a convicted rapist.

Anyway, that's a long and boring debate we've already had and is irrelevant anyway.

What enabling legislation are you thinking of for giving aid and comfort to the enemy?

More magic words.

Yes, you think the word "insurrection" is so magical, it has legal effect without the necessity of a trial and conviction. That's your magical thinking.

All words have legal effect without the necessity of trial and conviction, with the possible exception of "sentence."

Your head will collapse, and there's nothing in it

And you'll ask yourself

Where is my mind?

Where is my mind?

You think any qualifying act must be a crime called insurrection.

Actually things can be insurrection without the term itself being invoked. Because there is no magic words.

You think they described conduct that was actually existing crimes, without meaning the crimes. Why?

Because it's the only way to justify the nearly absent due process you want to get by with, that's why.

I think it doesn’t need to be a crime, your due process standard is made up and doesn’t come from text or original intent or anything else.

I think one example of your overdetermined outcome is you keep leaning on Congress needing to use the magic word.

Your use of "magic words" is a but slippery debating trick otherwise know as the legal theory of humpty-dumptyism.

What? The 'you must say insurrection' is a bad argument made by Brett, additionally to his also made up 'it has to be a crime' requirement.

No fallacy involved - Brett is doing a thing that I did in the early years of law school - to insist that a particular term must be exactly invoked or else the law does not operate.

Laws, because they function in the real world, do not require magic words to work; something functionally appropriate is all that's needed.

Because the entire point of the 14th amendment was to disqualify oodles of southerners from office, people who were not charged with, and who nobody thought were ever going to be charged with, any crimes.

So... you're saying a state can block everyone of a certain race from, say, running for governor, without there being a due process issue with that?

Yep.

But there would be an equal protection issue.

Congrats on the paper and all the attention it's getting!

Of course Seth and Josh don’t object to Amar’s language. Heaven forfend! They’re not saying he’s wrong. Indeed they applaud his willingness to be direct and clear and to embrace being controversial!

I’m impressed they can breath under the weight of all that smug apophasis.

See also: “The Limited Sweep and Ineffectual Force of False Analogies: A Brief Reply to Baude and Paulsen”

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4564998

Wow, Akhil sounds so smug and clubby in that podcast -- what an asshole -- instead of engaging with the substance of Tillman and Blackman's paper, he just writes off their work because of their academic pedigree; Amar can go fuck off!