The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Does Anyone Have Standing to Bring a Lawsuit Against Biden's Student Loan Debt Cancellation Policy?

The likely answer is "yes." There are three types of potential litigants who probably qualify.

In previous posts, I criticized both the Biden administration's legal rationale for the president's massive student loan debt cancellation policy and a possible alternative justification for it. But many experts think these issues will never get their day in court, because no one will have standing to file a lawsuit challenging debt cancellation. Perhaps the administration sees this procedural issue as their ace in the hole: it doesn't matter if the legal justification for your program is weak if no one can get into court to challenge it!

The problem of standing is a genuine challenge for opponents of the debt cancellation policy. But it need not be an insuperable one. There are at least three types of litigants who can plausibly get standing: one or both houses of Congress, student loan servicers, and colleges that do not accept federally backed student loans, but compete with those that do.

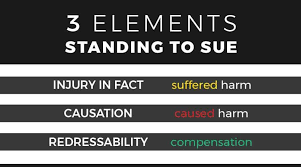

Under current Supreme Court precedent, plaintiffs have to meet three requirements to get standing to file a lawsuit in federal court: They must 1) have suffered an "injury in fact," 2) the injury in question must be caused by the allegedly illegal conduct they are challenging, and 3) a court decision should be able to redress the injury.

In my view, the entire doctrine of standing is not a genuine constitutional requirement, and the Supreme Court should abolish it. But that's highly unlikely to happen. So, for present purposes, I will assume the validity of current precedent. Whether it's right or not, litigants will have to work within it.

The main potential stumbling block in this case is the requirement of "injury in fact." It may be difficult to prove that student loan cancellation injures anybody, in the sense required by Supreme Court precedent. Cancelling some of A's student loan debt doesn't necessarily injure B and C. The others may believe it is unfair they had to pay off all their loans themselves, while A doesn't. But, with rare exceptions, current precedent requires some sort of tangible injury. Unfairness, by itself, isn't enough.

It may be that taxpayers suffer a tangible injury, because loan forgiveness denies funds to the federal treasury, thereby forcing them to bear more of the burden of public expenditures. Any illegal expenditure of public funds necessarily diverts taxpayer resources away from duly authorized purposes. But the Supreme Court has long denied such taxpayer standing, in all but a few unusual circumstances, which aren't relevant here.

I think taxpayers should have broad standing to challenge any unconstitutional expenditure of public funds. But this is another issue on which the Supreme Court is unlikely to go my way, anytime soon.

But while taxpayers generally do not have standing to challenge illegal uses of public funds by the executive, the Senate and the House of Representatives do! The US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit so held in a 2020 case where the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives filed a lawsuit challenging Donald Trump's attempt to divert military funds to build his border wall (a case which has many parallels to the present situation). The decision was written by prominent conservative Judge David Sentelle, who reasoned as follows:

[T]he House is suing to remedy an institutional injury to its own institutional power to prevent the expenditure of funds not authorized. Taking the allegations of the complaint as true and assuming at this stage that the House is correct on the merits of its legal position, the House is individually and distinctly injured because the Executive Branch has allegedly cut the House out of its constitutionally indispensable legislative role. More specifically, by spending funds that the House refused to allow, the Executive Branch has defied an express constitutional prohibition that protects each congressional chamber's unilateral authority to prevent expenditures….

To put it simply, the Appropriations Clause [of Article I of the Constitution] requires two keys to unlock the Treasury, and the House holds one of those keys. The Executive Branch has, in a word, snatched the House's key out of its hands. That is the injury over which the House is suing…

To hold that the House is not injured or that courts cannot recognize that injury would rewrite the Appropriations Clause. That Clause has long been understood to check the power of the Executive Branch by allowing it to expend funds only as specifically authorized…

Sentelle's reasoning is compelling, and pretty obviously applies to Biden's loan forgiveness plan, no less than Trump's border wall diversion. Under this approach, either the House or the Senate would have standing to sue, even if the other house chose not to. The DC Circuit decision was later vacated by the Supreme Court when the case became moot, after Biden terminated Trump's efforts to divert the border wall funds. But the DC Circuit and other lower courts are likely to adopt its approach in any future case on the same issue.

Of course neither house is likely to sue so long as Democrats control both of them. But that could change after the November election, when Republicans could potentially retake one or both of them (the House far more likely than the Senate). If so, they could rely on the border wall precedent to get the standing they need for a lawsuit.

Unfortunately, the House or Senate would likely have to file as an institution in order to get standing. The Supreme Court has ruled that individual members of Congress lack standing to sue the executive over fiscal issues.

A second type of entity that could get standing to sue is student loan servicers. These firms collect student loan payments on behalf of the government, and the size of the fees they get depends in part on how much money is owed, whether the loan is delinquent, and how long the borrower takes to repay it. If loan forgiveness reduces delinquency rates, enables some borrowers to repay faster, or otherwise affects the amount servicing firms get paid, they pretty obviously suffer an injury in fact, and would have standing to sue. Fordham law Prof. Jed Shugerman has reached much the same conclusion.

It's possible loan servicers will be afraid to sue, because they don't want to antagonize the federal Department of Education. A good relationship with the feds may be necessary to ensure their continued profitability. But if any are willing to sue, standing shouldn't be much of a problem. And one plaintiff is enough to get the issue to court. Even if most loan servicers prefer to stay out of it, one may be willing to take the risk. Alternatively, they could band together and sue jointly, thereby making it harder for the Department of Education to retaliate against them (since the Department may be reluctant to cut them all off).

A final category of plaintiffs who could get standing is colleges that refuse federal funding (including federal student loans), but compete with those who accept it. These mostly conservative-leaning institutions reject federal funds because they do not want to be subject to the regulations that come with them. Examples include Grove City College, and Hillsdale College. For obvious reasons, loan cancellation makes colleges that accept federal student loans more competitive relative to those that do not. The latter become relatively cheaper alternatives for students.

Courts have long recognized "competitor standing" to sue to challenge policies that strengthen the competitive market position of the plaintiff's rivals. Perhaps the competitive injury here is small. Maybe only a few students are likely to forego attending Grove City College or Hillsdale as a result of Biden's actions. But even a small financial loss, such as nominal damages, is enough to qualify as an "injury in fact" under standing doctrine.

These three possibilities aren't necessarily exhaustive. They are just the ones that most readily occur to me, and I admit I am far from being an expert on student loans. There may be other types of litigants who can also get standing to challenge Biden's student debt cancellation plan. But these examples do suggest that standing need not be a show-stopper here. More likely than not, courts will eventually have to rule on the legal merits of the policy.

UPDATE: I have revised this point to note that the DC Circuit case was later vacated as moot.

Show Comments (57)