The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

University Adjunct Prof Fired for Labeling Flyers About "Microaggressions" as "Garbage"

may have had his First Amendment rights violated, if the facts are as he alleges them to be, says a federal court.

From Hiers v. Board of Regents, released today by Judge Sean Jordan (N.D. Tex.):

Writing for himself and Justice Brandeis nearly a century ago, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes extolled what he viewed as a foundational tenet of freedom of expression in our country: "[I]f there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other it is the principle of free thought—not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate." Since that time, the Supreme Court has consistently recognized that the Founders "believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth."

This case implicates these bedrock constitutional principles protecting freedom of thought and expression. The setting is a public university, the University of North Texas ("UNT"), and the speaker is [an untenured] mathematics [adjunct] professor at that university, and a public employee, Nathaniel Hiers. Amidst a slew of constitutional claims asserted by Hiers following his departure from UNT, a single question is paramount: What can a public employee say, and what can he choose not to say, without fear of reprisal from his employer? …

On November 26, 2019—the same day that Hiers [a nontenured, adjunct professor,] stated his desire to teach a second class in the spring—the incident forming the basis of this lawsuit occurred. An anonymous person had placed in the mathematics faculty lounge a stack of flyers, each of which warned faculty against committing "microaggressions" on college campuses. The flyer defines microaggressions and provides examples of statements characterized as microaggressions that it suggests faculty should avoid using in the workplace. For instance, statements such as "I believe the most qualified person should get the job" and "America is the land of opportunity" are cited as microaggressions promoting the "[m]yth of [m]eritocracy."

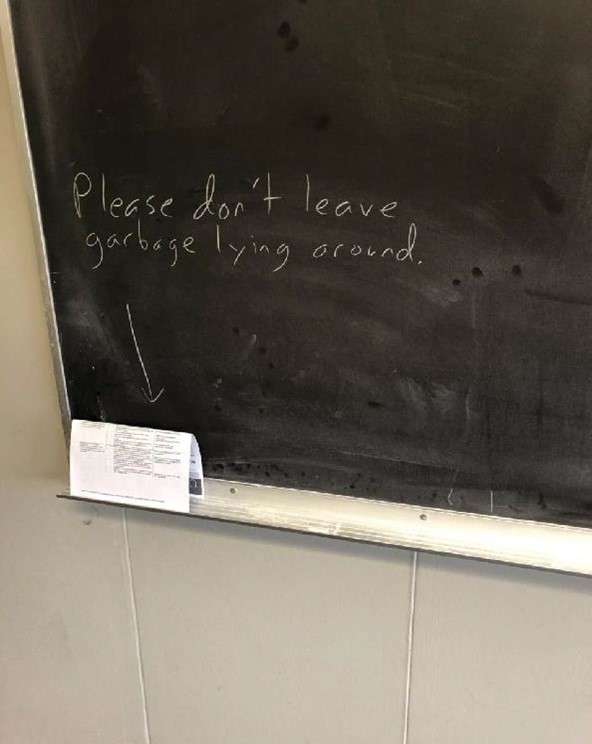

Upon seeing these flyers, Hiers—in what all parties agree was intended as a joke—picked up a stick of chalk, drew an arrow pointing to one of the flyers, and wrote the following message on a nearby chalkboard: "Please don't leave garbage lying around." …

Hiers' contract was not renewed as a result of this; his department chair, Ralf Schmidt, explained the decision this way:

Dear Nathaniel,

My decision not to continue your employment in the spring semester was based on your actions in the grad lounge on 11/26, and your subsequent response.

In our conversation you characterized the flyers that upset you as political statements. I looked at them in detail, and they are anything but. Every example of a microaggression listed there makes very much sense, and I am disappointed about your general dismissal of these issues and that you failed to put yourself in the shoes of people who are affected by such comments.

I also think that leaving behind a chalkboard message like you did is not a benign thing to do. Think about how people who see this might react. They don't know who wrote this; it might be a faculty member, grad student or anyone else. The implicit message is, "Don't you dare bringing [sic] up nonsense like microaggressions, or else." This is upsetting, and can even be perceived as threatening.

Finally, I was disappointed at your response during our conversation. Everyone makes mistakes, and I'm all for forgiveness if actions are followed by honest regret. But you very much defended your actions, and stated clearly that you are not interested in any kind of diversity training.

In my opinion, your actions and response are not compatible with the values of this department. So with regret I see no other choice than to not renew your employment. Please know it gives me no pleasure; in fact, we were counting on you, and it causes considerable difficulties to replace you as a teacher….

The court concluded that Hiers' First Amendment retaliation claim could go forward:

Public employees do not surrender all First Amendment rights because of their employment…. [W]hen citizens enter government service, they necessarily accept certain limits on their freedom of speech…. But if employee expression [that is not part of the employee's official duties] touches on a matter of public concern, the First Amendment prohibits the government from taking an adverse employment action against the employee for such expression without sufficient justification.

It is undisputed that Hiers suffered an adverse employment decision—termination—and his speech motivated the university officials' termination decision. That leaves two questions: First, was Hiers speaking on a matter of public concern? And if so, was Hiers's interest in doing so greater than the university's interest in promoting the efficiency of the public services it provides through its employees? The university officials do not address the second question, so the Court will focus its analysis on whether Hiers's speech touched on a matter of public concern….

Personal complaints and grievances about conditions of employment are not matters of public concern. Rather, speech addresses a matter of public concern when it relates "to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community." The lynchpin of the inquiry, then, is the extent to which the speech advances an idea that transcends personal interest or conveys a message that impacts our social or political lives.

Here, Hiers's critique of the flyer on microaggressions transcended personal interest and touched on a topic that impacts citizens' social and political lives. His speech did not address a personal complaint or grievance about his employment. The point of his speech was to convey a message about the concept of microaggressions, a hot button issue related to the ongoing struggle over the social control of language in our nation and, particularly, in higher education.

True, Hiers's chalkboard message did not illuminate his reasons for disagreeing with the flyer. Hiers did not, for example, articulate his belief that "many of the statements that the fl[y]er condemns as 'microaggressions' can (and should) be interpreted in a benign or positive manner" and that "the fl[y]ers teach people to focus on the worse possible interpretation of the statement, to disregard the speaker's intent, and to impute a discriminatory motive to others." Had he done so, there would be little doubt—if any—that his speech would be constitutionally protected. But taken in context, the result is the same: Hiers's speech reflected his protest of a topic (microaggressions) born from the present-day political correctness movement that has become an issue of contentious cultural debate.

The flyer itself, which Hiers effectively incorporated by reference into his message, supplies important content and context. It broadly defines microaggressions as "everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership." A microaggression, in other words, can be composed of non-threatening speech, deployed unintentionally, or the result of unconscious stereotypes or bias. The flyer contains examples of purported microaggressions that people—in particular, university faculty members—should avoid in the name of reducing the harm to marginalized groups. Statements such as "I believe the most qualified person should get the job" and "America is the land of opportunity" are cited as microaggressions promoting the "[m]yth of [m]eritocracy." And the phrase "America is a melting pot" is listed as a microaggression because of its "[c]olor [b]lindness."

Hiers responded by criticizing the concept of microaggressions promoted by the flyer. That he did so by jokingly referring to the flyer as "garbage" does not deprive his speech of the First Amendment's protection. See Rankin v. McPherson (1987) (holding that a hyperbole about assassinating the President during a conversation about the President's policies addressed a matter of public concern). After all, humor and satire are time-tested methods of commenting on a matter of political or social concern…. And while Hiers's chalkboard message was not detailed or well-reasoned, it unequivocally advanced his viewpoint on microaggressions. In Hiers's words, the concept of microaggressions described by the flyer, is "garbage." See Snyder v. Phelps (2011) ("While these messages may fall short of refined social or political commentary, the issues they highlight … are matters of public import … [and t]he signs certainly convey [the speaker's] position on those issues[.]").

Arguing that Hiers's speech did not relate to a matter of public concern, the university officials characterize his message as "uncivil" and attempt to draw parallels between this case and those involving the use of profanity or sexually explicit comments in the classroom…. [But p]utting aside whatever one might think about his viewpoint, an objective reader would understand Hiers's criticism of microaggressions as a criticism concerning a hotly contested cultural issue in this country. Moreover, Hiers's method of communicating his criticism did not involve the kind of features that would place it outside the First Amendment's ordinary protection. For example, Hiers's message, while perhaps rude or even offensive, did not amount to "fighting words." Nor was Hiers's speech obscene as that term is understood. Rather, Hiers expressed the kind of pure speech to which the First Amendment provides strong protection.

The First Amendment protects "even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate." So while Schmidt, the other university officials, and some UNT professors may have taken great offense at Hiers's chalkboard message, that offensiveness is "irrelevant to the question whether it deals with a matter of public concern." To be sure, nothing that Hiers said could be more disturbing than a law-enforcement employee's expressed desire to see violence inflicted on the President of the United States. See Rankin (holding that such speech was constitutionally protected).

The university officials' reliance on Martin v. Parrish (5th Cir. 1986), only serves to underscore the flaws in their argument. In Martin, a university professor was terminated for telling his students while teaching that their attitude was "a bunch of bullshit" and that "if you don't like the way I teach this God damn course there is the door," among other profane phrases. Concluding that these "epithets did not address a matter of public concern," the Fifth Circuit explained that "surroundings and context are essential" when determining whether constitutional protection is afforded to indecent language. Taken in context, the court reasoned, the professor's profanity "constituted a deliberate, superfluous attack on a captive [student] audience with no academic purpose or justification."

Hiers's speech is meaningfully different from that in Martin in terms of both content and context. As to content, Hiers used no profane or vulgar language. When the Fifth Circuit said that schools could punish "lewd, indecent or offensive speech," it did not mean to include all speech that someone somewhere might find subjectively offensive. Otherwise, government restrictions would encompass nearly all forms of speech, and the First Amendment would be rendered a nullity in the public-employment context. And as to context, which is "essential," Hiers's speech did not take place in a classroom or in front of a captive audience of students. He spoke to his colleagues and supervisors in the faculty lounge, where professors regularly talk about political and social issues with one another, "and often with a heavy dose of banter." Put simply, Martin holds no sway here.

The same is true of Buchanan v. Alexander (5th Cir. 2019). There, the Fifth Circuit determined that the use of profanity and sexually explicit discussions about professors' and students' sex lives were not related to the education of college students training to be preschool and grade school teachers and did not touch on a matter of public concern. That's because, "in the college classroom context, speech that does not serve an academic purpose is not of public concern." Again, Hiers did not use profanity, speak about professors' or students' personal lives, or speak in the classroom context. So once more, the university officials are comparing apples to oranges.

Switching gears, the university officials point out that it's unclear from the complaint whether there was widespread debate on microaggressions at UNT when Hiers spoke on the subject. That may be true, but it doesn't change the outcome here…. Hiers's speech directly addressed a newsworthy social and cultural issue that continues to be an important and sensitive topic in public discourse, especially as it relates to colleges and universities across the country. In recent years, the concept of microaggressions has been vigorously debated by scholars, as well as the subject of congressional testimony. To suggest that speech on such a matter is not of public concern is to deny reality….

Together with content and context, the form of Hiers's criticism of microaggressions also weighs in his favor—though only slightly…. Hiers's speech was not made in public or visible to everyone in the larger university community. But neither was it made in private. Similar to the intra-office questionnaire in Connick v. Myers (1983), Hiers's criticism of microaggressions was displayed on a communal chalkboard in a space open to faculty, administrators, and possibly even doctoral graduate students. What's more, Hiers alleges that UNT professors regularly discussed all manner of topics, including political and social issues, in the faculty lounge…. [T]he chalkboard appears to have served as a sort of bulletin board for the UNT mathematics department. Thus, although Hiers did not sign his name to the chalkboard message, his speech could have triggered a more robust intra-office debate on the topic of microaggressions. After all, Hiers was responding to someone else's anonymous speech when he criticized the flyer, and his anonymity did not last long. Under these circumstances, the form factor weighs slightly in favor of finding that Hiers's speech touched on a matter of public concern. In sum, the Court concludes that the content, context, and form of Hiers's chalkboard message, as revealed by the whole record, show that his speech touched on a matter of public concern….

Having determined that Hiers spoke on a matter of public concern, the next step for the Court is to balance his interest in speaking against "the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees."

In balancing these interests, courts consider "whether the statement impairs discipline by superiors or harmony among co-workers, has a detrimental impact on close working relationships for which personal loyalty and confidence are necessary, or impedes the performance of the speaker's duties or interferes with the regular operation of the enterprise." It is unnecessary "for an employer to allow events to unfold to the extent that the disruption of the office and the destruction of working relationships is manifest before taking action." But there must be some "reasonable predictions" or "danger" of disruption.

Here, the university officials have not addressed the Pickering balancing test, effectively conceding the point at this early stage. They have not asserted any interest in restricting the speech at issue—let alone argued that any such interest outweighs Hiers's interest in speaking…. [B]ecause one side of the scale sits empty, the Pickering balance strongly favors Hiers. The Court thus concludes that Hiers plausibly alleged that his interest in speaking on the topic of microaggressions outweighed UNT's interests—whatever those might be—in restricting his speech. Hiers's retaliation claim passes step two of the Pickering balance….

"Preserving the 'freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think' is both an inherent good, and an abiding goal of our democracy." The university officials allegedly flouted that core principle of the First Amendment when they discontinued Hiers's employment because of his speech. Accepting the allegations as true, the Court concludes that Hiers plausibly alleged that the university officials violated his right to freedom of speech….

The court also concluded that, to the extent the decision not to rehire Hiers was motivated by his refusal to apologize, that violated Hiers' right not to be compelled to speak:

Hiers alleges that the university officials … pressured him to apologize for expressing his views on microaggressions. Based on the complaint and its attachments, particularly Schmidt's email detailing the reasons for Hiers's termination, it is not clear what this apology would have entailed. On the one hand, Hiers may have been pressured to apologize for the way he delivered his message—attacking a colleague's belief in a flippant manner—rather than for the viewpoint he expressed.

But Hiers's allegations, on the other hand, also give rise to a plausible inference that this apology would have involved him recanting his contrary beliefs about microaggressions. After all, Hiers alleges that the university officials terminated him not only because he refused to apologize for his speech but also because he declined to attend additional diversity training. Taking these allegations as true and viewing them in the light most favorable to Hiers, it is plausible that the university officials unconstitutionally punished Hiers for refusing to affirm a view—the concept of microaggressions—with which he disagrees…. "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein." … [And] Hiers has plausibly alleged that the university officials discontinued his employment—that is, punished him—because he did not express honest regret about his views and speech on microaggressions….

[A]ccording to the complaint, Schmidt … pressured [Hiers] to apologize for expressing his views on microaggressions. The university officials then terminated Hiers's employment, according to the complaint, because he stood by his criticism of microaggressions, did not apologize for his message, and declined to participate in extra diversity training. These allegations—again, taken as true and viewed in the light most favorable to Hiers—support a plausible inference of compulsion.

Finally, the university officials argue that Hiers "was never required to publicly announce his support for the concept of microaggressions or to otherwise publicly apologize for his conduct." But they cite no authority, and the Court has found none, indicating that it matters whether the government seeks to compel speech in public or in private. To the contrary, precedent establishes that the government violates the First Amendment when it tries to compel public employees to affirm beliefs with which they disagree. Period.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Gag me with a spoon. Gag Hiers with your smug wokeness. I hope the court gags you.

His letter ends worse:

"Finally, I was disappointed at your response during our conversation. Everyone makes mistakes, and I'm all for forgiveness if actions are followed by honest regret. But you very much defended your actions, and stated clearly that you are not interested in any kind of diversity training".

Honest disagreement is a fireable offense.

Firing is a macroaggression. Are adjuncts at will employees. Would a lawyer have advised the letter to end at, we cannot renew your contract, period?

Adjuncts are professional employment contract/term employees, per semester. Meaning that what the school could do solely from an employment law perspective is remove the teacher from the class, pay off the contract for the term and not rehire.

I hate to say this. Chairman should have consulted a lawyer about the letter.

You might have a point in some contexts, but a government employer firing an employee for views they don't like when they are using an open forum for expression probably isn't one of them. After all the microaggressions flyer was also unofficial opinion, is only one flavor of speech sanctioned? That's not going to pass muster.

And it's very likely the university also has guarantees of academic freedom and expression in it's university and faculty handbook.

Where the administrator screwed up is admitting that the adjunct was being terminated for wrong speak.

I was only the questions as to whether adjuncts are at will. Certainly if you refuse to renew a term limited professional employment contract for illegal reasons that could get you into trouble. Years ago my college got into trouble for not renewing an administrators long term employment contract because the employee was too old (that President didn't last long).

And as an attorney, let me note, I should have put in the qualifier *arguably* before "too old."

The President was too careless with his words when it came to discussing employment matters.

https://law.justia.com/cases/new-jersey/supreme-court/2010/a-13-09-opn.html

Was Nini an effective teacher? It was irrational to fire her for age.

A nurse's shift was associated with a high death rate in the ICU. He was fired. The firing employer refused to reveal the reason for the firing to the hiring employer. Thus the most prolific serial murderer was shielded by fear of litigation. He was arrested only after a police detective found the pattern. The employers were afraid of being sued.

She was an administrator not a teacher. But that's the thing: My opinion only: I doubt she was let go because of her age. If you read the opinion carefully you see there was an earlier acting President and the Board of Trustees who informed her they wanted her to go without saying anything about her age. They just wanted her gone for other reasons.

The new President then sticks his foot in his mouth with comments about her and other people's age.

The older acting President was an attorney (and long time administrator at the college). Dr. Rose was not. Dr. Rose had his talents (he hired me after all); but knowledge of the legal aspects of running a college was not his strong point. (Ultimately he got terminated for cause because he didn't know how to properly comply with the financial rules.)

https://pragertopia.com/2021/09/13/dennis-prager-20210913-3-woke-military/

During the interview, Col. Lohmeier said that the reason given for his dismissal was that he was being "political" -- by writing a book (and speaking out) against (leftist) politics in the military.

Anything and everything we say & do serves the goal of "fighting discrimination" and promoting "diversity / equity / inclusion." As such, it is simply common sense, something that all decent people should agree with, and not at all political.

Anyone objecting to anything we say & do seeks to subvert these (common-sense, non-political) goals. By doing so, they are being political and, if the setting is supposed to be apolitical -- such as the military or a math department at a public university -- can be dismissed accordingly. (Otherwise, they can be "cancelled" for not being a decent person.)

All three of you express opinions in a fres society. One wants to use the power of the state to hurt you.

Woke is religion. It contains an orthodoxy thst many religions used, that to even question their tenets is a sin, and must be punished. And, like any religion, evil or otherwise. Well, evil, religion, it seeks government power to precisely enforce its will on unwilling participants.

In meme terms, religions and political parties are memeplexes seeking the brass ring of power.

Then the meme need no longer spread by the mechanism of people deciding it is a good idea to adopt.

Rather, it can be forced.

The purpose of speech is to ultimately affect the behavior of others. But you can also do that by force.

(As an aside, that you and your memes are so gosh darned right, it is proper to use force, is itself a meme these giant memeplexes adopt to aid altering the host coputational units' (humans') behavior.)

And what if he just did not like trash left in his classroom? First Amendment violation?

"Microaggression" is the cry of those who are too weak to handle real life.

That idiocy makes very much sense? Are you fucking kidding me?

His idiocy in agreeing with the students on this is the biggest microaggression in this story. Sometimes you wonder if it’s simply time to shut down the university system because it’s doing more harm than good.

Stop with the letters and with the lawsuits. Mandamus the Non-Profit Office of the IRS to rescind the non-profit status. Do that one time, woke is over all over the country.

Uh, revoke the non-profit status of... the Texas state government?

Make the school choose between woke and $20 million a year.

https://990s.foundationcenter.org/990_pdf_archive/237/237232618/237232618_201808_990.pdf

You may very well be right (re: universities doing more harm than good), but I'd shut down public colleges / universities on principle -- providing higher education is not a proper function of government.

Just the tip of the iceberg. Trillions of tax dollars are poured straight into the operating accounts of every "private" university in the form of federal "student loans."

Woke used to mean you were hip to the bullshit. Now it means that bullshit is the only thing you believe.

Its become a mental health issue.

“ I believe the most qualified person should get the job” is a microagression?

Microagression: A small aggression against someone's large sense of entitlement.

"I deserve that college slot more than you do!"

"I deserve that job more than you do!"

"I deserve that house more than you do!"

Etc.

Yes, because merit supposedly comes from privilege. Immigrants rebut all woke. They come with nothing from a village with huts. They do the standard USA thing. They end up at the top, over and over, without fail. That includes immigrants with the darkest skin on earth.

Good point! Like I said, I'm glad I didn't mute you.

(And no wonder Queen Amalthea hates you!)

It's called a microaggression because you need to be a special kind of tool to detect the aggression in the statement.

"It's called a microaggression because you need to be a special kind of tool to detect the aggression in the statement."

These aggressions are invisible to all, except highly paid consultants, or the myriad of diversity executives on a campus

Depends on the context.

As a response to the question, "How should we decide whom to hire?" No, it's hard to see the "microaggression" there.

As a response to the statement, "I intend to nominate the Court's first Black woman justice for the open spot"? The intent is clearer there.

Blatantly declaring a racist, sexist criterion like that is more than a mere microaggression. It's a flat declaration of war on American culture and law.

God, the fucking morons here.

Leftists usually (always?) suffer from a superiority complex.

And what do you think your own comment evinces?

For sure, but more significantly I think they suffer from feelings of inferiority. While he was a bad and insane person, Ted K had a funny way of putting a few things. "The leftist’s feelings of inferiority run so deep that he cannot tolerate any classification of some things as successful or superior and other things as failed or inferior. "

If it's one thing that's incredibly consistent about tards like Simon, it's that they have a burning resentment for those who they think are above them, and utter contempt for those who they think are below them on the class scale. And it's been that way for the last 100-odd years.

Hi, Simon. Are you asking to be cancelled? Zero tolerance for woke. All woke are servants of the Chinese Commie Party, and enemies of our nation.

Imagine what we think about people who think that critical responses to an explicitly race- and sex-based decision are good examples of microaggressions.

Takes abound: "It's a flat declaration of war on American culture and law."

The irony is that your statement can be read another way, which is that it's the complaint of a racist bemoaning the end of white supremacy, which he implicitly acknowledges to be intrinsic to "American culture and law."

How does the saying go? "Amazing how pointing out racism is the real racism", or something like that?

Criticizing a racist, sexist decision is not a microaggression. Full stop. Your personal attacks don't make you right, they just show that you are an asshole.

My, such a snowflake.

I don't think I engaged in any personal attack. I simply pointed out that your statement was susceptible to two interpretations.

You'd described Biden's stated commitment to naming a Black woman justice to the Court as a "flat declaration of war on American culture and law." It's not at all clear how this can be literally true, because the commitment was a campaign promise approved by American voters and is not barred by any law, and is not even all that atypical historically. It was, in other words, a hyperbolic and incoherent statement.

But I understood your meaning - you were saying something about how "American culture and law" is inconsistent with stated racial/gender preferences when handing out jobs and appointments. But this again is a little hard to square with our longstanding (if generally implicit) commitment to appointing white men to these spots. So your statement can be re-read, and in fact read more coherently, to be less of a condemnation of a failure to abide by a post-racial ideal, than as a cynical attempt to invoke putatively "post-racial" ideals in order to continue a longstanding white-supremacist order. Read as such, this statement also tellingly acknowledges how threatening naming a "Black woman justice" would be for that order.

You view that as a "personal attack," but my response to this complaint is - man the fuck up. If you're not a racist, then some pseudonymous interlocutor online suggesting otherwise is no threat to you. Live your life and don't worry about it. But I don't owe you a single benefit of the doubt.

Literally your first comment in this thread was "God, the fucking morons here." -- and nothing else. And you don't think that's a personal attack?

No, you just don't think. The rest of your comments have been verbal diarrhea.

Well, I had tried to be succinct, at first, you fucking moron.

I don't think

That much is obvious.

Simon. All woke are servants of the Chinese Commie Party. Zero tolerance for woke.

God, the fucking morons here.

And by "here" you mean whatever room you're in at the moment.

As a response to the question, "How should we decide whom to hire?"

Clearly the only acceptable answer is a black woman. If lesser, even better.

That hiring of a black woman is ablist and discriminates against the 540 ways to love.

Anything that might disrupt the feelings of the special people is a microaggression. The special people have a right to never experience negative feelings and you have a moral and professional duty to assure that they don’t.

.And everyone else besides the special people can go fuck themselves and their feelings because they’re all second and third class people.

Didn’t you learn that yet?

welcome to a society that is so decadent and has no external enemies has to create internal ones

We certainly have an implacable enemy, the oligarchsof the Chinese Commie Party. The woke are their servants.

Commie makes China weaker. Imagine their strength if they went 100% capitalist. Commie is good over there, but zero tolerance for Commie here.

Or to a society that is advancing to the point that stale right-wingers just can’t stand all of this damned reason, progress, science, modernity, and diversity, so they start establishing laws in backward states that remove books from libraries and gag those who want to acknowledge that gays exist.

At this white, male, right-wing blog, the focus reflects the polemical, partisan, disaffected desire to lather a collection of intolerant, ignorant conservatives.

Arthur really wants to talk to kindergarteners about sex.

So the "grooming" line is about the best we can expect of Republican politicians these days. It's all trolling for them, and if they can get their base lathered up by lying about what they're doing, it's all to the good. Force their opponents to get caught up in having to do the work of debunking the lies, a message that gets hopelessly muddled in our media environment. While talking heads on FoxNews keep their audience entertained by calling Democrats "groomers."

What I don't understand is why any individual non-politician would take that line up. It immediately marks you out as a cynical liar, completely disinterested in engaging in any debate like a rational adult. You know that it's not about talking to kindergartners about sex, you know that no Democrats (or ALK) want to have "age-inappropriate" discussions with kindergartners about sex. Yet you can't help yourself. You repeat the lie just as though you were a political operative yourself. Why?

Are you for real? Or just some over the top parody like "the Rev"?

I could ask the same about you.

Stop acting like groomers and you won't get called groomers, you sex pest.

But the law in Florida merely says that discussion about sexual orientation can't be part of the curriculum for children 8 and under,

What's wrong with that?

Anyone who insists it needs to be part of the curriculum or classroom discussion at that age probably is a groomer. Age inappropriate discussions about sex with young children is grooming behavior.

You can have an age-appropriate discussion with kids in third grade and younger about sexual orientation and gender identity without uttering a single word about sex, and having those discussions with those children in no real sense constitutes "grooming."

If it were grooming, you'd have to also claim that every same-sex couple with a young child, every trans parent with a young child, every LGBT parent of a child who has friends over, etc., is likely in some sense "grooming" those children. Is that your claim?

Again, no one wants to have "age inappropriate" or sexually explicit discussions with kids. To claim that people opposing the law are for such discussions just because they are against the law is arguing in bad faith, and I think you understand that.

If it were grooming, you'd have to also claim that every same-sex couple with a young child, every trans parent with a young child, every LGBT parent of a child who has friends over, etc., is likely in some sense "grooming" those children.

No, he wouldn't have to make that claim, nor would it logically follow from the claim he is making. Either you know that and are a dishonest asshole, or you're far dumber than you think you are.

Embrace the heading power of "and"!

Simon. You need to be forced to stand up in Kindergarten. Publicly confess that you have white privilege. You need to confess your white privilege caused the underperformance of diverses.

He was on your side with that statement.

OK, Boomer. STFU until you post your resignation letter and your interviews of diverses for your job. Woke talk from an old white male supremacist is garbage. Only woke action has any meaning.

External enemies seeded many of the cultural problems we face now.

Here is a relevant article:

Microaggressions, Questionable Science, and Free Speech by Edward Cantu and Lee Jussim. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3822628

"The topic of microaggressions is hot currently. Diversity administrators regularly propagate lists of alleged microaggressions and express confidence that listed items reflect what some psychologists claim they do: racism that is, at the very least, unconscious in the mind of the speaker. Legal academics are increasingly leveraging microaggression research in theorizing law and proposing legal change. But how scientifically legitimate are claims by some psychologists about what acts constitute microaggressions? The authors—one a law professor, the other a psychologist—argue that the answer is “not much.” In this article, the authors dissect the studies, and critique the claims, of microaggression researchers. They then explore the ideological glue that seems to hold the current microaggression construct together, and that best explains its propagative success. They close by warning of the socially caustic and legally pernicious effects the current microaggression construct can cause if academics, administrators, and the broader culture continue to subscribe to it without healthy skepticism."

Thanks Scott. Interesting read. I hope quite a few of the Conspirators check this out.

The proper response to any accusation of microaggression is an ass kicking. The accuser is a denier with a Chinese Commie agenda, and does not argue in good faith.

Who cares? If you get genuinely upset that I say “hire the most qualified person” or “America is the land of opportunity”, that is on you: I am still saying it.

The point was he was fired despite the fact the science agreed with him.

To be fair, the correct term is "trash", not "garbage".

“Rubbish” also works, especially if you’re a Brit.

Hey, that's paper. It belongs in the recycling.

From an employment law perspective, does Hiers even have a leg to stand on? Looks doubtful....he is an 'at will' employee.

If his employer was a private company that made no representation about academic freedoms, you might have a point.

Adjunct, no tenure. What leg does he really have to stand on in terms of employment law, Michael P?

The employer admitted he would have been hired but for the microaggression against microaggression. The boss should have said "your services are no longer required" to reduce liability.

That is where my head is, also. Just say, "Adios" and be done with it.

Sure, the employer might have acted differently, and in doing so made it hard to prove that they violated Hiers's 1A rights. But they were very explicit that their motives were to do so.

Why would the boss care about liability? This was a great chance to signal how woke he is.

Accidentally flagged your comment and don’t know how to unflag it. Ooops. Anyway, maybe the boss is actually a genius who has figured out a way to be seen to be on the side of the microagression types while still rehiring a guy who appears to have been a capable math teacher.

Could have, yes... but were they then also going to lie under oath when the deposition came asking why the person was fired?

As the court here explained, this speech was not part of his job duties (Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006)). As it continued to explain, the speech was on a matter of public concern (Connick v. Myers (1982)). And the government's concern as an employer is at least arguably outweighed by the employee's interest in speaking freely (Pickering v. Board of Education (1968) and Connick again).

This all means the First Amendment protects the employee's speech, even against the government as an employer. The excerpt above walks through this three part test, which is what the Supreme Court has said is the proper framework.

But even if that were not enough, this employer made the same kind of representation that many universities do about its dedication to academic freedom and open exchange of ideas. The employee relief on those representations, to his detriment at the hands of the university.

That is the level of legal analysis to be expected at a white, male, conservative blog these days.

Wow. What a bigot.

Arthur, people of any color or sex are capable of producing this type of clear, concise, and correct analysis.

C-XY,

Heirs claim is that he was fired for an illegal reason. If that is the case, at-will status does not protect the university

Ha! Good luck with that one = fired for 'illegal' reason

It helps when the employer lays out in writing why they fired you.

The First Amendment apparently protects your right, as a public employee, to be a dick at work, provided it's about a high profile issue.

Yup. That's why the guy who posted the idiotic microaggression poster should not be punished.

If you're trying to bait me into defending the pamphlets, it's not going to work. I also find the whole "woke" discourse tiresome.

I am, however, able to navigate my issues with the DEI fad in a way that hasn't negatively impacted my career. The adjunct was behaving like a child, rebelling because he felt powerless to do anything real about the slightly annoying thing he lets live rent-free in his head.

"rent-free in his head"? He was complaining about pamphlets in the faculty lounge, not something in his head. Are you trying to rival Sarcastr0 for blatantly stupid lies about plain facts?

You don't think the pamphlets just gave him an opportunity to spout off about something that has been irritating him for a while? Like the pamphlets were his first exposure to the idea of "microaggressions," and he responded in a completely reasonable way? And his obstinance when it became an HR problem just came out of nowhere?

I note that you didn't even remotely try to argue that "what all parties agree was intended as a joke" is an example of anything living rent-free in the plaintiff's head.

His response was a completely reasonable one, and the department chair created a problem to try to bulldoze someone who disagrees with leftist orthodoxy. This is a prime example of how wokeism is a religion that persecutes heretics.

I note that you didn't even remotely try to argue that "what all parties agree was intended as a joke" is an example of anything living rent-free in the plaintiff's head.

It seems clear from the way the "joke" was handled, the way Hiers "defended" making the joke, and the court's constitutional analysis, that it was a "joke" expressing a deeply-felt point of view. You're grasping at straws here.

"Judge Sean Jordan"

Good judge.

A clinger from our southern backwaters. In the long run, just another disaffected culture war casualty. A loser in modern America.

And yet the state of Florida wants to regulate speech by private companies and the Republicans in that state are . . . .

Why, because they agree that government should regulate and ban speech with which they do not agree. The Constitution protects only 'correct speech' in their minds.

You won't read about that much at The Volokh Conspiracy, the Official Legal Blog of White, Male, Right-Wing Grievance.

In case anyone is ignorant about what is going on with Ron DeSantis, aka Vladimir, in the state here it is

"a bill backed by Florida governor Ron DeSantis that would prohibit public schools and private businesses from inflicting “discomfort” on white people during lessons or training about discrimination . . . "

Yes, government is telling private businesses what they can say. Conservative???

Yes, because having the KKK teach schools or teach required training for employment is a great idea. Really, it is.

Or fighting fire with fire?

That just looks like ancient situational ethics, though.

Are you this upset about hostile environment rules in federal law?

Reads to me like you're hallucinating.... As usual.

That's been the law for a while Sidney, creating a hostile work or education environment of the basis of race or sex was established as subject to government sanctions and private lawsuits decades ago.

Hopefully nobody left this paper, "Teaching About Racial Equity in Introductory Physics Courses" laying around in there.

How would you even do that?

A white man weighing 90 kg is fired from a cannon at a velocity of 1000 m/s and at an angle of 50.2 degrees. How much time passes before he hits the ground?

Assume a black man is fired from the same cannon under the same conditions.

Is the black man in the air for

a) less time

b) more time

c) the same amount of time

You explicitly assigned a weight to the white guy but not to the black guy. Not bothering to state the black guy's weight implicitly says he is not as important as the white guy. Also, you put the white guy first, putting the black guy at the end of the line.

1. "Under the same conditions" is meant to imply that the black guy weighs the same, although it doesn't matter how much they weigh.

2. "Also, you put the white guy first, putting the black guy at the end of the line."

I've watched enough movies with enough black guys to know that shooting the black guy out of the cannon first is a microaggression.

TwelveInchPianist: Just to make sure there's no misunderstanding. My reply was intended as a joke.

". . . although it doesn't matter how much they weigh."

Am I mistaken about the reasoning? I reason that for a human of a given caliber, a less massive human projectile, fired on any trajectory, will more quickly lose velocity because of air resistance. On any upward trajectory, that would affect the trajectory, resulting in a lower maximum altitude, a shorter flight, and a shorter flight time for the less massive projectile.

It would be more complicated if you had not fixed the muzzle velocity, but instead had given the less massive projectile a higher muzzle velocity, as would typically happen with the same propulsive charge.

It would have been simpler if you had not fired the projectile people upward, but instead horizontally over a level plane. In that case the flight time would be nearly the same, regardless of horizontal deceleration due to air resistance, because the distance to fall would remain the same for each. "Nearly," because downward velocity due to gravity would vary slightly according to differing effects due to air resistance.

Had you fired both horizontally, over a downward-sloping surface, or over an upward sloping surface, there would once again be differences in flight time caused by a difference in deceleration due to air resistance.

Had you fired both parallel to either a downward-sloping surface, or parallel to an upward sloping surface, there would be a difference in flight time caused by a difference in deceleration of a less-massive projectile compared to a more-massive projectile, but the flight times would be different than in the foregoing examples. Of course, a difference in flight times would occur even if the shots were made straight up, or straight down, but the differences in time would vary at different angles from vertical.

Finally, even if both projectiles are the same caliber and weight, do not expect the flight times to match if you fire parallel to a level surface, compared to the result you get firing either up-slope or down-slope. In such sloped-surface examples, expect an intuitive paradox, with both up-slope and down-slope shots registering high at any given distance from the muzzle, compared to results from projectiles fired parallel to a horizontal surface.

I may be mistaken on any or all of those. I am most doubtful of the last example. I invite ballistic hot-shots to correct me.

So the black guy wanted to be fired out of the cannon before the White guy?

I'm pretty sure all my black friends would be fine waiting to be last.

But since the hypothetical was 1000m/s

1000 m/s is 3600 kilometers per hour, I'm guessing you are just going to get a red mist with some bone fragments spread out over about 10 kilometers, and are going to have a hard time telling any difference between the black guy and the white guy in accessing the results.

The answer is...very slightly more time.

As the white man is shot into the air, his skin reflects the sunlight (or moon/starlight at night). That create a very slight force downwards towards the sky.

The black man absorbs the sunlight, thus the force that would go into a reflection isn't forcing the black man down. In addition, the very slight heat generated by the black man absorbing the sunlight, slightly increases the updraft on the man.

To be fair, being shot out of a cannon at 1000 m/s can be a little disorienting.

You could at least read the abstract of the article you've linked.

What would be the point? It's the kind of abstract, and article, that leads deans to say things like "What you've just written is one of the most insanely idiotic things I have ever read. At no point in your rambling, incoherent blather were you even close to anything that could be considered a rational thought. Everyone in this school is now dumber for having read it. I award you no points, and may God have mercy on your soul."

What would be the point?

Well, among other things, it might lead one to fashioning a critique of the piece that is actually relevant. Instead it's just a bunch of chuckleheads making jokes about shooting people from cannons. Or, in your case, feigning to have read the abstract, so as to dismiss it out of hand without comment.

Nobody needs to read a damn thing to realize that "Teaching About Racial Equity in Introductory Physics Courses" would be hijacking the course. It is introductory physics, not introductory woke pop-sociology. As a result, the abstract is intentionally obscure to try to avoid revealing the idiocy of the proposal.

If they had an actual point, they might have written "Addressing Racial Inequity in Introductory Physics Courses", but they did not.

Nobody needs to read a damn thing to realize that "Teaching About Racial Equity in Introductory Physics Courses" would be hijacking the course.

Would it? It seems to me that, if I were taking an introductory class in a field where, for whatever reason, people like me were underrepresented in the actual profession, the most logical time and place to address that phenomenon and how to navigate it would be the introductory class.

The only reason you're arguing it is "hijacking" the course is that you don't view the phenomenon of underrepresentation as needing to be addressed. And I get it - you're one of those people who thinks the best way to address racism is to pretend it doesn't exist. But the article may make a helpful point for people who don't live in a fantasy land.

The reason I say it would be "hijacking" the course is because the course is supposed to be on introductory physics, not on introductory "how to be a totalitarian, identitarian moron".

If somebody wants to teach a course on the latter, there are perfectly good departments for that. The science department is not one.

The reason I say it would be "hijacking" the course is because the course is supposed to be on introductory physics, not on introductory "how to be a totalitarian, identitarian moron".

I am not really sure how you are getting to that from the abstract.

Probably because the person who wrote it assumes black people can't do math that's any more complex than 5th-grade algebra.

I'm going to go out on a limb here and make the assumption that the Black guy didn't get lost in the way to the Black studies department,and maybe he picked a physics course because it was so dispassionately un-racial.

Maybe he's thinking isn't there anywhere I can go where people don't think I need special consideration as a black man?

Since none of you lazy assfaces can be bothered to follow a link:

Even after you have decided to tackle a problem like racial equity

Damn, it even starts off by begging the question. At least race pests like Saira Rao are honest that they hate white people, rather than trying to toss it within a rhetorical word salad.

Or better yet, let's not, and instead teach physics.

All the answers to every question are "shut up".

Crazytown.

The limitations of this case are worth noting. The District Court found in the professor’s favor not because he was acting as a university professor at the time, but specifically because he wasn’t. He wrote his comment in the faculty lounge, on his off time, a place off limits to ordinary students.

Thus his win was not based on any concept of academic freedom or any notion of the first amensment incorporating any special rights for university professors because their institutional role. Rather, it was based solely on his role as a government employee, and one not acting in any capacity that could be regarded as speaking on the government’s behalf. The opinion suggests, or at least opens the possibility, that if this had happened in a classroom, the outcome might be different.

The courts are supposed to avoid making new case law when it can be avoided. Take the win.

"Special rights"?