The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Private Employers May Not Fire Employees for Writing to the Legislature, Tennessee Court Holds

BlueCross BlueShield allegedly fired an employee for "email[ing] Tennessee state legislators with her concerns and grievances regarding vaccine mandates."

In Smith v. BlueCross BlueShield of Tenn., decided today by the Court of Appeals of Tennessee (in an opinion by Chief Judge Michael Swiney, joined by Judges John McClarty and Kristi Davis), Smith alleged that BlueCross had wrongly fired her for, among other things, "email[ing] Tennessee state legislators with her concerns and grievances regarding vaccine mandates." The court concluded that this stated a claim under Tennessee law:

This case implicates the doctrine of employment-at-will. Under this doctrine, "employment for an indefinite period of time may be terminated by either the employer or the employee at any time, for any reason, or for no reason at all." It is undisputed that Smith was an at-will employee of BlueCross when she was fired. However, there are certain exceptions to the doctrine, and an employee may bring a retaliatory discharge action if she is fired in violation of public policy. Here, Smith alleged just that.

Our Supreme Court set out the elements of a common law retaliatory discharge claim thusly:

In Tennessee, the elements of a typical common-law retaliatory discharge claim are as follows: (1) that an employment-at-will relationship existed; (2) that the employee was discharged, (3) that the reason for the discharge was that the employee attempted to exercise a statutory or constitutional right, or for any other reason which violates a clear public policy evidenced by an unambiguous constitutional, statutory, or regulatory provision; and (4) that a substantial factor in the employer's decision to discharge the employee was the employee's exercise of protected rights or compliance with clear public policy.

"[T]he exception cannot be permitted to consume or eliminate the general rule." To be liable, the employer must have violated a clear public policy, which usually is "evidenced by an unambiguous constitutional, statutory or regulatory provision." …

Article I, Section 23 of the Tennessee Constitution reads: "That the citizens have a right, in a peaceable manner, to assemble together for their common good, to instruct their representatives, and to apply to those invested with the powers of government for redress of grievances, or other proper purposes, by address or remonstrance." {[I]t is evident that [this] concerns the right to petition.}

"[T]he right of petition is … 'an ancient right' and 'the cornerstone of the Anglo-American constitutional system.'" "Parliament used the Petition of Right to 'gain popular rights from the king,' and the people eventually 'used petitioning as the means to secure their own rights against parliament.'" Indeed, "'[t]he development of petitioning is inextricably linked to the emergence of popular sovereignty.'"

We also note the case of Little v. Eastgate of Jackson, LLC (Tenn. Ct. App. 2007), a case in which an at-will employee was fired who had, while on the clock, rescued someone who was being assaulted across the street…. We recognized "that, in limited circumstances, certain well-defined, unambiguous principles of public policy confer upon employees implicit rights which must not be circumscribed or chilled by the potential of termination." … [H]aving considered certain Tennessee statutes dealing with various exigent circumstances, we found that "[t]hese statutes evidence the unambiguous legislative intent to pronounce the Tennessee public policy of encouraging citizens to rescue a person reasonably believed to be in imminent danger of death or serious bodily harm, and to protect a citizen who undertakes such heroic action from negative repercussions." In concluding, we "agree[d] with the trial court's recognition of a clearly-mandated public policy in favor of encouraging citizens to rescue others reasonably believed to be in imminent danger of death or serious bodily harm, and find that this public policy may be the basis for an exception to the at-will employment doctrine in Tennessee." …

[P]ublic policy exceptions are to be carefully drawn so as not to eliminate the general rule. For one example, BlueCross cites the interference in the employer-employee relationship that would result if the constitutional right of free speech were found to be a public policy exception to at-will employment. In such a scenario, an at-will employee could publicly denigrate her employer all she wished and her employer would face liability for firing her on that basis. Of course, Tennessee law does not restrict an employer in that way.

In the appeal at bar, however, we are addressing a right of a somewhat different character. Constitutional free speech restrictions are directed at the government. That is, the government may not enact laws abridging free speech. The right to petition, while no more or less important than the right to free speech, makes sense only as an affirmative undertaking by a citizen. The State of Tennessee would not need to pass a law to restrict its ability to hear petitions if it were inclined to do so. It could just decline to consider them. In any event, it would not need to ban them.

It therefore stands to reason that clear public policy is violated when an entity, even a private entity, tries to block a citizen from petitioning the government. Otherwise, the right to petition—the "'cornerstone of the Anglo-American constitutional system'"—is hollow. While under the doctrine of employment-at-will, employers may fire at-will employees for almost any reason or none, the doctrine is not absolute. Firing an at-will employee merely for writing to the Tennessee General Assembly is a bridge too far. It unduly interferes with the employee as citizen. Unlike other examples of constitutional provisions which as BlueCross rightly points out are not extended to private employers, the right to petition goes to a cornerstone of how employees, as citizens, can reach their government. While an at-will employee may not reasonably expect the full panoply of constitutional rights from a private employer, she must have recourse to the very people who make law.

At oral arguments, counsel for BlueCross stated that Smith was fired for the substance of what she wrote to the General Assembly, as opposed to the fact that she wrote. However, this statement by counsel is not dispositive of the issue before us, which is whether there is a public policy exception to employment-at-will based on the right to petition found in the Tennessee Constitution. This case was decided below on a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim. We are limited to the facts alleged by Smith. In her complaint, Smith alleged that she emailed the General Assembly to convey "her concerns and grievances regarding vaccine mandates" and "to seek legislative protection for her individual liberties and rights relating to vaccine mandates." She alleged that she was fired for having written to members of the General Assembly. In its brief, BlueCross says that Smith, in her emails, disseminated misinformation; insulted her employer; divulged confidential BlueCross business information; and made untruthful statements. None of those facts are alleged in Smith's complaint. {BlueCross could, of course, potentially substantiate its characterizations of Smith's actions through a properly-supported motion for summary judgment or at trial.} …

Moreover, adopting BlueCross's position would mean that an employer could fire an at-will employee for any communication to the legislature, whatever the content. While Smith's grievances happened to concern vaccine mandates, any number of scenarios can be visualized. An at-will employee could write the General Assembly about workplace safety issues, wages, or other labor conditions. An at-will employee could write the General Assembly on a matter totally unrelated to her employment. Under BlueCross's stance, no matter the scenario, there is no public policy protection from termination for an at-will employee for exercising her constitutional right to petition. That is contrary to the unambiguous public policy expressed in Article I, Section 23 of the Tennessee Constitution.

We emphasize, however, that the doctrine of employment-at-will remains firmly established in this state, and this matter concerns only a very narrow area, the right to petition. In the majority of circumstances, employers in Tennessee can terminate at-will employees for good reasons, bad reasons, or no reasons at all, and face no liability for retaliatory discharge. We also take no position on the underlying merits of Smith's grievances.

Finally, BlueCross warns of harmful societal consequences stemming from a public policy exception for the right to petition. BlueCross argues that an employee could simply tag in a legislator on an email or letter to invoke the protection of the right to petition, and thereby make a mockery of the exception. That concern is not well-founded.

An at-will employee who, for instance, writes a scathing letter to the editor about her employer and merely tags in a legislator as a token bid toward that end does not enjoy the protection of the public policy exception for the right to petition. The public policy expressed in Article 1, Section 23 of the Tennessee Constitution extends only to communications to the government. If an at-will employee addresses non-governmental people or entities, she cannot benefit from the public policy exception for the right to petition. Notwithstanding this, BlueCross argues that recognizing a public policy exception for the right to petition will create a "flood of litigation." Respectfully, this is the least persuasive of BlueCross's arguments. It is exceedingly unlikely that courthouses in Tennessee will overflow with litigants suing their former employers for firing them for writing to the General Assembly. Such an effusion of civic-mindedness, were it to occur, would in any event be grounds for commendation, not scorn.

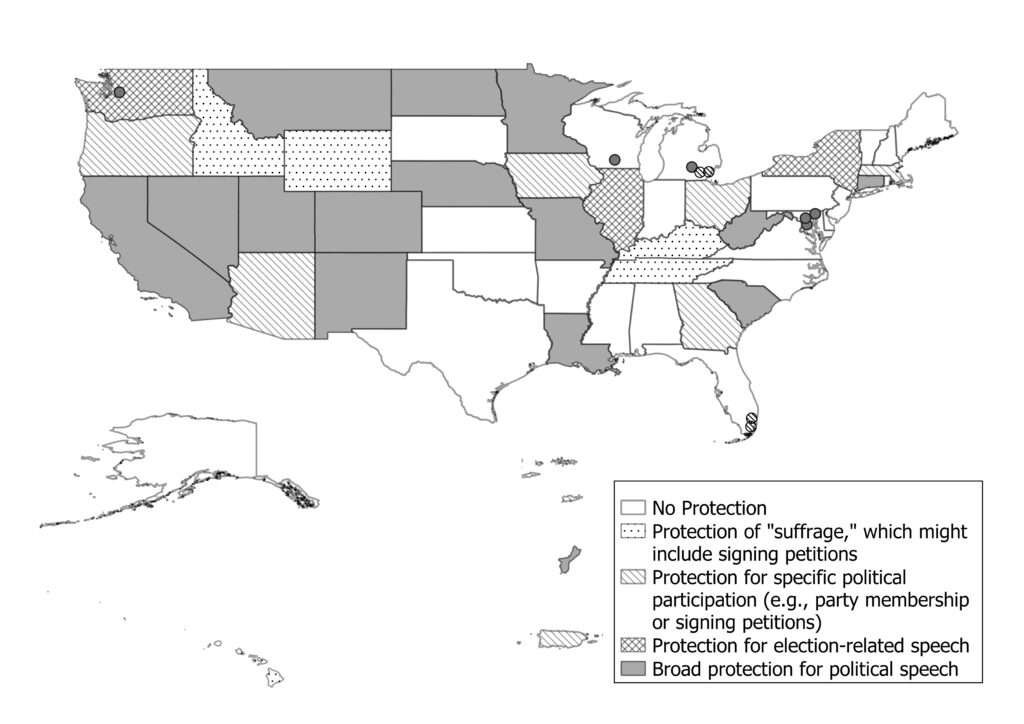

Note that many states have state statutes that bar private employers from firing employees based on various forms of speech and political activity.

Here, though (unlike with the statutes noted on the map above), the court concluded that private employers are limited as a matter of state common law, even in the absence of statute, in their ability to fire an employee based on the employee's speech to legislators. For narrower versions of this rule, apparently limited to testimony before legislators, see Donohue v. Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. (D.S.D. 2023), Carl v. Children's Hospital (D.C. 1997), and Bishop v. Fed. Intermediate Credit Bank of Wichita (10th Cir. 1990).

Congratulations to Stephen S. Duggins and Colson Duggins, who represent Smith.

Show Comments (14)