The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Slippery Slope June

How should we think about slippery slope arguments, whether they come from liberals or conservatives or libertarians or anyone else?

Some online discussions recently reminded me of The Mechanisms of the Slippery Slope, an article I published in 2003 in the Harvard Law Review. Slippery slope arguments are often made, quite categorically, as if saying "slippery slope" is enough to resolve an issue; but they are also often rejected, quite categorically, often with claims that they are outright fallacies. I think the matter is more complicated, in part because there are multiple mechanisms through which slippage can happen (and through which it can be resisted); and I thought I'd therefore serialize the article in some blog posts over the coming few weeks.

I think that might be particularly helpful now. The seemingly impending rejection of a constitutional right to abortion is likely to lead to many proposed restrictions in various states and in Congress. Many of the arguments about those restrictions will likely focus on the specific substance of the restrictions on their own terms—but many, especially ones that seem modest on their own, will lead to arguments that these are just the first steps down a slippery slope.

I expect we'll likewise see more such arguments with regard to proposed gun restrictions. And of course the arguments are commonly made with regard to new forms of surveillance, new forms of economic regulation, and indeed new forms of deregulation.

Slippery slope arguments aren't exclusive to liberals or conservatives, though different groups tend to deploy them as to different matters. Rather, they can be made with regard any sort of change, whether to the left, to the right, or elsewhere. My posts will use examples from a variety of areas, though chiefly as to abortion, free speech, guns, and privacy, which are areas I've focused on more; but my goal will be to analyze such arguments generally, and not call for any particular policy results.

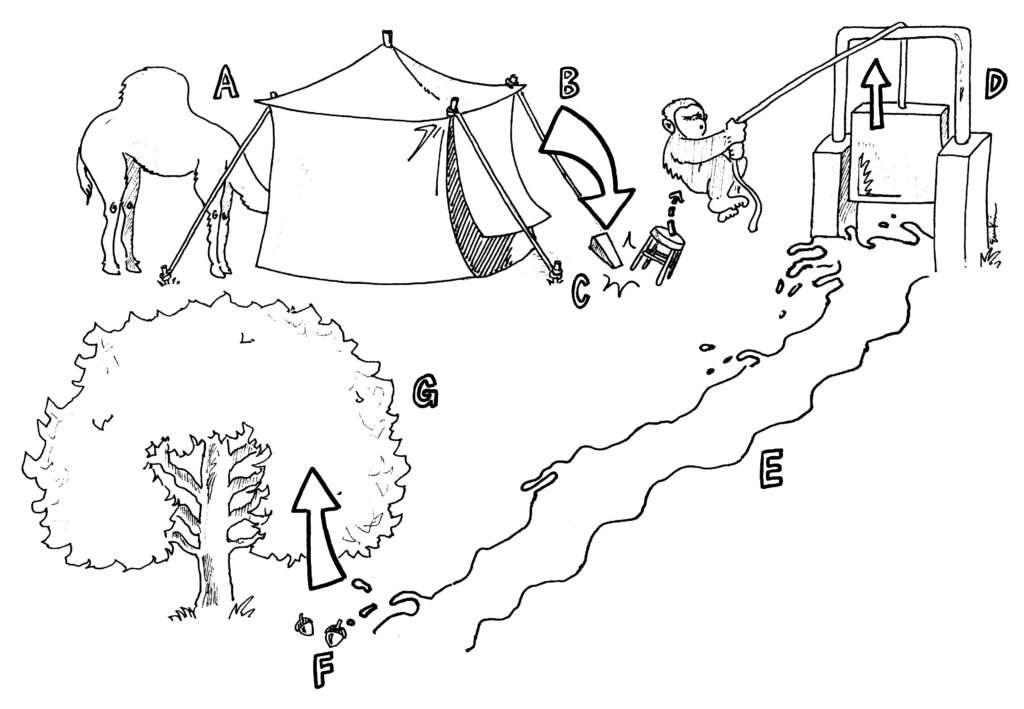

I will define slippery slopes broadly, to cover all situations where decision A, which you might find appealing (or at least not highly objectionable), ends up materially increasing the probability that others will bring about decision B, which you oppose. I recognize that there are many ways this could happen (hence the plural "Mechanisms"). But if you are faced with the pragmatic question "Does it make sense for me to support A, given that it might lead others to support B?," you should consider all the mechanisms through which A might lead to B, whether they are logical or psychological, judicial or legislative, gradual or sudden.

You should consider these mechanisms whether or not you think that A and B are on a continuum where B is in some sense more of A, a condition that would in any event be hard to define precisely. You should think about the entire range of possible ways that A can change the conditions—whether those conditions are public attitudes, political alignments, costs and benefits, or what have you—under which others will consider B.

Of course you shouldn't limit yourself to slippery slope questions: You should consider the preceding two questions (how good is A and how bad is B?). You should consider whether the refusal to enact A is likely to lead to bad consequences, perhaps including the very same decision B (for instance, if the refusal could yield a political backlash against what voters might perceive as the obstinacy of the anti-A forces). You should consider what the alternatives to A might be, and more factors still. But in this series of posts, I hope to focus in detail part of one part of the policy analysis, which has to do with the slippery slope concern.

My first substantive post will go up tomorrow, June 1, but I also plan on posting, about once a day, snippets from prominent people making such arguments in the past, as well as responding to such arguments. Naturally, by themselves those snippets won't tell you much, but I thought they'd be helpful and often entertaining illustrations, and will also remind us that the subject has been taken seriously for centuries, even millennia. I hope you folks find all this interesting.

UPDATE: I originally described decision A here as one you "might find appealing," but some readers took it to mean that it had to be one you did find appealing. I've since updated that to read, "might find appealing (or at least not highly objectionable)." My published article itself makes that clear, when it says near the beginning "You think A might be a fairly good idea on its own, or at least not a very bad one."

Show Comments (108)